Uniting to Save Saline Lakes

For centuries, large saline lakes in Utah and Iran have served as feeding grounds for millions of birds. And lately, the lakes are disappearing.

Dust from the drying lakebeds threatens the health of millions of people nearby. The remaining water is saltier and less hospitable to life — potentially killing off once robust Artemia (brine shrimp) populations. Fewer birds and visitors flock to its shores.

Lake Urmia in Iran may be halfway across the world, but its challenges are both a cautionary tale and a playbook for what Utah might do to restore its own Great Salt Lake, which has dropped to its lowest level since recordkeeping began more than a century ago. A collaboration between Iranian researchers and Utah State University scientists may create a blueprint for advancing the health of other desiccated saline lakes. But it’s not simple.

“These aren’t issues that are going to be solved in one journal article, or in a month, or a year,” says David Rosenberg, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at USU and a water modeling expert. “These are long-term efforts. That is the kind of approach that our countries need to take if we are going to tackle these really complicated, complex problems that couple humans and nature.”

Lake Urmia and Great Salt Lake are sister lakes. They have similar latitudes, similar lake depths, and millions of people living nearby, he explains.

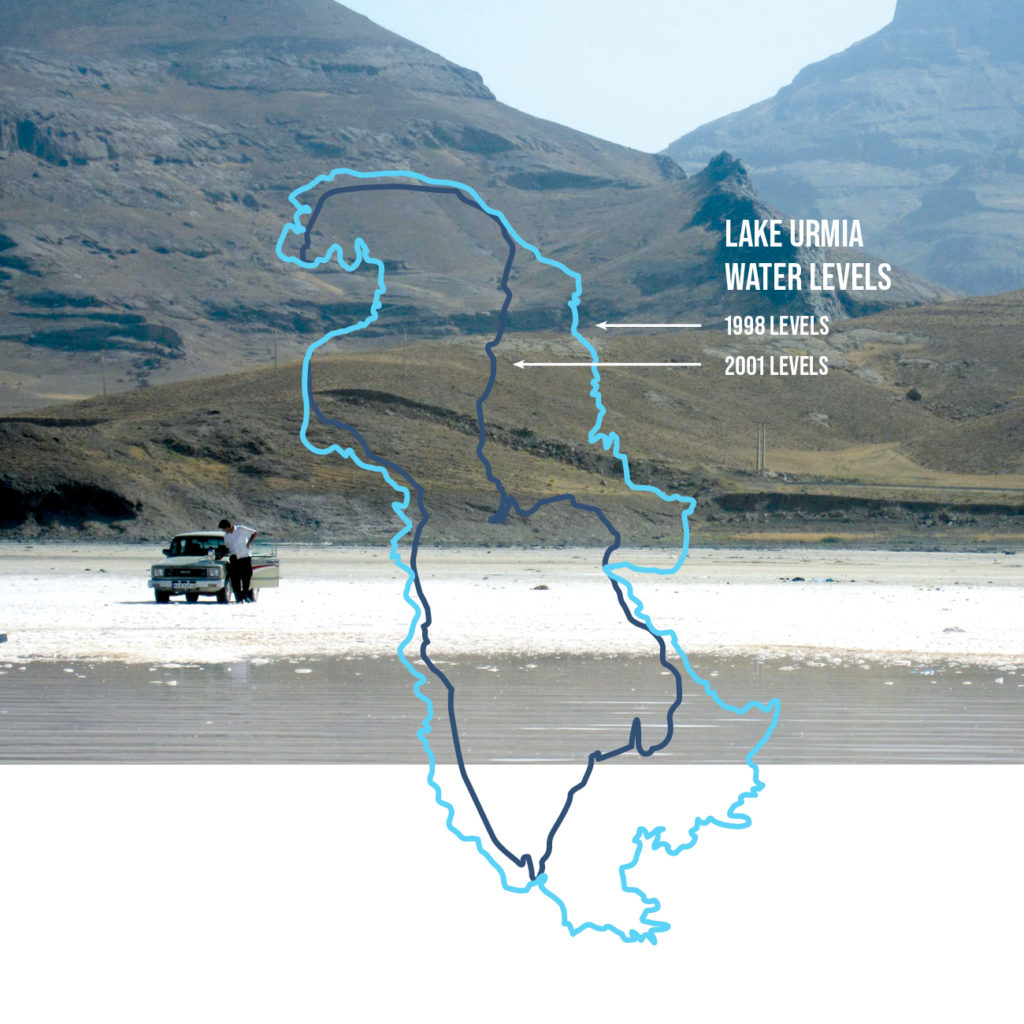

The lakes also have similar problems — namely, the upstream diversion of water. Since the 1970s, Iran has erected dozens of reservoirs, dammed rivers, and grown its agricultural sector in the region, ultimately starving Lake Urmia of inflow. Thousands of illegal wells have further depleted the water. The lake level plummeted in the mid-90s and has never recovered.

In 2013, the Iranian government funded the Urmia Lake Restoration Program (ULRP) with about $1 billion and set a target level of 1274.1 meters. Initially, the plan called for curbing agricultural expansion and reducing water use by 40%. The idea was to reduce salinity to preserve Artemia populations, which are an important food source for flamingos and other birds.

However, unknowns can stymy good intentions. The USU-Iranian research team found that the proposed lake level of 1274.1 meters may not sufficiently lower salinity and preserve the ecological benefits of the lake. Last summer, they published their findings in the open-source Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies to encourage greater cooperation between scientists and increase transparency.

“We are suggesting that management is a much more dynamic process,” Rosenberg explains. “It is not just the lake magically rises to 1274.1 meters and we just go home; all the problems are solved.”

Despite record precipitation in 2018-19, which replenished the lake for a spell, the lake’s future is hazy. In July 2020, 45% of the lake had shrunk in area and dropped in volume by 85% from its historical maximum. Recreational tourism disappeared along with the water.

“It’s kilometers from the resorts to where the water is deep enough to boat,” Rosenberg says.

In 2018, Somayeh Sima, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Tarbiat Modares University in Iran, became the first visiting scholar funded by the Semnani Family Foundation to collaborate with USU researchers on Lake Urmia’s restoration. The team outlined eight restoration objectives such as improved water quality, ecology, economic benefits, and human health, and suggested to track how various objectives are met as the water level varies over time. They also identified significant problems with the restoration plan, particularly, the limited monitoring of the lake ecosystem.

“We’re at the tipping point,” said Sima, the paper’s lead author. “Every single step matters. We have to take action now. … Restoration is not an easy task. It is everyone’s responsibility, and we’ll need public support to make meaningful change.”

Upon her return to Iran, Sima shared the team’s findings with members of the country’s Department of Environment and Ministry of Energy. A second Iranian scholar, Marsoud Parsinejad, recently came to USU to continue the project. He, Rosenberg, and a team of eight USU and Iranian researchers synthesized 40 years of Lake Urmia data, including satellite imagery and field observations, to outline additional recommendations for lake recovery. The paper, published in August in the journal Science of the Total Environment, calls for monitoring undercounted water flows throughout the basin, working with farmers to shift to higher value crops that use less water, and expanding data-sharing capacities between stakeholders.

They cited an urgent need to determine and quantify unknowns such as the extent of illegal water use, lake evaporation, and the characterization of food webs, among emerging issues like drought intensification from climate change. A recommendation involves building public support for the effort. And that isn’t as easy as it may sound.

“The fundamental challenge is human behavior,” Rosenberg explains. “Essentially, it’s ‘how do you voluntarily get someone to conserve water?’ That’s like the key question. It’s true here in Utah, and in the Great Salt Lake, and it’s true in Iran.”

Ultimately, the scientists want to connect with the people on the ground.

“Our thinking on this is that we have to start on the bottom up, working with individual farmers and with individual canal companies, and demonstration projects,” Rosenberg says.

The reality of American and Iranian relations affects this work. The USU team will not be traveling to Lake Urmia anytime soon and obtaining visas for Iranian researchers can be tricky. Nevertheless, the USU-Iranian team has forged a path forward by collaborating over email, Zoom, and using shared data centers. It’s an important start.

“It’s an opportunity that USU could catapult on in future,” Rosenberg says. “A small group of professors collaborating with a small group of professors in Iran, we can do something bigger. We are building trust. And when you have trust, you can do a lot of great things.”

By Kristen Munson

To join or support this effort, contact David Rosenberg at David.Rosenberg@usu.edu