Wonders of Collaboration

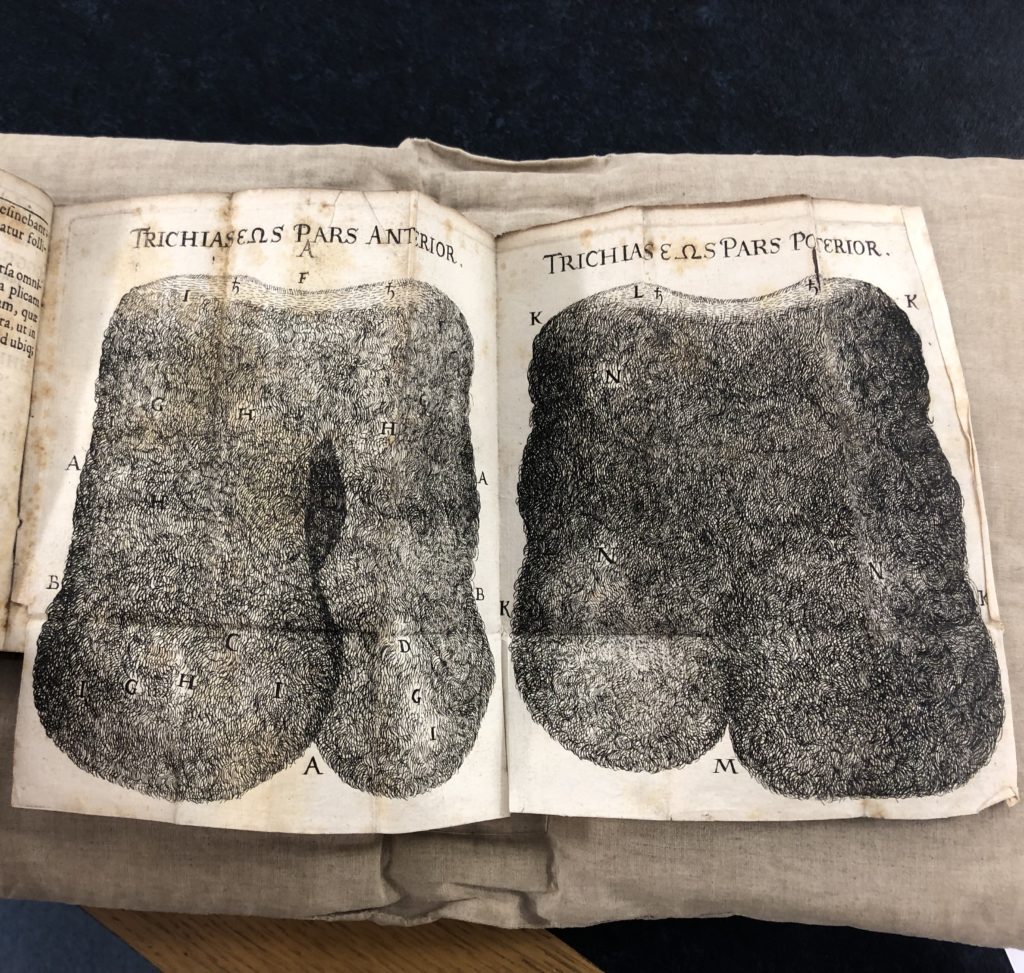

“Wondrous Hairy Disease” took the life of a 17th century woman in what must have been an agonizing death.

A 400-year-old autopsy report describes that she suffered from a hairy tumor that took eight years from its onset before it killed her. The tumor caused her abdomen to extend by about a foot, and made breathing difficult because of the way it pressed on her diaphragm. Whether the tumor was malignant or benign was inconsequential because cutting it out was not an option. Anesthetics had not been developed.

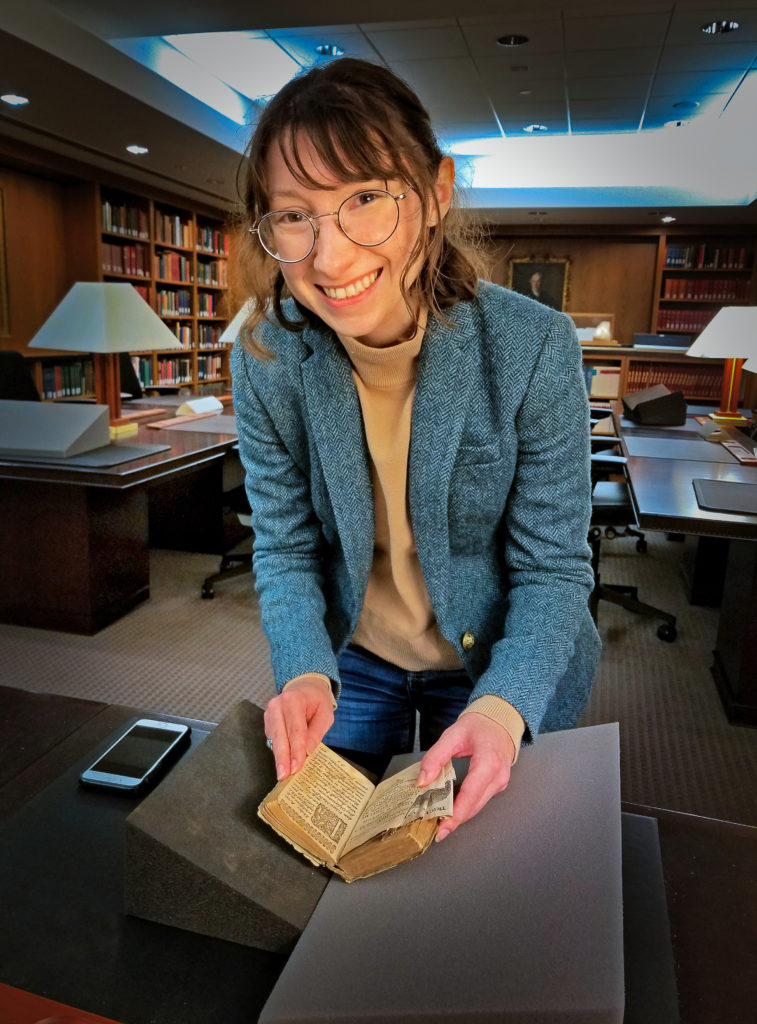

She was a woman who leaped off the page for Mark Damen, Utah State University professor of history and classics, when his former Latin student, William Lensch, ’91, asked for his help in translating the medieval medical text detailing her cancer. Lensch, now strategic advisor to the dean in the Harvard Medical School, believed he had come across the first documented case of a reproductive system teratoma in Harvard’s medical archive. His Latin, however, was rusty. Damen enlisted help from another former student, Chuck Oughton, ’08, to translate the 15,000-word report which Lensch used for his research on teratomas and cited the text in a published report.

Meanwhile, the rare translation sat on Damen’s desk for another 10 years whose whisperings he could not entirely shut out. He knew the text lacked historical perspective. He also knew that a recently recruited grad student in history, Kristen Brady, was interested in historical medicine. Would she be willing to take it on as an interdisciplinary project?

Kristen Brady holds a medieval medical text as illuminating today as it was 400 years ago. Photo courtesy of William Lensch.

“Oh yeah!,” she told him. “This is actually the kind of work I really want to be doing.”

That is because shortly after Brady arrived in 2018 to study social history, she experienced some personal health issues that caused her to pore through medical journals, teaching herself how to read them. “I actually really started to enjoy it,” she says. Brady came across a few history of medicine articles that weren’t “very good history, to be honest,” she says, “but those articles still meant something to me as a patient.”

“Most people don’t know that or talk about it, despite the clear correlation … Why did that lead to so much care for breast cancer but not ovarian cancer? The fact that we are still seeing that dichotomy over 400 years is kind of alarming.” – Kristen Brady

She realized that historians of medicine have access to a large demographic because everyone is, in a sense, a patient. “There’s this entire audience that is kind of being untapped because we, as historians, are really focused on creating an historical narrative specifically for other historians,” she says. “As soon as I started uncovering this narrative, I was kind of like, okay, this is how I make history useful.”

For her, the autopsy report of this 17th century woman demonstrated how an important story emerged from a single find because one person cared enough to share and consult with others about it. That case has taken on more relevant meaning, not only because it better informs scholars today about diseases and medical procedures in early modern times, but also establishes a meaningful diagnostic benchmark for today’s researchers.

Brady found, for example, a dichotomy she hopes to use to emphasize cancer research for ovarian cancers and reproductive system cancers. After scouring the libraries of Harvard and Cambridge, this germ cell teratoma from the 17th century was the only case she found. And yet simultaneously she found a myriad of cases documenting breast cancer in historical texts, but not on related reproductive system cancers. “And what really struck me is how that actually connects to the kind of epidemiological trends that we see in medicine today,” she says.

With earlier screening and detection for breast cancer and discovery of the BRCA gene mutation, mortality rates have dropped some 39 percent over the past 20 years. Yet even so, far too many people don’t realize that the breast cancer gene mutation also points to an increased risk for ovarian cancers, she says.

With earlier screening and detection for breast cancer and discovery of the BRCA gene mutation, mortality rates have dropped some 39 percent over the past 20 years.

“Most people don’t know that or talk about it, despite the clear correlation,” she says. “And so my question is, why did that lead to so much care for breast cancer but not ovarian cancer? The fact that we are still seeing that dichotomy over 400 years is kind of alarming.”

Questions like these are important to Brady, but you cannot ask the right questions if you do not have the expertise of medical historians, classicists, researchers, and physicians working together to identify diseases from the past to see how they compare today. “Are we making progress toward diagnosing and treating them?” she asks. “If not, what does that tell us?”

Surprisingly, the notion of working in such an interdisciplinary fashion is still fairly novel among historians because of the methodology it involves. The idea of retro-diagnosis without biological evidence is concerning to some historians. Brady believes, however, that it creates a chronology of medicine. “It re-associates medicine with its pre-germ theory days and that’s really important because that affects how we interact with patients and study things,” she says. “‘Wondrous Hairy Disease’ is what they called this in the 17th century, but that does not mean it’s not associated with the germ cell tumors we know today.”

Illustrations of a hairy tumor, a germ cell tumor that took the life of a 17th century woman, the first documented case of a reproductive system teratoma. The one of-a kind text was translated at USU. Photo courtesy of William Lensch and the Center for the History of Medicine at the Countway Medical Library, Harvard Medical School.

The early-modern autopsy was so detailed that it is nearly impossible to conclude it is not an ovarian germ cell tumor. Because these tumors are stem cell based, they can grow any tissue on the human body—hair, teeth, bones, sometimes an entire finger or ear, Brady says.

“It’s very strange. And so when you see one, it’s kind of like we don’t really need serological proof because it’s so physical … Because it is such a clear-cut case for us, we can actually use it as a starting point for this conversation.”

The ability to contextualize such conversations motivates Brady to want to eventually teach the history of medicine at medical schools. “When we start to get history scholars collaborating with

practitioners and scientists, then we are helping them to think critically and analytically and historically in ways that helps them to interact with patients,” she says.

History that spawns new ideas and can shape the course of medical history. The kind of history Brady likes. The kind that is useful—not only for identifying diseases from 400 years ago, but to find cures for them. And how wondrous would that be?