Kolaches, Kin, Cather, and Culture

“A loving word is even better than a sweet kolache.” – Czech Proverb

The iconic Czech pastry known as kolaches is a delicacy made with a supple, raised sweet dough and filled with any number of traditional fillings, including cottage cheese (the Czech version of cheesecake), poppy seed, or spiced plum.

Kolaches are to Czech culture as apple pie is to American. They are as much an expression of the cultural values of tradition, hospitality, resourcefulness, and artistry as they are a dessert staple, and nearly every special occasion from a wedding to a Sunday afternoon visit with friends is marked by a heaping plate of them on the table. Any Czech cook worth their salt is both expert at the intricacies of the recipe and unyielding in their stance on about the “correct” way to bake kolaches.

Does your recipe include the sweet crumble topping called posipka? Yes, please. Can you use pie fillings as modern substitutes? I’d really rather not. Are they round, square, or folded? Um, round, of course! Can kolaches come in versions with savory fillings? Heavens, no! A jalapeño-cheese kolach is a Tex-Czechs abomination! (Sorry, my Texas friends).

Now that you know where I stand on these important controversies, let me admit that such debates highlight issues of authenticity versus regional adaptations. In other words, the history of migration is written on the humble kolach.

Kolaches also symbolically mark one of the places where my own personal history meets my professional research and scholarship. As an American Literature professor, I have spent the last three decades researching the novelist Willa Cather, with much of that time focusing on her portrayal of Czech-American immigrants, such as her famous depiction of Ántonia Shimerda Cusak in the 1918 pioneer novel set in Nebraska entitled My Ántonia. I come by my interest in Cather’s Czechs serendipitously, for my own Czech mother’s name was Ántonia.

Evelyn Funda’s mom Toni escaped political strife in the old country and eventually moved to Idaho where she married another Czech-American.

Like Cather’s character, she escaped political strife in the old country (in her case, the Soviet Communist takeover after World War II) and arrived here almost penniless. She moved out West to Idaho where she married another Czech-American and made a comfortable, if not prosperous, life on a farm. Also like Cather’s character, outside our back door she kept a cellar filled with jars of fruits and preserves, and she was known for her light-as-air kolaches—among the many traditional Czech foods that she regularly put on our table.

I’ve written about my own Ántonia in a memoir entitled Weeds: A Farm Daughter’s Lament, where I describe my paternal grandfather’s immigration to the United States in the first decade of the twentieth century, at the height of Czech immigration. After working as a baker for two years in St. Paul, Minnesota, Frank answered the lure of western settlement and came to southern Idaho, where he both homesteaded and worked as a baker until he could devote his time entirely to his farm. Like Cather’s main character in Neighbour Rosicky, my grandfather Frank believed that owning his own land offered a liberty that made life “complete and beautiful.”

Thus, my Czech family as a whole inspired my current research project, a book entitled Willa Cather and the Czechs, which considers how Cather, who descended from Welsh and Irish ancestry and was born on a fourth-generation sheep farm in Virginia, could so accurately depict the unique challenges of Czech immigration to the American prairies in a number of novels and short stories. As I have studied Cather’s interests in Czech politics, music, literature, mythology, and, of course, foodways, I have recognized her compassionate and nuanced portrayals of European immigrants from Germany, Scandanavia, and Eastern Europe.

Within the anti-immigrant climate of the early twentieth century, those immigrants were more often stereotyped and viewed with suspicion. But Cather honored the intelligence and imagination these immigrants brought to America, arguing that they had contributed significantly to the prosperity of the nation.

Regarding Czech immigrants specifically, Cather called them “people of a very superior type” and cited their “sturdy traits of character,” “elasticity of mind,” and “honest attitude toward the realities of life.” As for the superiority of their pastries, Cather believed they were an indication of true cultural sophistication. “I could name a dozen Bohemian towns in Nebraska,” she wrote in 1923, “where one used to be able to go into a bakery and buy better pastry than is to be had anywhere except in the best pastry shops of Prague or Vienna.”

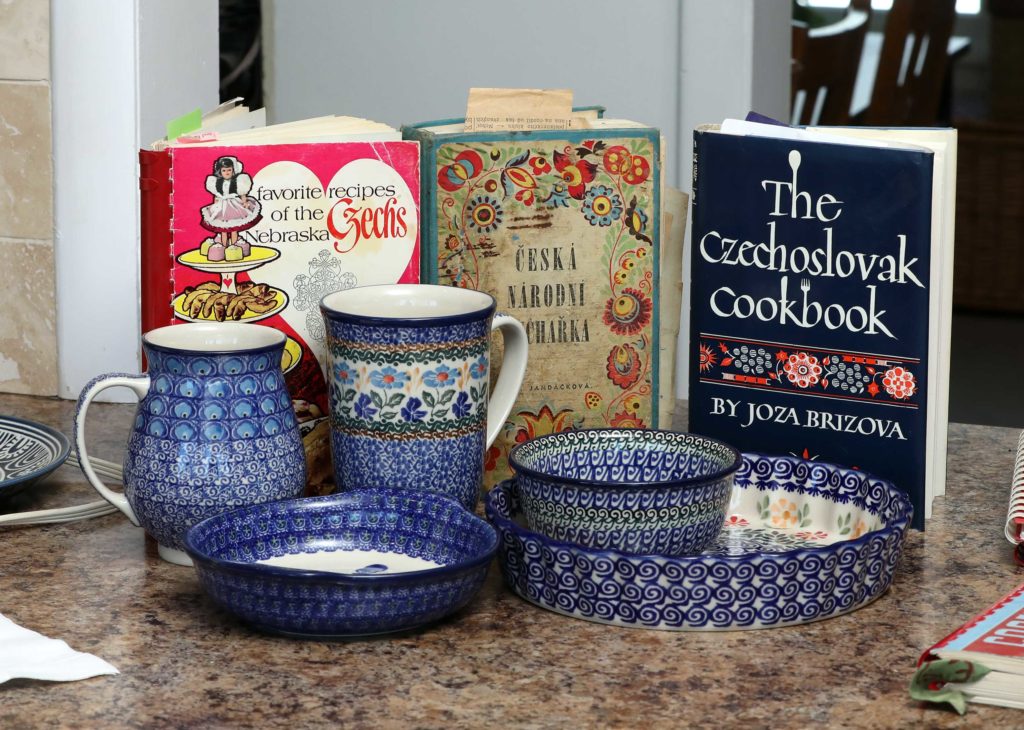

Some of Evelyn’s Czech cookbooks, including her paternal grandmother’s 1954 cookbook written in Czech.

Cather’s Ántonia had been patterned after a childhood friend from Nebraska, Anna Sadilek Pavelka, who Cather once called “one of the truest artists I ever knew.” In a 1921 interview reprinted in Willa Cather in Person, she cites “the order and harmony of her kitchen” and the “real creative joy of all her activities.” With Anna, Cather said, “Art springs out of the very stuff that life is made of.”

We see this theme in Cather’s iconic fruit cellar scene at the end of My Ántonia where the novel’s narrator Jim Burden returns to Nebraska to visit his childhood friend and her large, exuberant family. He recognizes how the hardships of her early days on the prairies are far behind her.

Antonia’s children proudly show Jim their mother’s new cellar and draw his attention to barrels full of pickles and other preserves. “They said nothing,” Cather writes, “but, glancing at me, traced on the glass with their finger-tips the outline of the cherries and strawberries and crabapples within, trying by a blissful expression of countenance to give me some idea of their deliciousness.”

Then one of Antonia’s sons suggests she show Jim the spiced plums, adding “Americans don’t have those… Mother uses them to make kolaches.” In a comic end to the scene, Antonia’s youngest, impish son Leo “tossed off some scornful remark in Bohemian” to his brother, to which Jim quickly responds, “You think I don’t know what kolaches are, eh? You’re mistaken, young man. I’ve eaten your mother’s kolaches long before that Easter Day when you were born.”

Evelyn Funda, professor of English, studies western American literature and culture. She holds a batch of her mother’s famous kolaches.

In carrying on the tradition of baking kolaches, Ántonia suggests how successful assimilation does not mean giving up pride in her family’s national identity or faith in their cultural history. Yet, in Jim Burden’s teasing response to little Leo, the kolaches also symbolize cross-cultural connections forged over food, meaningful shared experiences that stand in contrast to the complexities of translating linguistic meaning between languages.

To my mind, that is the recipe for a powerful message.

By Evelyn Funda