The Lara Project: Unraveling the Universe

Theoretical physicist Lara Anderson ’03, M.S. ’04 is flying.

Her mind and ballpoint pen are moving at what seem to be the speed of light.

A blustery November day finds this Rhodes Scholar and associate professor at Virginia Tech teaching in the sleek metal and glass New Classroom Building, tearing

through equation after equation related to coupled oscillation on an overhead projector.

“The game plan is we’re going to try to plug in z, which I’m going to define as the set of coefficients A1, A2, e to the i omega t,” says Anderson to the assembled juniors and seniors. “Write that as a vector — e to the i omega t. I want to plug that into my matrix equation, and x double dot is minus k x.”

Some people have big ambitions. Anderson’s are small. Super small. Her field of interest — string theory — burrows the mind down to the most infinitesimally minute iotas of reality. It holds the promise of unifying incompatibilities between Einstein’s theory of General Relativity and quantum mechanics in a framework that governs all forces and all matter.

As Anderson tells it, one-dimensional strings, not atoms, are nature’s fundamental building blocks. They are a millionth of a billionth of a billionth of a billionth of a centimeter long, so tiny that if an atom were enlarged to the size of our solar system, a string would be as tall as a telephone pole.

One more thing — strings are weird. Imagine an ultrasubmicroscopic party hosted by Timothy Leary, narrated by Dr. Seuss, and drawn by M.C. Escher. Strings can be matter or energy, depending on how furiously they vibrate. Strings nestle inside other small thingamajigs — shapeshifting donutoidal entities called Calabi-Yau manifolds. These have dimensions beyond length, width, and depth. Maybe 10. Maybe more. It is all unimaginably unimaginable — at least to the minds of non-physicists.

“String theory miraculously overcomes 100-year-old problems of quantum gravity,” says Anderson, who, not surprisingly, was class valedictorian. “The catch is we don’t know if that’s actually a theory of our universe. It has incredible mathematical consistency. It has proved itself to be very able to shed very deep insight not only into physics but into mathematics. But we don’t know yet in a verifiable way if that’s really the physics that we’re going to see in nature. We don’t know if this is how nature really works.”

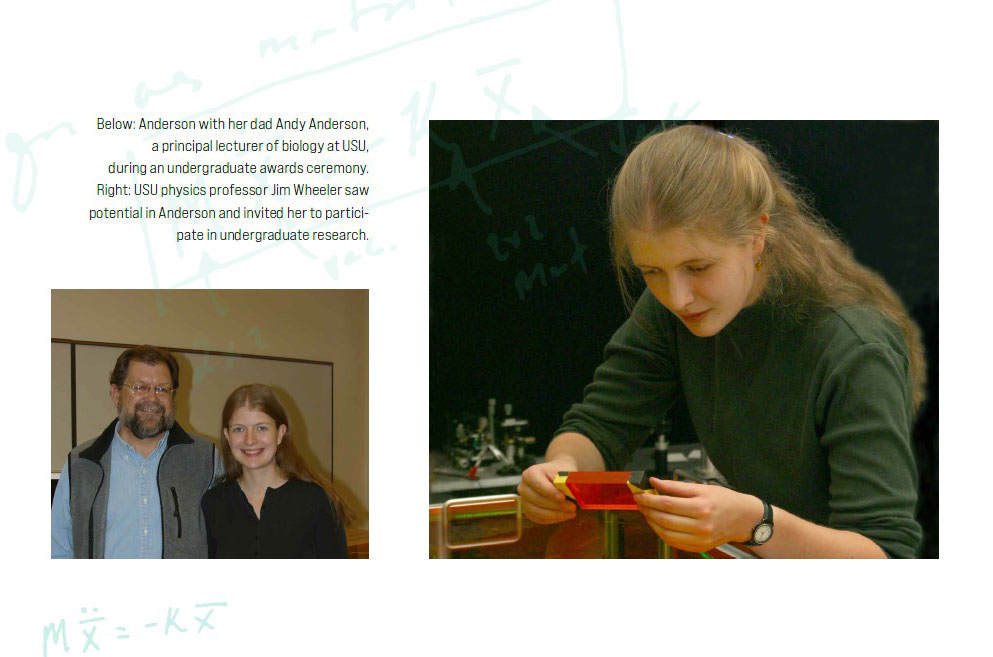

Anderson, who was home-schooled and is the daughter of Andy Anderson, principal lecturer of biology, is one of those people who excels at almost everything. She holds black belts in Kempo Karate and Aikido. She plays Bach on the violin. (But her favorite piece is Schubert’s Ave Maria.) She makes furniture. (“It’s been a fun opportunity to get lots of power tools,” she says.) She gardens, growing plants and vegetables from heirloom seeds. (“I like being able to take things apart at a detailed level. The mechanistic ‘take it apart — put it back together’ is appealing,” she muses.)

When asked what she is not good at, she replies, “I’m terrible at lots of things I don’t find important — appearances, video games, bowling. The list is long.” Singling out time management as her chief bugaboo, she confesses, “I’m always over-optimistically committing to too many things.”

Most of all, for someone so otherworldly smart, Anderson is down-to-earth. She cuts a low-key profile. If the Einsteinian stereotype of a male physicist brings to mind an image of a zany-haired, disheveled gent who jostles chalk in the pockets of his suede-elbowed tweed jacket, she sports a dark T-shirt, jeans, and a black leather jacket around campus.

“If there were international rock stars of science, that would not be me, but I’m proud of the work I’m doing,” she says. “I’m productive. I’m in there pitching, as it were.”

Her string theory colleague Washington Taylor, a professor of physics at the MIT Center for Theoretical Physics, begs to differ. “In the subfields of string phenomenology and string geometry, Lara is one of the top people in the U.S. and worldwide. She’s one of the people making the most interesting and exciting advances,” he says.

Anderson’s life changed the day her parents took her to Salt Lake City’s Hansen Planetarium (now the Clark Planetarium). She was 12, and she didn’t know what physics was. Stephen Hawking designed that day’s star show. It was about the history of the universe — the Big Bang, the expansion of the universe, and black holes.

“I watched this story of how people could figure out things about the universe just by thinking about them. It was so beautiful and amazing,” she recalls. “I walked out wanting to be a physicist. Of course, I had no idea what that meant, but I loved the ideas. I loved those big, beautiful, sexy ideas.”

Fast forward to her first year at Utah State, where physics professor Jim Wheeler saw potential bursting from her like high-energy photons from a star about to go supernova. Soon she worked as his unofficial research assistant as many as 20 hours a week, helping him write papers on such things as supersymmetric gravity theory, a field beyond the grasp of many grad students.

When Wheeler applied for a grant based on that research and listed her as a colleague, one of the decisionmakers chastised him, saying, “You can’t teach an undergraduate supersymmetry.”

“It had already been done,” says Wheeler with a chuckle. The head of physics department noticed his tutelage of the precocious Anderson and dubbed their relationship “The Lara Project.”

Looking back, Anderson says, “He took a wild gamble. Being a professor now myself, it was a little crazy for him to throw all that work at an undergrad, but it was amazing.” As if that were not enough extracurricular activity, she spent three years developing a mini-controller system for a physics department experiment on how water boils in zero-gravity. It flew in 2001 aboard Space Shuttle Endeavor.

“It was exciting to send my fingerprints into space,” says Anderson.

Contrary to stereotypes, theoretical physicists do not spend their days in solitude thinking deep thoughts. Besides teaching, writing code, and doing computer modeling and programming, Anderson collaborates with international colleagues.

She travels. A lot. The first year of her son’s life he flew with her 100 times to academic events. When she learned that Virginia Tech did not allow childcare as a research trip expense, she lobbied the provost and president and won a change in the policy.

Anderson never had a female physics professor when she was in college, and she estimates that of all physicists in the world studying high-energy particles, fewer than 5% are female. She would like that to change. Toward that end, she chairs her College of Science’s committee for diversity and inclusion, and she recently organized an American Physical Society conference for undergraduate women in physics on campus.

“The sort of white male homogeneity of the field is to its detriment,” she says. “People who think differently are really valuable. It’s self-perceived that you have to be super-smart to get into this, and that’s definitely a deterrent, because a lot of women and minorities haven’t been raised with the confidence that they could do this. That’s something I’ve worked to try and dispel. This is like any other job. It’s just a question of getting in there, pitching, and trying it piece-by-piece as required. Being a super genius — not required, okay?”

But perseverance helps. In her 2003 commencement address, Anderson summarized what she learned at Utah State: “Work on the hard stuff. Be devoted to the truth. You know more than you think you do. Just try.”

A sign on her office door titled “Stress Reduction Kit” testifies to the difficulty of her work. The kit consists of a circle in which the words “BANG HEAD HERE” are written.

Underneath the instructions one reads: “Repeat as necessary or until unconscious.” Though hundreds of the world’s physicists are trying to unravel string theory’s mysteries, no breakthroughs may come soon. Undaunted, Anderson tells an anecdote about Michael Faraday, a pioneer in the field of electromagnetism: “Back in the 1800s he did a demo for the Royal Society in London. A member of parliament in the audience asked, ‘This is all very pretty, but what is this going to be good for?’ Faraday famously answered, ‘Sir, I do not know, but someday you will tax it.’”

Her belief that string theory could revolutionize life keeps her going. “Every time we have discovered new fundamental interactions in nature, there have been tremendous practical consequences — whether that’s through semiconductors and modern computers or atomic energy,” she says.

But Anderson has found one problem associated with the study of string theory — being a theoretical physicist is a conversation killer. “I can definitely say that saying you’re a particle physicist is not cool at parties. Jazz pianist goes down much better,” she explains. “I have an Egyptologist friend. That goes down really well. People like talking about mummies much more.”

By George Spencer

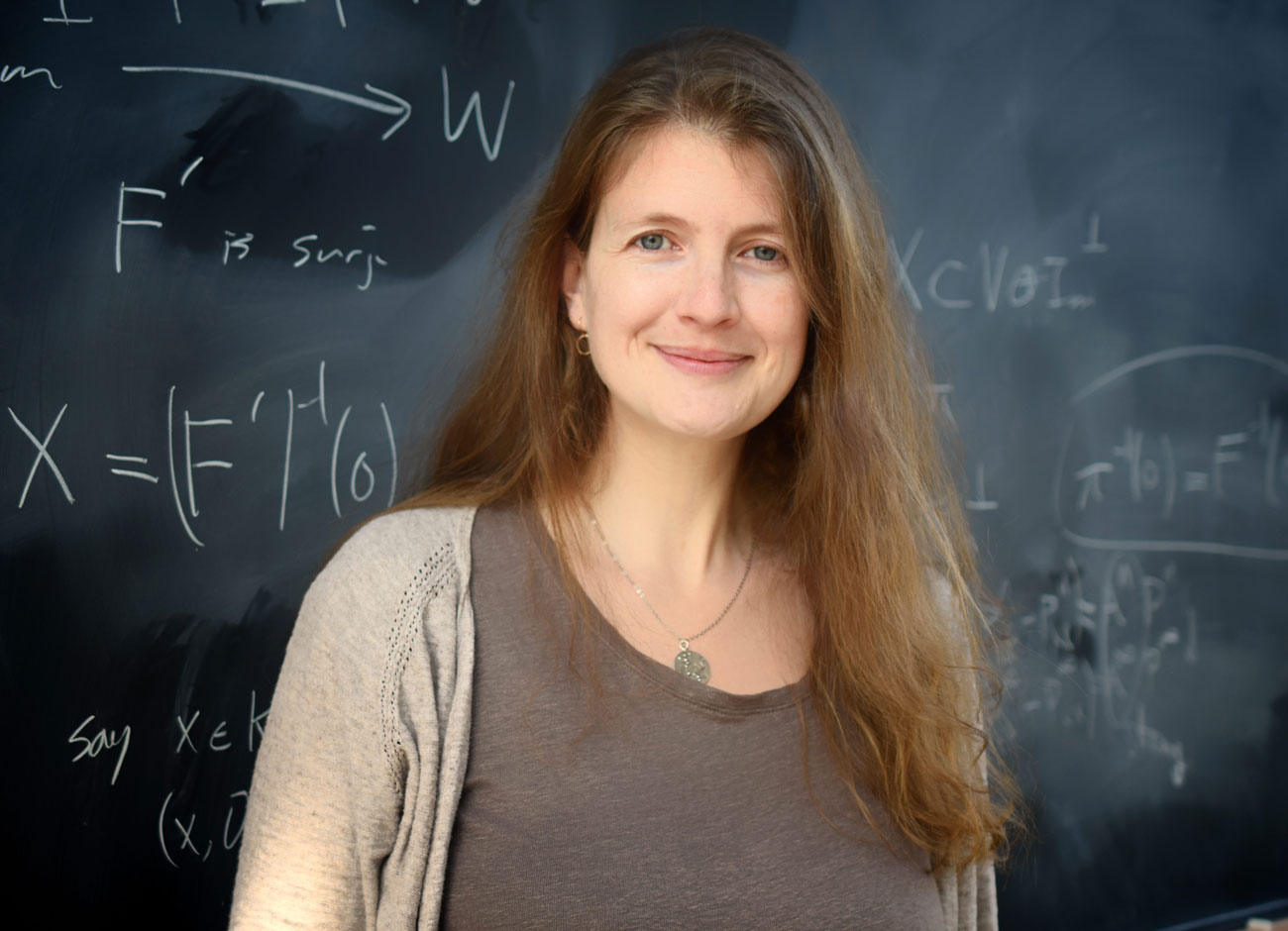

Opening photo of Lara by Laura Schaposnik.