Becoming a Master Gardener

The Graft

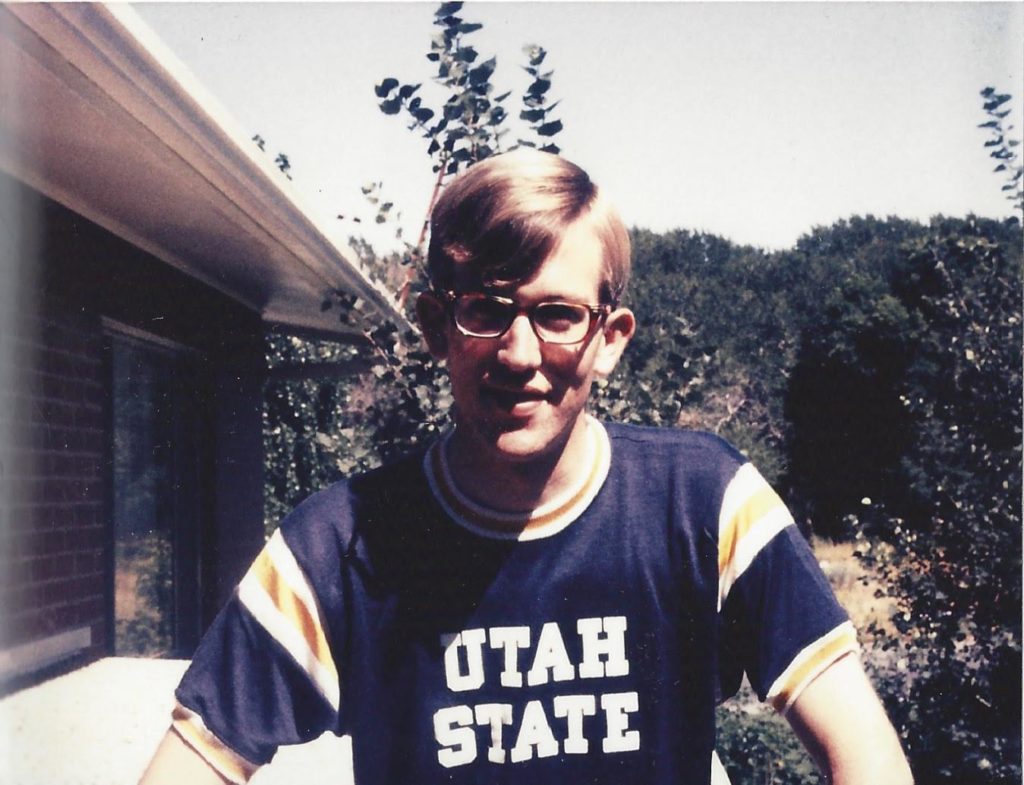

When people are grafted into a new family, they often compare upbringings and personalities to see how they measure up. I revere my father-in-law, J. Craig Hale ’70 (1946 – 2016). The former C.I.A. officer bests me in every dimension: Clearfield High School Student Body President, USU Man of the Year, USU Student Association Vice President, and graduate degrees from Stanford and Tufts universities. Among his accolades, he was a self-taught master gardener. He had few weaknesses, so when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease at age 55, it was a difficult blow. He retired from the agency shortly thereafter, moved back to Logan where he was raised, and built a garden to rival the Butchart Canadian Gardens, complete with raised beds and wheelchair-compliant walking paths.

A Budding Gardener

Dad believed that a garden’s utility was just as important as its aesthetic. He used to comment, “if you’re going to plant a tree, why not make it a fruit tree?” Dad loved freshly picked ears of corn; pesto made from garden-fresh basil; deep colored, almost black concord grape juice, and home-pressed apple cider. His rows of vegetables, patches of berries, and groupings of over 20 varieties of fruit trees provided all these and more.

During his time at USU, J. Craig Hale ’70 was the university’s Man of the Year and student association vice president.

Several years after building his Garden of Eden, his health began to decline quickly prompting our family to move closer to aid in his and his garden’s care. Dad would sit in a chair and point while I interpreted which weed he wanted pulled or branch he wanted cut. My efforts did little―dad seemed to will his garden to grow. It would produce more than enough food to feed his home and those of his nine children, with plenty remaining for neighbors and friends. Incidentally, he would often say he felt the garden was so productive because he gave much of the food away.

About a year before he died, dad pulled me into his office. He wanted to give me a gift. It was clear that, unqualified as I may be, my wife Amy and I were likely the future stewards of the family garden. He handed me several thick three-ring binders filled with agricultural fact sheets from USU Extension, news articles, and detailed ledgers of everything he planted by year and location. Dad was attempting to pass on his secret—knowledge.

That first harvest after dad’s death was lackluster. I was unable to operate the irrigation pump, the berries were noticeably chlorotic (lacking in iron), and I harvested as many water sprouts as tree fruit. If it hadn’t been for the efforts of Amy and Martha, my mother-in-law, the whole garden would have been fallow. It was during the planning for the upcoming season that I consulted dad’s binders: soil PH, micronutrients, fertilizer composition, blossom end-rot, thinning cuts, heading cuts—they read like a foreign language. It was clear that his gift would be of little use unless I had an interpreter. So, in January of 2018, I enrolled in USU’s Master Gardener (MG) program and began an eight-month journey to green-up my thumb.

T. Craig Hale watches over his garden.

Preparing

My first day of MG was like any other first day. I was nervous and my mind filled with irrational thoughts. Would my classmates judge me because I didn’t grow 100 percent organic? Was I hippy enough to fit in? What if they asked me the Latin name for an aspen tree and I didn’t know it? I discovered the group to be as diverse as plant life with one thing in common: everyone loved trees.

Our instructor and county extension agent, Jaydee Gunnell was witty, quick to make a pun, and down-to-earth, and inquired about each of our interests and goals. For me, that was learning to grow food like dad.

When you begin a MG class, you have a very narrow understanding of what you will learn. You may want to grow award-winning roses, maintain the perfect lawn, or learn methods for managing bugs. As I quickly learned, becoming a certified MG would require developing broad skills in soils, fertilizers, plant and insect identification, and irrigation. It would also necessitate 40 hours of community service where I would practice my newfound skills. While the class studied an array of information, each person ultimately developed a specialty. I assumed my role as the tree fruit guy.

Pruning

Dad always pruned his trees in February or early March. With Logan’s frigid winters I found this to be an unbearable time. However, Jaydee’s advice was simple and surefire: prune when the plants are dormant and plant sugars cached safely in their roots. This means that you never prune in a month whose name ends in “r.” He also shared a fundamental principle that changed my perspective on gardening forever. He explained that when we garden we aren’t farming peas and lentils, cherries, or plums. Gardening is about farming light. Suddenly the shape of my apple trees, pruned in v-shaped open vases made sense; they were giant light-collecting dishes.

USU Extension agent Jaydee Gunnell shows Josh Paulsen proper pruning techniques.

Jaydee instructed that every type of fruit tree needed to be pruned differently based on its species and age. After removing all diseased wood, a percentage of the tree is removed to encourage new growth. The key to peaches is to remove enough of the tree that you can throw a cat through it without hitting any branches—we followed the rule but spared our cat. By pruning accordingly, we could control both the structure and quantity of the fruit on the tree. Trees needed to be pruned every year, no exception. After practicing in our outdoor class lab, I confidently pruned dad’s trees, no finger-pointing needed.

Thinning

Logan had an extremely mild winter and spring in 2018. Our perfectly pruned trees produced a record number of blossoms. The wet and warm weather was also ideal for Fireblight, a bacterial pathogen incurable in apples and pears. Fortunately, the MG course taught me how to identify and treat it. I saved our trees, and as word got out about my training, I spent hours helping neighbors diagnose and treat theirs. Without a spring frost to knock-off the excess blossoms, the tree was quickly weighed down with quarter-sized fruit. The uneducated me would have left them on the tree, but the aspiring master gardener knew better.

Dad often taught me how to identify the king apple in a grouping. That apple would be spared while the three or four adjacent smaller apples removed. I always trusted his technique, but I didn’t understand its importance at the time. Like life, if we spread ourselves too thin, we end up with mediocre performance in all areas. I didn’t want mediocre fruit, I wanted big, juice and pie-worthy fruit, so I removed 75 percent of the fruit from the trees.

Caring

USU Extension purposefully takes a neutral stance on pesticide use—they teach Integrated Pest Management (IPM), a holistic approach to managing pests and diseases that incorporates natural, biological, and chemical controls to ensure healthy plants while limiting damage to the environment and sparing beneficial organisms. My apples were particularly susceptible to codling moths, which untreated led to wormy apples. Controlling the moth without pesticides is a chore and involves placing a paper bag over each apple which persists throughout the growing season—no thanks. Dad had historically paid someone to spray the trees, but I wanted the experience. The MG course taught me an array of controls, including those that were safe for bees, and instructed me on how to safely apply them. I joined USU’s Pest Alert system, which told me the exact time I needed to spray.

Herbicides are another controversial topic for master gardeners. For good reason, most of us, including myself, have misused them. Dad avoided them altogether, which I found extreme. The MG course forever changed my view of chemical controls. Glyphosate for example, the active ingredient in Round Up or Killzall, can be used in landscapes and vegetable gardens if applied according to the label. It will kill all plants on contact but is inert in soil. One experience during the course cemented the proper use of chemical controls—the time I almost killed Dad’s trees.

Apples from Paulsen’s orchard.

The fall before the MG course I purchased an extended control herbicide to remove the weeds that had popped up in Dad’s cobblestone path and patio. Dad always pried the roots out with a knife. The spray worked wonders and spared me hours of tedious digging. The following spring, while lounging in our backyard hammock, I looked up and noticed a bunch of dead limbs on a tree overhanging the patio. I stood and curiously inspected the trees throughout the yard. There was random limb die back on the River Birch in the front yard nearest the gravel path.

I went into panic mode. Weeks prior in our MG class we discussed the danger of soil sterilants. These ingredients were now being added to brand-name weed killers, much to the detriment of consumers who—because they didn’t read the labels—were applying these chemicals under the drip-lines of trees. Soil sterilants can be nasty in non-commercial applications because they remain active in the soil for years and kill plants by coming in contact with their roots. I scrambled to see if I could find the label of the herbicide I used that fall. I was horrified when I saw it contained trace amounts of the soil sterilant Imazapyr.

After the tears dried, I texted Jaydee: “I may have killed my dad’s trees. I need you to come look at them. I don’t know how I’m going to confront my mother-in-law.”

Extension specialists are too busy to make house calls, that’s what us master gardeners are for, but he made one for me. With his expert eye, he was able to rule out the soil sterilant as the cause. The dieback was likely due to a wound at the trunk and the River Birch had contracted a disease. The lesson remained: exercise care with chemicals and read the labels.

Enjoying

Our harvest the fall after my MG training was record-breaking. Mother nature deserves most of the credit, but the knowledge I gained also had a profound effect. We pressed 60 gallons of apple juice and had bushels remaining for fresh-eating, pies, and applesauce. The peach tree branches hung close to the ground dripping with enormous, juicy peaches. The plums fed our family and several herds of deer that frequented the yard.

We made grape juice, pesto, pickles, and canned enough tomatoes to make fresh sauces the coming year. Most importantly, the graft that dad started with me in 2016 finally took, and a new generation of master gardener was born. Dad’s books of fact sheets no longer intimidate me. The garden has ceased to be a chore and is now a laboratory for creating, experimenting, and learning.

To learn more about the Master Gardener program and sign up for classes, go to extension.usu.edu/

Abraham Johnson December 27, 2019

I have learned that the fruit garden needs a lot of activities. I want to grow apples in my own garden. This article helps me a lot.

Keep up the good posting.

Thanks