Army Meets the Academies

Driving south on Main Street in Logan, I passed the industrial tool supply store.

There, perched above the commercial hubbub, was a solitary, soft blue billboard. Its color mimicked that of the afternoon sky and its deep blue letters seemed to float in mid-air: For some, feeling LEFT OUT lasts more than a moment.

As I read the words out loud, I felt them in my gut; I tossed them around in my head, like a juggler in a circus ring, for the rest of my drive. The message struck a deep chord, and for a time I lost interest in where I was going. Instead, I considered how the feeling of being left out, of not belonging, is so uniquely human. It’s an emotion that each of us experiences throughout our lives; an emotion that, if left unchecked, can profoundly influence our life paths and personal choices. I’ve consistently fought to overcome this feeling throughout most of my professional life.

Performance as Belonging

In 1975, when I was 10 years old, President Gerald R. Ford signed Public Law 94-1065. This law—for the first time in our nation’s history—allowed qualified female candidates to attend, what had historically been the all-male federally-funded service academies. The first women entered the service academies in the summer of 1976. The Class of 1980 became the first to graduate and commission women as officers in the U.S. Armed Forces.

In 1982, by mid-senior year in high school, I had been accepted to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Without much hesitation, I entered the academy in July 1983 as a member of the Class of 1987, “Our Country We Strengthen.” Our class became the 185th class to induct men into the Corps of Cadets, and the eighth class to accept women.

People often ask about the difficulty of being “one of the first women” at West Point. These questions are always a bit embarrassing; I explain how it was much more difficult for women inducted into the academies during those first four years. They endured indignities and hardships that live on in academy folklore. As retired Navy Commander Janie L. Mines, the first and only Black woman admitted to the Naval Academy in 1976, gently explained, ”It just happened quickly, and it needed to be done. [But] the academies weren’t ready [for women].”

While the successes of the first women proved—to the public and to the academies—that women could survive service academy life; women’s acceptance at the academies was still up for debate. The service academies, as military colleges that prepare officers to lead in combat, fulfill a unique mission among U.S. institutions of higher education. In 1983, women were still prohibited from filling combat roles in the U.S. military, and men argued that academy slots were wasted on women. Underlying these arguments was the general disbelief that women could lead military men, in or out of combat.

Such was the scene as my parents dropped me off in July 1983: Women were at the academies to stay, and many men had not accepted it. Our class bonded during summer field training and I started first year academics feeling a strong sense of esprit de corps and shared purpose with my classmates.

As naïve as it sounds, I had yet to understand that there were people who considered women’s abilities and societal roles to be different than men. As my class integrated with the upperclassmen and faculty, I started to perceive, and to detect, those who didn’t accept me because I was a woman cadet. While caution and recognition were approaches used to avoid embarrassment and hostility, I knew I was powerless to advocate for myself and had nowhere to hide. The constant potential to be cast out because of my gender ignited my competitive spirit, and perhaps even a subconscious need to excel— regardless of the nature of the task or the personal cost. Over the next four years, I came to wield outstanding performance as both superpower and shield: If I relentlessly performed, task after task and day after day, it would be impossible for others to justifiably claim that I didn’t belong.

Interdependence as Belonging

Aviation became a branch of the Army the year I graduated, and the Class of 1987 became the first class to receive aviation slots during commissioning. Prior, those trained to fly for the Army were men selected from the ranks of combat arms branches where women did not (yet) serve. Since branch slots were filled in order of academy class rank, a few of us women were able to choose aviation as our branch when our numbers were called.

If I learned one thing at the academy it was this: Being unquestionably capable makes everything easier. This lesson continued to serve me at a time when there were few women training to become U.S. Army helicopter pilots. Having graduated with a mechanical engineering degree from a program that emphasized aerospace applications, the ground school portion of flight school came relatively easy. Flight training proved more challenging, particularly because it was hard not to feel conspicuous on the flight line. It was clear that the influx of women pilot trainees was on everyone’s radar. During basic combat skills flight training, I flew with a stick buddy who began getting ill during our low-level training flights. While he eventually overcame the condition and graduated, several peers began a rumor that the motion sickness was caused by my (lack of) combat flying skills. Luckily for me, I had check ride scores that showed otherwise.

As I completed advanced combat skills flight training my instructor pilot— who compensated for his small stature through sheer intensity—unexpectedly took me aside. He leaned toward me as if telling me a secret, and said, “Always remember, your knowledge is your power.” He looked at me intently, as if watching his words sink into my skin. He made his point clearly: I was going to judged more harshly, as a woman, than the men pilots in my unit. “You have to be better.” I nodded, feeling a sense of gratitude for finally hearing someone say it out loud.

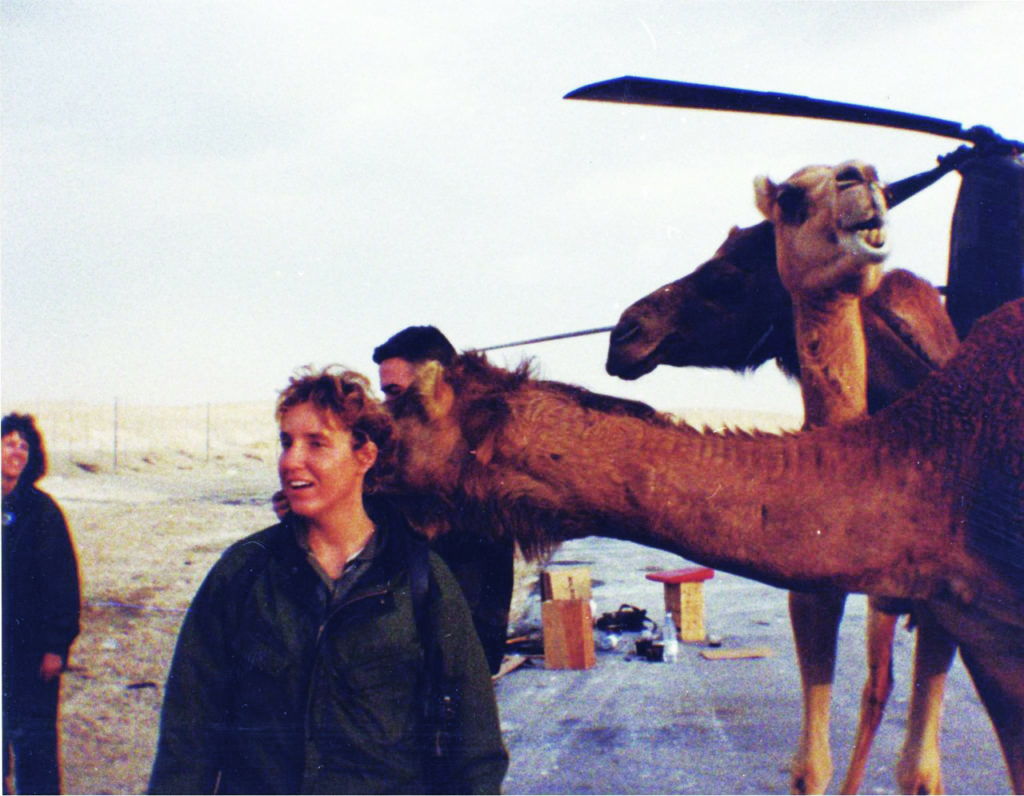

I carried these words with me to my first unit assignment in South Korea. At the time, I didn’t know I was the first woman officer and pilot assigned to the unit. I endured an uneasy month waiting to take my induction check fully aware that my reputation hinged on the results of the ride.

Afterward, I was quickly integrated into the training mission schedule. For my first mission, I was assigned as co-pilot for a pilot-in-command who likely had more hours in a CH-47 than I had breathing. For two days, sunup to sundown, we flew construction materials from the base of a mountain to its peak. The materials, the size and shape of telephone poles, were attached—one at a time—using a 100-foot-long sling to a cargo hook located on the belly of our helicopter. Each time we reached the mountain peak, we hovered more than 100 feet above the landing zone. There, our job was to gently lower the pole into position, holding it steady while workers physically secured it, upright, on the ground.

It was the most challenging flying of my young aviation career. Although the inherent danger was obvious, we flew as a team, alternating roles of flying and systems monitoring, while the crew-chief verbally guided the pinpoint pole placement as he hung his torso upside down out the cargo hole in the floor of the aircraft. Each time I accepted control of the aircraft, the crew was depending on me—not only with mission accomplishment, but also with a $12 million aircraft and their own well-being. When we arrived back at the unit, the operations officer was there waiting, overly eager to find out how the mission had gone. “How’d it go?” he asked, scanning our expressions one by one. Lighting a cigarette and taking a long draw, the pilot said “No complaints” as he gave an ever so slight smile in my direction.

Building as Belonging

Although it seems funny now, there was a time when I thought I’d always be a helicopter pilot. Yet, after serving past my academy commitment and through the First Gulf War, I decided to end my active-duty service in 1994. Admittedly, I was nervous about reinventing myself as a civilian. A common question that service members ask those who decide to leave the service is: “What are you going to do?” Deciding to stick with something I knew, I enrolled in a graduate program in mechanical engineering. After graduating with a master’s, I accepted a job and moved across the country, eager to begin a new career working as a mechanical engineer on a well-established and profitable product line within a major American technology company.

As I walked into the office on my first day, it was if I had arrived late to the party during cleanup the morning after. I was met with quizzical looks and empty cubicles as the company was in the process of consolidating two divisions. Amid the uncertainty, my manager was unable to assign new project tasks; I had a job, but nothing to do and no role to fill. The state of limbo continued for several months until one-day my manager called to tell me what I already knew: my position was no longer needed, and I was being let go. Disappointed yet relieved, I applied for several open positions and traveled to job interviews as the reorganization moved forward without me.

Eight months after first arriving in San Diego, I left for Colorado. As I walked into the office on my first day, it was if I had arrived early to a party that was still being planned. I was met with eager smiles and a buzz of activity. The company was forming a new design and development group and I was the second mechanical engineer hired. The first had been my manager. I had job, and my pick of tasks to take on and any number of roles to fill. For my first official task, I served as a technical writer, helping to complete and edit the group’s first product design proposal. Everyone was thrilled with my work and it reminded me of how much I loved to write. The positive energy continued, and with each new role I took on came new experiences, new knowledge, and the satisfaction of helping to build a team.

Authenticity as Belonging

In 2005, I started to move away from a conventional, full-time career path. At first, the shift wasn’t a conscious one; I was engaging in new opportunities, such as teaching, that piqued my interest and seemed challenging and socially relevant. In 2009, I accepted full-time employment as an engineering instructor at Utah State University. In this role, I taught undergraduate courses in the evenings to working adults and other nontraditional students.

Teaching these students opened my eyes to the disparate ways that American citizens experience education. Today, most do not start their college education immediately after high school, at age 18, with tuition, housing, and sustenance costs paid for by someone else. While I have always had the privilege of being able to focus on my education, most in this country do not have the financial resources or social capital needed to devote all their efforts and energy to their education.

It was my interactions with one engineering student in particular, a bright-eyed and energetic jet engine mechanic Air Force veteran who continued to serve in the reserves while attending school, that helped reconnect me to my military past. This was a history and an identity I had learned to bury and hide from while a graduate student at a top 10 engineering graduate program directly after leaving the Army. While there, the unsolicited attitudes and comments about my academic preparation and readiness convinced me that I was not Ph.D. material and shaped my plan to leave graduate school as soon as possible for an industry position.

More than 10 years after earning my master’s, the experiences I had teaching nontraditional and military-affiliated students set me on a path of self-reflection and recognition that ultimately led me to where I am today: an assistant professor of engineering education. Inspired by the sense of purpose and dogged persistence of these nontraditional students, I decided to pursue a doctorate in engineering education—a new offering at Utah State. Working more from a hunch than a plan, I enrolled part-time and continued to work as an instructor while earning my degree.

My dissertation research focused on examining the experiences of the working adult and nontraditional students I taught while receiving my doctorate. My current work, funded by a five-year, $568,000 National Science Foundation Early Career Development grant, focuses on exploring the experiences of military-connected engineering students and developing new understandings of the institutional and structural changes that are needed to effectively support and retain talented, trained, and professionally experienced undergraduates. In a sense I have come full circle. I have fashioned a new career and a new purpose wherein I can authentically embody, and put to good use, the variety of identities that make me who I am.