Dissected: Mapping Superhighways

Stefani Crabtree obviously wasn’t there, 50 millennia ago, when the first early humans set out to cross the supercontinent of Sahul.

She didn’t directly track the progress of people up steep canyon trails, across stretches of barren desert, or alongside the greenspace near cool springs. But she still knows a fair bit about how they traveled.

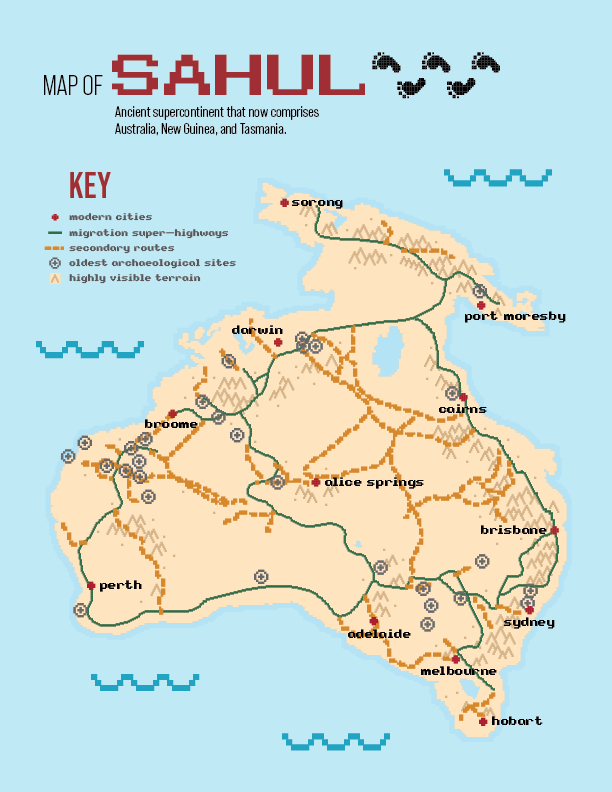

Crabtree and her colleagues model how ancient humans move. With a novel strategy that virtually simulates the decision-making of early wayfinders, the team mapped probable pedestrian “superhighways” across Sahul, the supercontinent that existed before splitting into Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania.

Early humans used methods that might feel familiar to many modern hikers, according to Crabtree, assistant professor of social-environmental modeling in Utah State University’s Department of Environment and Society. They sought out springs, used visual landmarks, looked for safe and comfortable places to shelter, and didn’t climb a steep hill if they didn’t have to.

To decipher the ancient pathways, the team first virtually drained the oceans that now separate mainland Australia from New Guinea and Tasmania. Using hydrological and paleo-geographical data, they reconstructed inland lakes, major rivers, promontory rocks, and mountain ranges that would have attracted the gaze of a wandering human. They created avatar programming for early human travelers and gave them the realistic goal of staying alive. These modeled humans were drawn to water and other landmarks, while the calorie outputs of their efforts were measured.

“In a new place, they would have to make decisions about efficiently moving throughout the space,” says Crabtree, “where to find water, and where to camp — and they would orient themselves based on easily visible high points.”

The algorithms simulated a staggering 125 billion possible pathways, and patterns emerged: the most-frequently traveled routes carved distinct “superhighways” across the continent, forming a notable ring-shaped road around the right portion of Australia; a western road; and roads that transect the continent. A subset of these superhighways map to archaeological sites where early rock art, charcoal, shell, and quartz tools have been found.

The project is the largest reconstruction of a network of human migration paths into a new landscape and the first to apply rigorous computational analysis at a continental scale. It won the Hyperion High Performance Computing Innovation Award — the first time an archeological-centered study has earned the prestigious honor.

The research could shed light on other major migrations in human history, such as the first waves of migration out of Africa at least 120,000 years ago. It also helps to narrow the search for undiscovered archaeological sites, forecast movements of current human migration (as a result of climate disruptions, for instance), and help researchers better understand how aboriginal groups connect to other human populations.