The Fight For Disability Rights Goes Online

COVID-19 upended the planet. Suddenly everything happened on-screen and in cars.

But for those with disabilities, the rush online made some things hard and other things impossible: learning, working, buying food, signing up for a vaccine appointment. People who have difficulty reading print often rely on screen reading technology to access web content — but not all websites are designed with screen readers in mind. When COVID hit, websites were a mixed bag. Some were accessible. Some were not. And a lot of untrained new players rushed in.

“It was horrendous,” says Cyndi Rowland, director and founder of the Web Accessibility In Mind project (WebAIM) at Utah State University. “A lot of folks understood. They were patient, they used other mechanisms, like getting family members to help them. But then as the pandemic went on, and went on, and certainly now that we’re getting out of it, their patience is gone.”

That’s not just a gut feeling. Lawsuits targeting inaccessible web sites are on the rise, up 15% from 2020 to 2021, according to usable.net. On average, 10 cases regarding poor web and app accessibility are filed per day in the United States.

Over the last 22 years, WebAIM has trained web developers and administrators, with the goal of helping people with disabilities access information and have a good experience online. The project, located within the Institute for Disability Research, Policy & Practice, has grown steadily. So has the web — and the number of untrained developers. Throw in other, built-world accessibility issues like transportation, and life becomes exponentially harder for people with disabilities. Pre-COVID, if a store’s website or app was unusable, the blind could still take the bus to a grocery store. In 2020, all of that changed.

“For the first few weeks, it was really problematic,” says Everette Bacon, a blind assistive technology specialist for the Utah State Division for the Blind and Visually Impaired. “They had a lockdown for everywhere, except grocery stores. But grocery stores were limiting when people could come in, and there were no employees. So, you couldn’t get an attendant to get around the grocery store. You had to pretty much go to online ordering.

“And then they wanted to deliver it to you outside the grocery store. Well, you need a car for that. Blind people don’t have cars.” Even worse, public transportation ran on a reduced schedule, and many people hesitated to use it.

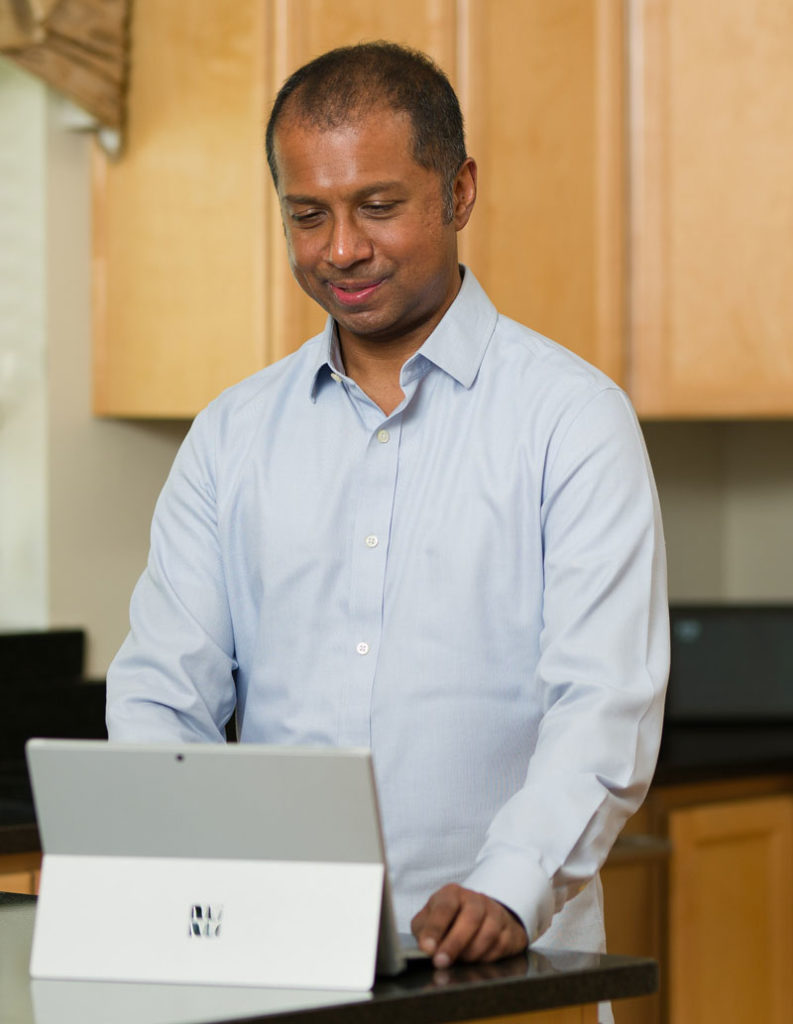

Sachin Pavithran Ph.D. ’12, executive director of the US Access Board, went into the pandemic tech savvy. He is blind and the former policy director of USU’s Institute for Disability. But sometimes, knowing which platforms to use still didn’t help. “If you tried to order through Whole Foods, there were no [grocery pickup] slots available,” he says. “So you had to go to another online store to get it, but that still might not be accessible.”

Bacon had similar experiences.

“If you didn’t get that spot you were just out of luck,” he says. “You had to wait till the next day. And if you needed something immediately, that’s problematic. … I was fortunate because I’m married to a sighted person. But I did know of blind individuals in Salt Lake City and some of the rural areas that were in a desperate situation.”

COVID became a time-sucking obstacle course. School and work moved online, but websites and even emailed PDF documents were not accessible. These bumps in the road always existed, but they multiplied, while the in-person workaround options disappeared.

WebAIM works on digital accessibility, and it helped make the pandemic more bearable by swelling the ranks of web designers and developers who take accessibility seriously. Many of WebAIM’s former trainees were and are employed by today’s tech giants.

“In most all of the trainings that we’re doing of late, we almost always have participants from Fortune 100 corporations,” says Jared Smith, WebAIM’s associate director.

And there is good news. COVID brought telecommuting into the mainstream. People with disabilities had sought the option to work from home for many years. When it became a widespread requirement, employers couldn’t deny them that option anymore.

And there were improvements in the digital world. Early into the COVID era, platforms like Google and Microsoft began offering or expanding the availability of captioning — another important accessibility feature — to their videoconferencing programs. Some shopping platforms truly did work for users with disabilities. WebAIM data shows government and educational websites in general have improved their accessibility over the years. Content management systems, including the one used by Utah State University, now require some elements of accessibility to be added by content managers who don’t do HTML code. A good example is alternate text for photos.

In the latest WebAIM Million evaluation, which analyzes the home pages of the top one million web sites for accessibility around the world, errors actually fell very slightly between 2021 and 2022. The bad news: there were still 50.8 detectable errors per homepage on average.

When so many entities suddenly conducted their business virtually, a lot of content was simply thrown out there, beyond the reach of some users. To cite just one example of bad accessibility: imagine needing to fill out an online form, but it has no identifiable form labels. Where do you put your name? Is that other blank for the city, the state, or the ZIP code?

Bacon and Pavithran agree that accessing COVID testing information on websites was spotty — and once again, the in-person work-arounds didn’t make a lot of sense. Bacon had to sign up for testing over the phone, after many phone calls and transfers of calls. The actual testing mostly happened in a drive-through. “I remember speaking with the mayor’s office here in Salt Lake City,” Bacon recalls. “Salt Lake City came around and said, ‘Yeah, this this problem,’ So they actually worked it out where sometimes they would they would bring a testing kit to you at your home.”

Pavithran says neither in-home test instructions nor its results were readable. Blind people who did not have a family member to help had to ask for someone to come in and perform a COVID test. Potentially, both the tester and the testee were exposed to an increased risk. “The whole point of in-home testing was useless.”

When the vaccine came out, web users with disabilities struggled to make an appointment. WebAIM and Kaiser Health News teamed up on a study of 94 state websites around the nation that offered information about the vaccine, providers, and sign-up forms. All but 13 had accessibility barriers.

That was the reality for Bacon, who was unable to sign up online with a private vaccine provider. “You had to go there [to the provider’s location], and you had to fill out a form to get your vaccine. If you didn’t go with a sighted person, there was nobody there to help you fill out that form.” That was the case even when he received his booster at the end of 2021.

Clearly, the time has come for a better user experience for people with disabilities. And that is WebAIM’s next big push, combining existing tools and evaluation with massive data the WebAIM team has collected over the last few years.

WebAIM Million data will now help WebAIM assign a usability score to entities that want to know how they compare to other websites when it comes to accessibility. That score, called the Accessibility Impact or AIM Score, also includes some manual evaluation. For a quick view of the automated web accessibility checker, try WebAIM’s WAVE tool for yourself. (Note: many accessibility errors cannot be detected by an automated tool, but a good WAVE result is usually a good indicator of the website’s attention to accessibility.)

And yet, for all the focus on web accessibility, Pavithran cautions against an unintended consequence: Losing sight of accessibility outside of the digital space. Disability advocates started their fight for social justice in the built world, advocating for ramps, elevators, better public transportation, and the removal of those physical barriers that kept people with disabilities away from their communities. The Americans with Disabilities Act helped change that. What if an accessible virtual world is perceived as a way to avoid the barriers of the physical one? Would the disability community’s concerns about access and transportation end up dismissed because they could always work and shop from home?

“I think what we’ve learned in the virtual environment is great, but I think we need to be careful in the conversation around disability rights and disability access … that it’s not a substitute to address the issue,” Pavithran says. “My worry is, if people with disabilities keep opting to do the virtual component as a way to not have to have to deal with a transportation barrier, what happens in the future?

“Before the ADA, people with disabilities were not as visible in the community. And we don’t want to go back to where we were before.”