A Healing Ground

“The souls of my ancestors peer out from behind my mask of skin, and through my memories and efforts, they get to live again.” — Darren Parry

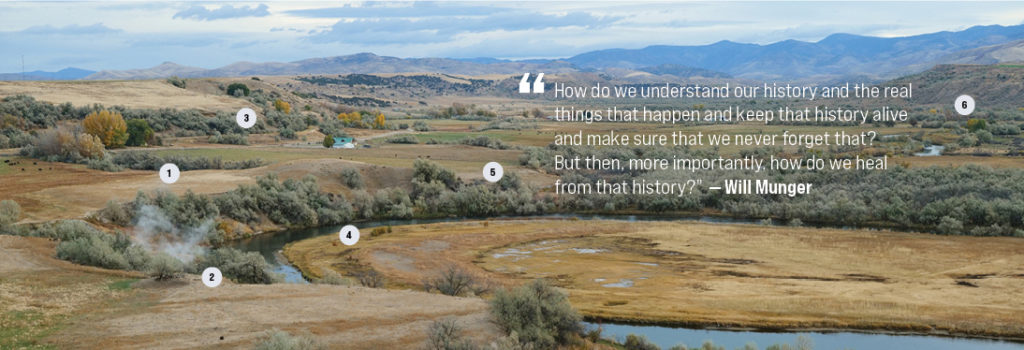

Drive north along Highway 91 just past Preston, Idaho, and you’ll round a curve that opens to a panoramic view of the Bear River bottomlands below. On a cold winter day, if you know where to look, you can still see steam rising along the river’s edge.

One hundred and fifty-eight years ago, it was at that spot that some 500 members of the Shoshone tribe were spending the winter, as they always did. Hot springs nearby provided a welcome place for them to catch their breath and catch up with friends and family during the cold winter months. They called it Home of the Lungs, or Mo-so-da Kahni.

A half-mile to the east, Col. Patrick E. Connor and his 220 cavalry soldiers had that same birds-eye view in the early morning hours of Jan. 29, 1863, as they made their way down a ravine toward the sleeping village and steaming waters.

When something terrible happens in a place where human lives are lost, it takes on new meaning—the 14.6 acres of the World Trade Center, the beaches of Normandy, a homemade memorial at the side of the road where a traffic fatality occurred. Places that haunt and hurt for the wounds they hold, but still compel us to keep going back for some unexplainable comfort.

Darren Parry feels a connection to this sacred ground where his people lived and died, as much as he does to the plants and the trees that once flourished here.

For Darren Parry, his solace is in knowing that around 400 of his people still lie there just beneath the surface. He is the former chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, after stepping down this past summer to run for Congress. In January of 2018, he finalized the purchase of 550 acres of this hallowed ground as a lasting way to honor and protect their memories, he says. It is the site of the largest massacre of Native Americans in the Western United States. The deep irony of having to purchase land that was once theirs is not lost on him, but neither is its significance. These are his ancestors whose lodges were burned to the ground and whose babies and children were slaughtered during a four-hour rampage in which few escaped. Those who did, never returned. A pall hung over the landscape. What was once a blessing had become a curse.

That is why today Parry especially marvels at what seems to be rising from the ashes. He says purchasing the land is helping his people renew their connection to it while providing new impetus as stewards. Voices that have been silent for more than a century and a half, are beginning to be heard again, he says. And new alliances are being forged between the Shoshone and businesses and community members, and Utah State University, to help bring back what his tribe thought was forever lost.

Will Munger, a USU Ph.D. student in the Department of Environment and Society, vividly remembers his first visit to the massacre site as a third grader. His USU Edith Bowen Laboratory School teacher, Steve Archibald, took the class on a fieldtrip there. “It made a deep impression on me,” Munger says. “The story of the hurt that was inflicted on the Shoshone, I could see that hurt inflicted on the land. This was in the early 90s when we went out there, and the site was trashed.” He began to make a connection between violence done to people and the degradation of land. It sparked his curiosity.

“How do we understand our history and the real things that happen and keep that history alive and make sure that we never forget that?” he asks. “But then, more importantly, how do we heal from that history?”

Parry has been grappling with those questions throughout his life. He talked about them at his newly built home in Providence in which he still managed to find some space in his suburban yard to include a full-size teepee.

When something terrible happens in a place where human lives are lost, it takes on new meaning—the 14.6 acres of the World Trade Center, the beaches of Normandy, a homemade memorial at the side of the road where a traffic fatality occurred. Places that haunt and hurt for the wounds they hold, but still compel us to keep going back for some unexplainable comfort.

“I look at the Earth and what she has provided as the same thing,” he says. “I don’t differentiate. I believe in Mother Earth and she is hurting in so many aspects by the way we live today, but especially out there because such an atrocity took place that we really haven’t acknowledged.”

Following the purchase of the 550 acres, he says most of the tribal members seemed content with keeping things as they were, but he saw something more. “We really need to tell the story of our people here,” he told the tribal council. “And we do that with an interpretive center and restoring the land to what it was.”

Soon after, he got in touch with faculty from the S.J. and Jessie E. Quinney College of Natural Resources that eventually opened the way for Sarah Klain, assistant professor in Environment and Society, and her graduate students from the Climate Adaptation Science Program—”a jolly band of misfits,” as Munger describes themselves—to help the tribe create a habitat restoration plan as part of their science studio project.

Munger also calls himself a co-facilitator, because “we’re co-producing science together” and this particular site has a lot of unique challenges.

With help from USU graduate students and faculty, invasive plant life such as cheatgrass, Canada thistle, and Russian olives will eventually be replaced by plants and trees known to have flourished at this Shoshone winter camp.

“We’re working in the Bear River watershed that spans Wyoming, Idaho, and Utah,” he says. “There’s a complex series of dams and irrigation systems. The water quality issues present at the site are the result of land management practices throughout the watershed. We have to think about the human relations and systems the site is embedded in.”

What that means is finding ways to bring the right people to the table to develop complex solutions to complex problems surrounding the environment—not only at the massacre site, but threatened landscapes throughout the Interior West. “These include farmers, scientists, native peoples, and students,” Munger says. “What’s amazing about this project, in particular, is the way it forces us to look at our history. The Shoshone have given a real gift to Cache Valley and to the world because they’re thinking about how they will steward this site of great pain and suffering to show the resilience and the capacity to adapt as a people.”

Parry is halfway through a $6 million fundraising campaign with plans to break ground for the new interpretive center within the next two years. In November of 2019, Brad Parry, Darren’s cousin, and a tribal councilman who worked for the Bureau of Reclamation in water quality and land development, was hired full-time as project manager.

- Location of the largest portion of the village where some 500 Shoshone were living on Jan. 29, 1853.

- Natural hot springs warmed and rejuvenated the Shoshone who wintered here every year. They called the area Mo-sa-da-Kahni, “Home of the Lungs.”

- Hillside from which a subset of Col. Patrick E. Connor’s 220 cavalry soldiers descended upon the village in early dawn.

- The Bear River, known to the Shoshone as Boa Ogoi, or Big River, is where villagers tried to flee from the attacking soldiers by jumping into the freezing water with their children.

- The land surrounding the massacre site still contains the remains of slain Shoshone.

- It was from this ridge that Connor’s cavalry descending through a ravine, about two miles east of the village, in the early morning hours of Jan. 29, 1863.

Their grandmother is Mae Timbimboo Parry. She heard accounts directly from tribal elders who survived the massacre, including her grandfather, Da-boo-zee, who later took the name Yeager. In the rich tradition of Native Americans verbally passing stories down from one generation to the next, she taught her grandsons what life was like along the Boa Ogoi, or Big River.

The Parry men learned where the village with its 70 teepee lodges was located. They learned how important the hot springs were for their daily use, and how visiting bands from all around would gather there for their annual Warm Dance celebration to hasten the coming of spring. They also learned where most of the killing took place, where the women tried to escape by jumping into the river with their babies, and where their great, great grandfather Yeager, who was only 12 at the time, laid in the snow for four hours with his grandmother, sparing them death by playing dead.

“My very earliest memories of grandma were here and her telling me about this,” Brad says. “She wanted me to know about what happened here and what an awful thing it was. She wanted me to know where my ancestors came from, and she wanted me to know that I belonged here.”

He is standing on the east end of their new property in a plowed field flanked by an agricultural canal that flows among stands of Russian olive trees. Nearby, the jolly misfits were together discussing the various components of the work they accomplished over the summer and what still needs to be done. That is because, in truth, it’s a decades-long program that can keep students busy for years to come.

“We want this to be long term,” Brad says. “We want Utah State and Professor Klain to keep bringing students up here to help monitor and protect everything that we are going to do.”

It is a tall order, and a complex one, as Munger points out, but his team of graduate students have already indexed and cross-referenced the site’s plants and trees with detailed ethnobotanical records kept by Mae Timbimboo Parry. In addition to chronicling the plant life, Sofia Koutzoukis, a Ph.D. student in wildland resources, researched how a changing climate might impact these plants in the future by using species distribution models. It could prove to be instructive to talk about how some plants that thrived in the late 19th century may not be able to survive, without some extra care, in the coming decades, Munger says.

Restoration of the site also involves cleaning up Beaver Creek that runs through the property and into the Bear River.

Over the years, Mae methodically recorded all of the plants that were used for food, medicine, and ceremonies by her people. That means the plants and trees that the students now know were once there, such as willows, cottonwoods, mint, sage, sego lilies, and camas, will be brought back as the invasive habitat is removed, such as cheatgrass and Russian olives. Munger says cultivating indigenous species like willow and cottonwood can support the abundance of birds and insects. But to bring back willows and cottonwoods you have to think about how water moves through the site.

That is why restoration also includes plans to clean up Beaver Creek that runs through the property and then flows into the Bear River. It is currently loaded with suspended sediments and phosphorus from overuse of fertilizers. The degraded condition of this creek means that aquatic life once there can no longer survive. The geomorphology of the stream has changed as well. It has been incised and cut down and shunted along the road to the point where it is now just an irrigation runoff ditch, Munger says.

“My very earliest memories of grandma were here and her telling me about this. She wanted me to know about what happened here and what an awful thing it was. She wanted me to know where my ancestors came from, and she wanted me to know that I belonged here.”

Brad Parry

To change this, they turned to Lindsay Capito, a master’s student in watershed sciences who tapped into research on how you can restore watersheds naturally by changing the flow of water by introducing beavers that build dams. Capito, along with assistance from USU watershed science alum Kyle Todecheene, a Navajo from Monument Valley, are also mapping the river using geographic information system (GIS) models to determine where beaver dams may be appropriate with tools developed by researchers from USU’s ET AL lab. “And the cool thing about this project is we’re not starting from nothing,” Munger says. “Local ranchers and groups like BioWest, Utah Conservation Corps, and the Bear River Land Conservancy have tried to do this sort of restoration project. And so there is knowledge already in the community that we can begin to draw on.”

Healing begins when you bring people together, Munger says. In the future, this might involve organizing riparian buffers and conservation easements with farmers and ranchers upstream to help improve the water quality and changes to road cuts or infrastructure engineering that might help improve water quality. And most certainly, it will involve people on the ground to make it happen. That could come quite naturally through the collaborations between Shoshone youth and students from Preston, Logan, and around the region. “This would be such a great spot for young people to participate in a living-learning laboratory,” Munger says.

The partnership between the Shoshone and USU will extend for years and span disciplines from ecology to instructional technology.

Social impacts are also being considered at the site. Klain, co-instructor of the Climate Adaptation Science studio project that brought all of these students together, added a social science component by bringing in graduate research assistant Cole Stocker. His task is to interview locals who own or work on land and have ties to the massacre site. He is interviewing landowners to learn from their experience working on the land, their perspective on what will take place at the site, as well as their opinions about future plans. They are looking for potential red flags. For example, introducing beaver for habitat enhancement and river restoration could prove controversial. “So we want to know if that will be a problem for people who live near here or not,” Klain says. This is the kind of feedback that could prove highly useful to Shoshone members as they plot the site’s future, Brad says, especially if it helps to prevent a repeat of the mistrust and misunderstanding that contributed to the tragic events of Jan. 29, 1863.

While Munger and his colleagues are focused on the habitat in this restoration effort, Breanne Litts is laser focused on the people. She is an assistant professor in the Department of Instructional Technology and Learning Sciences and a recipient of a five-year $1.15 million National Science Foundation grant to help tribal youth create place-based storytelling experiences. These will be stories that users can pull up on their mobile devices in specific locations around the site.

“Just like the habitat restoration is important and significant, the preservation of the actual people and the knowledge in the tribe and the culture is incredibly important,” Litts says. “They have only 500 or so members in their tribe. They have a single digit number of people who know the language, and a single digit number of people who have the story of the Bear River Massacre site in their head.”

It is through traditional oral means almost exclusively, she says, “and so like Darren always says, ‘when an elder dies, a library dies with them.’”

Part of the USU team’s work will involve restoring the land to its native habitat, including cottonwoods, willows, mint, sage, and camas.

The emerging reality of being able to, at long last, tell their story in the actual place and setting “as though it was the day before the 29th” has changed what was once “a feeling of sadness and of darkness” when at the site, to that of peace, Brad says. “For the first time in 40 years, I feel like this is home now.”

It is a coming home story that up until now, was relegated to roadside explanations removed from the site itself. Plaques created by the Daughters of Utah Pioneers placed on a pyramid-shaped stone monument with a miniature teepee atop its truncated cone. A 1932 plaque calls the genocide a “battle” and refers to “combatant women and children,” while a 1953 marker gushes over the pioneer women “trained through trials and necessity” who tended to the wounded soldiers.

The Daughters of Utah Pioneers plan to replace the 1932 plaque in time for this month’s annual memorial service at the site on the 29th. But Parry doesn’t want to see any of the original plaques completely go. He often talks about how history is written by the victors, but recognizes that even if they got it wrong, their accounts should be preserved in some way, if only to demonstrate, through these snapshots in time, evolving attitudes towards his people and their history.

“We’re just taking back the narrative,” he says. “It’s our story, let us tell our story. Whether you agree with it at the end of the day, that doesn’t matter, but we need to be heard.”

“Oh Great Spirit,” a Shoshone prayer begins, “whose voice I hear in the winds and whose breath gives to all the world, hear me.”

By John DeVilbiss

Read about Breanne Litts’s NSF grant to help Shoshone youth create storytelling experiences at the 550-acre site.

Watch Darren Parry explain the project.

Gregory Meacham January 18, 2021

Has any publication been made of Mae Timbimboo Parry’s botany records? If so, how might it be available?.

Brenda January 10, 2021

Wow!! I totally did unknow the history about this massacre. The powerful of the healing mission from those students is touching my heart.

USU Editor January 11, 2021

Brenda, this was definitely a story that warmed our hearts, too. Thank you for sharing.

Stan Balducci January 9, 2021

Can I make a donation to help with the plants habitat? thanks Stan BA in history, 2012..

USU Editor January 11, 2021

Hi Stan,

This is a question that has sent me on the hunt for answers. I will share what I find out. Thank you for supporting this effort.

USU Editor January 11, 2021

Hi Stan,

Brad Parry, project manager for the project, says that yes, people can donate to the restoration. He provided this info:

Northwest Band of the Shoshone Nation

707North Main

Brigham City, UT

84302