What do the memes we share say about us?

In mid-January, the internet was awash in sea shanty videos on TikTok.

A week later, memes of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, bundled in a Burton coat and sweater mittens, made the rounds on Twitter. Within minutes, Sanders, originally photographed at the January 20 inauguration ceremony, was Photoshopped sitting on a subway, perched on the iconic Friends couch, and on the White House lawn near a boy pushing a lawnmower. Where do memes come from and why do we love them so? Lynne McNeill, MA ’02, associate professor of folklore at Utah State University and co-founder of the USU Digital Folklore Project, says memes are another way we communicate ideas—big and small.

The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Kristen Munson: Let’s start with a brief history of memes. When did folklorists decide to start collecting and interpreting them?

Lynne McNeill: Folklorists began collecting memes even before “internet meme” was in the vernacular of most people. The publication that kicked off studying folklore on the internet was Trevor Blanks’ book Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World by Utah State University Press in 2009, but folklorists had already been studying jokes and urban legends on discussion boards, bulletin boards, and email listservs in the late 80s, early 1990s. Of course, no one really could predict how common use of the internet would be for everyone. Early on, people used the term “image macros” to talk about a picture that would get repeated with different bold font over it—what we think of as the most basic internet meme. Internet users adopted the term “meme” from the work of Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist who defined memes as the cultural analog to genes that move around in the gene pool. He suggested that memes do the same thing in our brains. They jump from brain to brain; they are like ideas, concepts, trends, sticky thoughts, and they evolve to fit their environment. And this is basically what folklorists would say about folklore. For instance, if we tell a good story about Boston on the East Coast we can tell it about Salt Lake City and make it relevant. Folklorists recognized memes as this dynamic but traditional patterned, expressive culture that we use to symbolically communicate with one another and sometimes say serious things to one another in silly ways.

Where do memes originate?

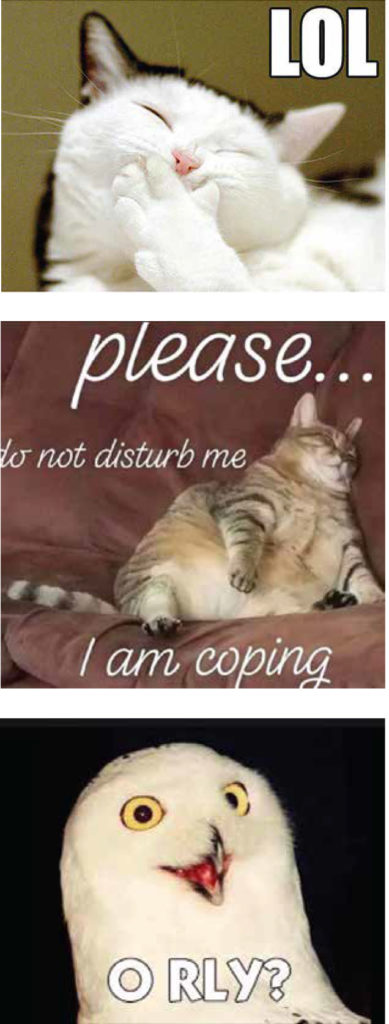

LM: There are meme generators where you can take a preexisting picture or upload your own and make one into that visual meme format. Memes began in the murky depths of the internet. One of the earliest image macros was that surprised looking owl that just says “O RLY?” Shortly after that we got LOLcats and I Can Has Cheezburger? But folklorists aren’t focused on origins these days. In the past, folklorists were interested in uncovering the origins of folksongs or fairytales and tracing them through time and space, until one day, the discipline realized, its origins aren’t why we sing songs or tell fairytales now. That is not really where the significance is. It may relate to the origins, but for us, the significance is what the story or song or internet meme articulates symbolically for us right now.

Why do people use memes? What purpose do they serve?

LM: When we sing a song or tell a story or share a meme, we are doing some form of symbolic communication and tapping into the authority of tradition. We may put a twist on it, but we base it on a preexisting example that came before, a process we call tradition. We often consider tradition something that mires us in the past and holds us back, but really, tradition is a process of innovation. Tradition is taking precedent, reshaping it, and putting it back out there for a new use, in a new context, for a new audience. In a lot of ways, internet folklore isn’t that new. It is the exact same thing we have been doing with songs, stories, customs, and rituals all along throughout human history—we just have this new medium to create expressive culture that isn’t just verbal or material or behavioral, but a combination of all of them. Folklorists divide the genres of folklore into four main categories: things we say, things we make, things we do, and things we believe. Which are internet memes? Memes are verbal but they are also a form of art and an action. Even just appending a hashtag to a tweet is like giving someone a secret handshake. Memes are a new multivalent way of expressing ourselves in a form that we are really used to doing.

I’m curious what memes today are saying about our society. How do you characterize the memes that you are seeing and tracking? Are we angry? Are we happy? Are we depressed? Are we anxious?

LM: The answer to all those questions is yes, we are all those things, and yes, we make memes to show that we are all those things. The USU Digital Folklore Project began in 2014 and it’s really poignant to go back and look at the different number one trends our voting panel chose as the trend of the year. We say “trend” because we also look at viral customary behaviors like planking that aren’t always an image macro with the image and the text. The winner of 2020’s digital trend of the year how it started/how it’s going is a great example of what memes can say about our society. 2020 saw a prevalence of genres that feature conversations of the past with the present or two people with each other such as the whole platform of TikTok offering the duet feature where someone makes a post and another person can actively be in conversation with them in their own post. What that tells us about us is that we have had a year that, if it did nothing else, it broke our expectations. We needed a traditional, regulated format in which to say what the heck just happened? Here is how I thought stuff was going to go, and this is what I ended up with: this insane pandemic, politically strife filled world.

How it started / how it going felt spot on for 2020.

LM: If you look at how that meme began, it was very benign and often used in relationships. The first use of it that we know of was of a person posting a picture of their first chat conversation with another person and then their romantic relationship status. That format where the past can be in conversation with the present and the expectations are either met or broken, just became what we all needed to talk about 2020. And that could be funny, it could be awful, it could be heartbreaking, it could be poignant, it could be bittersweet, but what it speaks to is a break in expectations in all possible ways.

Are your noticing changes in the memes we use over time or in how they evolve?

LM: We have two categories in the USU Digital Folklore Project: social issues and serious fun. We came up with those two categories because trying to rank trends against each other with regards to cultural significance is hard because it’s not just apples to oranges. Sometimes it’s a matter of apples to Nobel Peace Prizes, as my co-founder and co-director of DLP Jeannie Thomas has said. How do we hold up cute cats to the #MeToo movement? Often we use fun things to make serious commentary so that’s why it’s called serious fun. The past two times that serious fun has won the overall category are the past two presidential election years. There were a lot of election memes and things like that on the ballot back in 2016, and yet, the fervent and often terrifying belief that bizarre and scary clowns were stalking us in our safe spaces somehow resonated more. And when you look at that as a comment on the election year it actually makes sense—we needed a metaphor for what this feels like. And I think that’s see we are seeing now in 2020. The ballot was full of politics and COVID-19, but this meme that is less a topic and more a perspective is what won. This meme that says whatever you thought was going to happen is not what you got.

A mere two weeks into 2021, have any memes emerged that reflect where we are headed?

LM:The how it started/how it’s going meme is still going strong because we still need it. I think one of the things we are seeing is so much fear and chaos that people are a little bit frozen. We see what we always share in times of ambiguity and tension—urban legends and rumors. Those are two of our biggest forms of folklore in any situation of high anxiety and personal safety. Urban legends, rumors, conspiracy theories are forms of folklore that were some of the first to show up online. We are seeing tons of that now and those are the coping genres that we turn to when we have a void of information and want to think we can begin to know what’s happening. Jokes are how we cope and process when we know what’s going on and we hate it; legends come in when we hate it and we don’t even get it. We see these different genres filling these different needs. Escapism and wish fulfillment are always huge. I think that’s why we are seeing sea shanty TikTok take off.

Break that one down for me.

LM: Sea shanties are traditional folksongs from seafarers. The Wellerman is a wonderful traditional folksong. TikTok users are singing duets that become trios that become quartets that become quintets and they are all taking on different parts. It’s this beautifully collaborative, supportive moment and now there are reaction videos on top of that. You can see the collaborative nature of folklore just being this thing we need on the internet right now as a counterpart to all the divisiveness. It’s the old school action of singing together, communally producing art together, but doing it in a socially distanced way.

There is something kind of beautiful about people stuck at home alone being able to sing the same thing together right now.

LM: I think we all have a greater appreciation of collaborative projects and the ways that technology is enabling us. TikTok is a platform that is largely disparaged, and yet suddenly we are seeing this opportunity for conversation and response. The function on TikTok is called duet, but sea shanty TikTok is turning it into literal duets where people across the world are able to sing together. The value isn’t just for the people who can sing it together, the value is for all of us as well, vicariously experiencing that sense of collaboration and connection.

Why is Congress not doing TikTok videos? Maybe that is the path forward.

LM: A few years ago, folklorists did a special journal issue on fake news, which, in many ways is indistinguishable from legend and rumor, it just originates in a more malicious place. But once it takes off, it moves and functions just like legend and rumor. One of things that people often say is that we all need to become better readers and critical thinkers and fact checkers. But my contribution to that journal issue pointed out that that solution assumes social media is reading, or print media, and it’s not. It’s talk. And that’s the problem. Conversation has different norms than print media does. Where maybe we think to fact check print media, it’s not natural to fact check conversations. When we see social media as talk instead of writing, we realize the ways to counteract it are going to have to be ways that come from speech more than from research and writing. I am not saying folklore is going to save the world, but once we identify the nature of the communication causing a lot of our issues, such as a lot of these conspiracy theories and rumors moving through these folk vernacular spaces, the solution is going to have to be something that moves through these folk and vernacular spaces as well. I love the idea that Congress would be making TikTok duets and maybe we would be doing better.

What can the everyday person learn from memes?

LM: Memes like all folklore are really like a barometer of group sentiment. We can understand that when rumors and legends and conspiracy theories are flying, it’s like taking the temperature of a room: we are anxious, we are stressed; we do not have the information we need. Oftentimes when jokes, especially dark humor, are circulating, there is a big issue that we understand but feel conflicted about. One of my favorite things from the ballot this year was the level up challenge where you stack your toilet paper in increasingly high levels and have your pets jump over them. The tradition became this wonderful communal thing. Many people were stuck at home with their pets and hoarding toilet paper, and doing this fun silly thing made us feel less alone. The nice thing is we can feel it and live it and experience it as a member of the folk by filming our own dogs and cats, or we can see the pattern of this traditional behavior playing out online that tells me that people are bored and creative and they want to connect. It’s a visual dramatization of quarantine life and making connections with one another, and that is no small thing.

Any last thoughts on memes?

LM: Folklore studies has a concept of an active bearer versus a passive bearer of folklore. Active bearers are out there telling stories, they’re the ones that push everyone to get together for Thanksgiving dinner at Aunt Shirley’s. A passive bearer is someone who could absolutely sing you a song if you asked and who knows how to have Thanksgiving dinner at Aunt Shirley’s, but who doesn’t lead the charge on those traditional activities. And we see that with digital folklore, as well. Don’t feel bad if you have never made a meme—it doesn’t mean you aren’t a part of digital culture or that you aren’t still a passive bearer, which is a really important skillset on the internet, to be able to parse these messages. When we talk about culture online, often we talk about dog whistles, and are you really prepared enough to even hear what is being said? You can look at digital culture and say ‘I am never going to make a meme.’ Or you can look at it and say I am a listener of digital culture, I am a watcher, I am an observer, I am a thinker, and I am going to pay attention to the big things that are being said in this seemingly trivial format. A lot of people who say ‘this isn’t my milieu, this isn’t for me,’ well, it’s a little more their milieu than they think.

By Kristen Munson

Photo collage by Liz Lord ’04 and Pixabay.