Love and Loss During a Pandemic

Wandering through the world of masked faces beyond my home feels like I am constantly being subjected to the “Reading The Mind in the Eyes” Test—a psychological task designed to test a person’s ability to accurately describe the emotional state of a person, based on only a photo of the eye region of their face.

When the cues from a smile, frown, or sarcastic smirk are obscured, it becomes incredibly difficult (not to mention anxiety-producing and exhausting) to understand the mental states of others during everyday interactions.

“Was that comment judgmental…or sarcastic?”

“Does that furrowed brow indicate confusion…or anger?”

The “Eyes Test,” as it’s sometimes called, has been used in psychological studies to measure the social abilities of individuals with autism spectrum disorder, a developmental condition in which difficulties in social behavior is one defining feature. By characterizing differences between patient populations and unaffected individuals, it becomes possible to test the effectiveness of various interventions on social function by measuring performance on the task before and after treatment.

There are currently no prescription drugs approved by the FDA to treat the social symptoms of autism. However, one experimental treatment option involves targeting the brain’s existing social circuitry, namely the oxytocin system. Oxytocin is a hormone produced by your brain and has traditionally been known for its role in childbirth, lactation, and maternal-infant bonding. In recent decades, researchers have found that oxytocin is also critical for the formation and maintenance of strong social bonds and for the social and cognitive abilities that allow us to interact with others in expected ways. Because of its role in modulating sociality, the oxytocin system has been implicated in the underlying neurobiology of autism.

The oxytocin system is the center of my research program as a new faculty member in the biology department at Utah State University. I am fascinated by the neurochemical mechanisms that govern complex social behavior. Oxytocin acts by binding to the oxytocin receptor in specific parts of our brain and activating those neural substrates, which ultimately leads to changes in behavior. Much of my research focuses on defining where oxytocin receptors are located in the brain, and one branch of my work seeks to determine if oxytocin receptors are expressed at different levels or in different locations in tissue specimens from individuals with psychiatric diagnoses like autism. My students and I study postmortem human brain tissue that was donated from individuals who had autism while they were alive, and we compare these specimens to tissue from typically developing donors. Recently, I found the first evidence for dysregulated levels of the oxytocin receptor in the autistic brain, which has important implications for our understanding of the biological basis for the social symptoms of autism.

Our own visual, social primate brain is being exhausted by the COVID-19 pandemic-related challenges of having to navigate our world with fewer facial clues to guide our interactions.

Beyond humans, my research also compares the distributions of oxytocin receptors across the brains of several animal species, using tissue acquired opportunistically after death. My research has found that the regions of the primate brain that express oxytocin receptors overlap with the circuits of the brain involved in visual processing and attention. If you compare this pattern with that of rodents’ brains, the regions highest in oxytocin receptors overlap primarily with the circuits that process olfactory signals from the nose. It appears these animals have evolved so that oxytocin is acting in brain regions that process incoming information from the sense organ primarily used to navigate their social environments: olfaction for rodents and vision for primates.

Our own visual, social primate brain is being exhausted by the COVID-19 pandemic-related challenges of having to navigate our world with fewer facial clues to guide our interactions. But that assumes that you’re regularly leaving the house. Many individuals have reduced their social activities and rarely interact with friends or individuals outside of their household. People across the globe are sheltering in place to the greatest extent possible to protect themselves or members of their family due to health conditions that put them at greater risk of death.

What impact is this social disconnection having on our brains? My first hypothesis is that the oxytocin system is being under-activated. In humans, oxytocin is released by different kinds of social stimuli, including eye contact, hugging, skin contact, and other forms of physical touch—the types of close interactions that many people have reduced or eliminated in their daily lives during the pandemic. Oxytocin has been shown to interact with two important neurotransmitter systems of the brain—dopamine and serotonin—that have strong modulatory effects on our mood.

But close physical interactions that release oxytocin in our brains aren’t the only social connections that this pandemic has diminished. One particularly painful challenge is the lack of social connection during major life events, like celebrations for births and weddings, but also shared sorrow after the death of loved one. As disappointing as it may be to limit a celebration, marriage ceremonies can proceed with small numbers of attendees, and wedding receptions can be postponed. But it is devastating to have to postpone a funeral and delay the gathering of grieving loved ones in order to prevent disease spread during a pandemic.

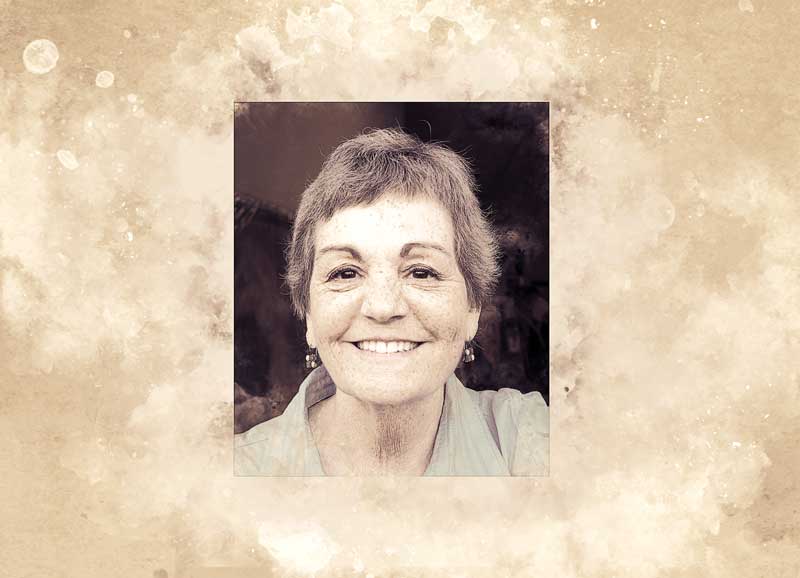

Everywhere Nancy went, she made a friend, often several, who frequently became dear friends for life, Dr. Sara Freeman says of her mother. “We will all forever miss her smile, the sound of her laughter, her caring and generous spirit, and the way she lit up every space she entered.”

Unfortunately, I have experienced this difficult and painful decision firsthand. On May 2, my mom died after a 5.5-year battle with breast cancer. She and my dad, as well as my brother and sister-in-law, live in Atlanta, Georgia, where I was born and raised. So when my mom’s health started to decline rapidly at the end of April, my husband and I packed our bags, put our 6-month old puppy in the car, and hit the road for a 3-day journey to the South. We opted to drive, because getting on a plane while COVID-19 was rapidly sweeping through American cities did not feel like a smart decision, especially given my mother’s immunocompromised state. But a sharp decline in her health resulted in a detour to the Denver airport, and I took a one-way, nonstop flight to Atlanta to get there as fast as I could.

But I didn’t make it in time. I missed her by only a couple of hours. Thankfully, my mom died at home in bed, which brought everyone peace and comfort, especially given the alternative of being alone in the ICU of a hospital during a pandemic. Still, it was the most painful experience I have ever endured, made worse by the fact that our family was then tasked with the decision of when to hold a memorial service to celebrate her life with her friends and family across the country. After deliberating for weeks, we postponed the service somewhat indefinitely and prioritized the safety of her extensive network of family and friends, even though it meant delaying the support, sympathy, healing, and closure that would come from mourning her death side-by-side. Sharing hugs, tears, stories, laughter, and meals in-person together will just have to wait a bit longer.

I know that my family and I are not alone in this painful period of waiting. Over 267,000 Americans have died from COVID-19, leaving multitudes more in mourning. And that doesn’t take into account the deaths this year from cancer, accidents, heart disease, or any of the other leading causes of death in our country. So while this pandemic has disrupted many aspects of our daily lives, the toll on our ability to appropriately mourn, in the opinion of this social neuroscientist, is likely the most damaging of all of the impacts of this pandemic.

My husband wisely reminds me during my lowest points, that the depth of my grief is a direct reflection of the intensity of the love that my mother and I shared. When I’m struggling, this view helps me to flip the narrative from something inexplicably sad to something incredible. And it also brings me perspective when thinking of my research on the neurobiology of strong, social attachment relationships. My work may focus on the biological forces involved in the formation and maintenance of social bonds, but there is certainly a biological impact of the loss of these social bonds as well.

With vaccine options in sight, eventually, those of us who are grieving will be able to safely gather in large numbers and to hug one another, laugh and cry together, share memories, and resume our lives. In the meantime, for those of you who can, call your mom and tell her you love her. It just may give her the burst of oxytocin she needs to get through the day.

By Dr. Sara Freeman

Dr. Sara Freeman is an assistant professor of biology at Utah State University. She studies the neurobiology of strong social bonds.