Every Shift

Twenty-one years of hard work have led to this.

That’s what senior Chris “Cudi”Cutshall kept telling himself. The normally packed barn of the George S. Eccles Ice Center in North Logan was nowhere near its 2,400-person capacity, but Cutshall understood. It was a Thursday night game the week before Thanksgiving. It wasn’t a rivalry game against another Utah team and one the Aggies were expected to win against the Northern Arizona IceJacks. (And they did, thanks to an assist from Cutshall in the final four minutes.)

But the night was special for Cutshall. It was the first of four games in four days that make up the annual Beehive Showcase. His family and friends from Alaska were waiting in the lobby for him to get cleaned up so they could head out to eat.

But they weren’t the only ones waiting.

Cutshall emerged from the locker room to see dozens of fans gathered in the lobby, waiting for a chance to shake No. 12’s hand. He smiled for pictures, flashing his trademark missing tooth. He signed autographs. He stood there for another 40 minutes while employees worked around him to clean up the rink before it would all repeat the next day. And he did it without showing an ounce of exhaustion or pain.

“I don’t want to be weeping, wishing I had more time.” – Chris Cutshall

The bursitis in his knee made it excruciating to stand for more than 15 minutes—especially after playing on the ice. He signed posters and shirts while his right hand and wrist throbbed. And he’d do it again. Every day, for the next four days.

Cutshall refused to miss a single game that weekend. He had to play. His dad and childhood best friends had come to town to watch him displace one of the top teams in the division. But it was more than that. Cutshall had to play because, after the American Collegiate Hockey Association Nationals in March, the 24-year-old senior may never play competitive hockey again.

“I’m preparing for that moment, for that last time I touch the ice as an Aggie,” says the 5-foot-7 Anchorage native. “I don’t want to be weeping, wishing I had more time.”

Freshman Shea Bryant couldn’t say the same. The first-year rookie was home in Menlo Park, California, watching his teammates through the TV as he recovered from emergency bypass surgery on a blood clot in his popliteal artery. He tried to convince doctors to let him play again, only to be told that if he continued playing competitive hockey, he’d be back in the hospital to have his right leg amputated within the next three years.

Chris Cutshall loves to play hockey. He needs to play hockey. He’s still figuring out the what after hockey? Photo courtesy of Debbie Cutshall.

Fighting the Odds

No one expected Cutshall to get this far. Not even his father, Jim.

“He was always the smallest one on the team,” he says. “But he always had the best work ethic, too.”

When his son was 11 years old, Jim took him to the doctor because he was always tired, always getting sick.

“He was a skinny thing,” Jim says. “I just thought he was growing, but the doctor was like, ‘You ever feed this kid?’”

Cutshall had diabetes. It had gone undiagnosed for so long his body was feeding on its own fat and muscle. He was hospitalized for a week as doctors fought to get his blood sugar under control. Jim slept on the floor by his bed every night.

The day Cutshall was released, still feeling miserable, was a hockey practice day. He insisted he needed to go.

“I probably shouldn’t have let him go, but he was convinced he needed to be there,” Jim says. “I still didn’t really know anything about blood sugar, or the highs and lows, or anything, so I just let him get dressed and skate off.”

But Cutshall was dead on his feet within a few minutes and skated back to the bench to talk to his dad. The coach, a former player for Alaska’s semi-pro team in Anchorage, went over.

“Coach, I’m sorry. I just got out of the hospital today. I just got diagnosed with diabetes. I was in bed for a week.” – Chris Cutshall

“Having a blow already?” he said. Cutshall looked up at him, and said “Coach, I’m sorry. I just got out of the hospital today. I just got diagnosed with diabetes. I was in bed for a week.”

He turned to Jim, who confirmed the story. A few weeks later, the coach told Jim how glad he was to have his son on the team. Over the years, many people would tell him how much they love his son and how special he is.

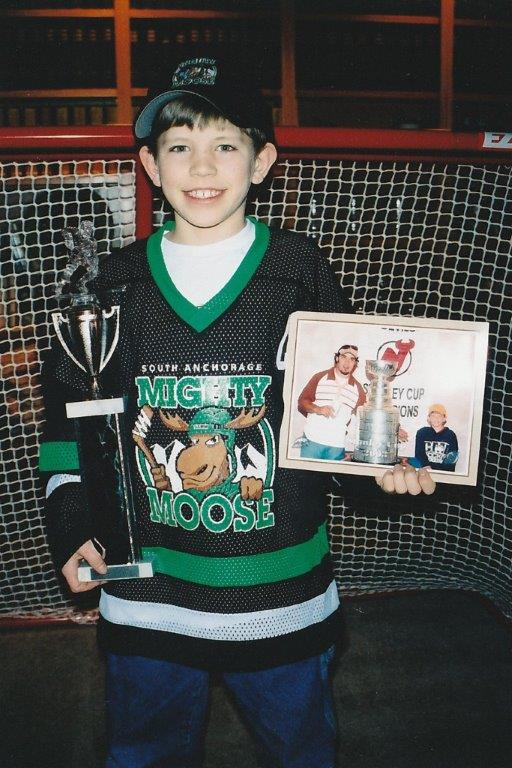

Chris Cutshall has been playing hockey since he was four. He’s found success despite typically being one of the smallest players on his teams. Photo courtesy of Debbie Cutshall.

But “special” and “destined for success” are two very different things. Jim told his son there would always be room on a team for the hardest working player, and it was advice Cutshall took to heart. “I just wanted to prove everyone wrong,” he says.

The Chance to Play

Bryant knows what it’s like to play through pain.

“Watching your team go into a game when you can’t help them is one of the most difficult feelings in the world,” he says.

While attending the prep school Gilmour Academy in Ohio, Bryant played 40 games before his hips gave out. He was diagnosed with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), often called ‘hockey hip,’ because it affects 1-in-4 players. It’s also highly treatable. With surgery, 90% of NHL players with FAI return to the game within one year and play at the same level as before.

While there was a small chance he wouldn’t skate again, Bryant was back on the ice in eight months.

But it was not his first bout with an injury. When he was in high school, Bryant began to feel overly sore in his right shin after practice.

“I just couldn’t pull my foot towards me or flex it at all. It was a challenge for skating because skating is really using your foot to flick off the ice and generate power,” he says.

Doctors found a blood clot in his popliteal artery caused by Popliteal Artery Entrapment Syndrome—a condition caused when an extra band of muscle compresses the artery. One week before his 16th birthday, Bryant watched, highly sedated, as doctors worked to punch the clot out to avoid bypass surgery. And when his doctor told him there was a chance he couldn’t play hockey, Bryant refused to believe him.

And when he had to have his hips operated on two years later, it also kickstarted his desire to play for a college team rather than taking a year or two off school to play in Juniors.

“I kind of realized after my hips blew up I was like, I really gotta put more effort into school, because you only go to school once, and you can play hockey the rest of your life,” Bryant says.

The Toll of the Game

In Logan, everyone wants to meet Cutshall’s dad. At one of the Beehive games, Jim went to get a hot dog between periods. He came back 20 minutes later, his food untouched.

“Long line?” asked one of Cutshall’s best friends, Max Kaercher. “Nope. But I think I just met all of Logan on the way back up here.” Jim replied.

The hard truth is that passion and hard work don’t often win out over size and speed. So Cutshall isn’t just another hockey player in this northern Utah town.

He is hope.

Whenever Cutshall was rejected, or a coach would underestimate his abilities, Cutshall would ask himself if it was the end of hockey. He’d pray for an answer, but until he got one, he’d keep playing. He wouldn’t slow down.

“He’s gritty,” Kaercher says. “Cutter’s one of those kids you love playing with, but hate playing against.”

“For me, it got to the point I decided I’d rather keep playing until I’m old. It’s not as competitive in the men’s leagues, but I’m not getting killed either. I hope Cutter sees that, sooner rather than later.” – Max Kaercher

Cutshall is the only one of his group of high school friends who still plays competitively.

“In my senior year, I only got about 10 minutes of ice time, and that was in the last game of the season,” Cutshall says. “But in that game, me and another kid in the same situation were the only ones to get goals.”

He and his dad wondered whether it was worth it to keep trying, but Jim says “doors just kept opening” for Cutshall. A former soccer coach bankrolled a trip to Vegas for a showcase. A coach from Europe at the tournament recruited Cutshall to play in Sweden. And when that fell through, former Utah State University hockey coach Jon Eccles was the first to call to offer him a place on the team in Logan.

“I miss it, I miss the brotherhood,” Kaercher reflects. “I always loved the competitiveness of hockey, but it really took a toll on my body with injuries.”

Jim says his son is at the same point. “For Chris, the passion’s never been stronger, but the body’s not healing anymore.”

Kaercher and the others nod.

“For me, it got to the point I decided I’d rather keep playing until I’m old,” Kaercher says. “It’s not as competitive in the men’s leagues, but I’m not getting killed either. I hope Cutter sees that, sooner rather than later.”

“He could barely get out of the chair after breakfast this morning,” Jim says. “The conversation was always, ‘how bad do you want it? What do we need to do to get there? Is it possible? So that when you leave, you leave it in your way.’”

Cutshall says those conversations have been instrumental in his outlook, “Every shift. That’s my motto. Every moment, take it in. So even when I’m hitting the ice the last time, I’m not thinking about what I’m losing, but looking at what I’ve created.”

The End

Freshman Shea Bryant had a choice: keep playing hockey or lose his leg. Photo by John DeVilbiss.

But the knowledge that his career was over blindsided Bryant.

He’d only been an Aggie for three months when he realized something was wrong. He’d been lifting weights and conditioning to build up his strength for the NCAA Division II team. His foot started aching.

“I’d be walking and think, ‘oh, it doesn’t feel right, like this kind of feels similar.’ I told my parents, but they said ‘it’s just in your head,’” Bryant says. “We literally thought that because the doctor said there’s no way for it to come back.”

Then over the next two weeks, the sensation spread up his calf. He flew home to see his doctor, expecting a two-week recovery time after the medical team removed the suspected clot—just like last time. But his muscles had grown so much that he had three clots, an aneurysm, and a damaged artery that could rupture at any minute.

“You can’t play hockey anymore. You can’t. You can ignore me and play behind my back, but I won’t be able to save your leg next time.” – Shea Bryant’s doctor

“You can’t play hockey anymore,” his doctor warned. “But what if I do?” asked the 19-year-old, who had spent the last 15 years of his life devoted to the sport. “You can’t. You can ignore me and play behind my back, but I won’t be able to save your leg next time.”

Bryant texted the team the news, and while his head understood the process, it didn’t feel real for months. He’d left Utah thinking the upcoming surgery would be a bump in the road, but it had turned into the end of the road.

But his Aggie friendships remain. Four months into life without competitive hockey, Bryant sees the team nearly every day. Just like on the ice, the veterans look out for the rookies.

“I had multiple shoulders to lean on,” Bryant says. “The support system made a world of a difference, because it’s made me feel like I’m not alone.”

The day after the showcase, Cutshall was back at the ice rink to keep score for the rec leagues. He didn’t joke with the refs or chirp at his former teammates like he had the week before. He huddled at the scorekeeping desk as he sipped Gatorade and tried to get up the motivation to open his laptop and work on the homework he’d neglected all weekend.

He made two airport runs to Salt Lake City in 12 hours. And he wasn’t looking forward to driving in more holiday traffic for Thanksgiving two days later.

Cutshall was worn down.

Chris Cutshall plays his final game as an Aggie. Photo by John DeVilbiss.

“It hit me when I got to the airport, sending my dad through security was the closure on my last Beehive,” he says. “I didn’t want to leave, or for him to go, because it makes it 100% official.”

“The biggest thing is just making sure they understand that you’re looking out for their best interests and making sure that they realize the risk, realize the reasons why they’re getting pulled out … that it’s not only for their health for right now, but for the future.” – Kendra Gilmore

“Every year. I’ve played competitive hockey for the last 21 years,” he says. “How do you cope when everything you’ve done comes to an end?”

As a sport psychology professor and consultant for USU athletics, this is a problem Richard Gordin knows well. He says the emotions an athlete goes through when they’re near the end of their career are not dissimilar from the five stages of grief.

“They’re going to have emotional upheaval once the athlete realizes it,” Gordin says. “When they become aware or they’re seriously injured, their emotional state can vacillate seriously, and they can feel disconnected, shock, self-pity.”

Gordin says there are four main ways an athletic career can end: an athlete can be cut from the team, they can age-out, freely choose to stop, and—most commonly—they can suffer a career-ending injury.

Cutshall’s situation is a blend of the latter three. His right hand hasn’t been the same since he broke five bones in it in January. This spring, he is scheduled to undergo two surgeries on his elbows to repair damage on both his median and ulnar nerves.

“I’m already hurting, and the surgeries may make the choice for me,” Cutshall says. “With nerves, you never know how they will heal, so I may not be able to handle a stick after that.”

Before It’s Gone

“Athletes can suffer identity loss if they can’t play anymore, and when the sport’s been a big part of their life, it’s even harder in those people,” Gordin says. “They can experience fear and anxiety on whether they’ll recover, or where they’ll be in the lineup if they do come back. It’s quite a complicated area.”

And it’s complicated even more by athletes choosing to play through injuries.

After overextending his elbow and fracturing the head of his radius at Gilmour, Bryant’s doctor advised him to wait a few weeks before playing. Bryant responded: “I’m playing, whether you clear me or not, because in USA Hockey, I know that you only need a doctor’s clearance for concussions.”

Kendra Gilmore, USU’s athletic club trainer, says that over the three years she’s been the athletic trainer at USU, more and more players feel comfortable sharing with her that they’re injured.

Many athletes want to push through and will fight through a little bit of pain to play, she says “but obviously, with more serious issues like concussions, there’s a whole return to play protocol that they have to go through.”

Shea Bryant’s health forced him to give up playing competitive hockey. But he can still fly across the ice. Photo by John DeVilbiss.

Telling an athlete they need to end their career, even if it’s for their health, is one of the worst parts of her job. And she’s had to do it multiple times this year.

“The biggest thing is just making sure they understand that you’re looking out for their best interests and making sure that they realize the risk, realize the reasons why they’re getting pulled out,” Gilmore says. “And that it’s not only for their health for right now, but for the future. And that was a big thing with this year, talking about how 20 years down the road, we want you to feel normal, we want you to feel healthy, and be able to do your daily activities.”

But that can be a hard message to swallow when playing sports has been your life until that point.

Jim says growing up in Alaska makes it hard to see life beyond hockey.

“It’s supposed to be fun, especially when they’re young,” Jim says. “I try to tell all the parents who come up to me that it’s not life or death. One day they won’t want to play anymore, and that’s fine. Life’s more than hockey. But I don’t know if they listen.”

His own son continues to struggle with this. In Cutshall’s spare time, he volunteer coaches for the valley’s U12s, and he gives private skating and hockey lessons. Even on nights when he’s working as a scorekeeper for the rec games at the rink, he makes time to do the team’s laundry so it’s fresh for game days.

“I had multiple shoulders to lean on. The support system made a world of a difference, because it’s made me feel like I’m not alone.” – Shea Bryant

Alison Meifert, USU’s team manager, says no one on the team spends more time at the Eccles Ice Center than Cutshall. “He literally doesn’t do anything else. If he’s not at school, he’s at the rink.”

His roommates say “he’s never home.”

But Cutshall doesn’t see it that way. Because, to him, hockey is home.

The shattered teeth, the 3rd-degree tear in his olecranon joint, the bursitis, the carpal tunnel, the tight hip flexors—it all adds up, but it doesn’t matter. Because his time at USU has an expiration date.

“I’ll stay late and do the team’s laundry, or I’ll hang fliers in the freezing cold until midnight, but I’m not gonna hate it,” he says. “Because one day, I won’t be here, and even these nights are ones I’m gonna miss.”

That’s why he plays like he’s fighting for a spot in the next stage, even though he knows he’s probably not.

Every shift.

Every moment.

Before it’s gone