A Space For Everyone

Parks and other outdoor, public spaces are not just places where people connect with the environment and each other.

Like all built landscapes, they are physical manifestations of the attitudes, perceptions, and values of the people who create them. The problem is that often the creators don’t fully consider how people who are different from themselves might want to use the space.

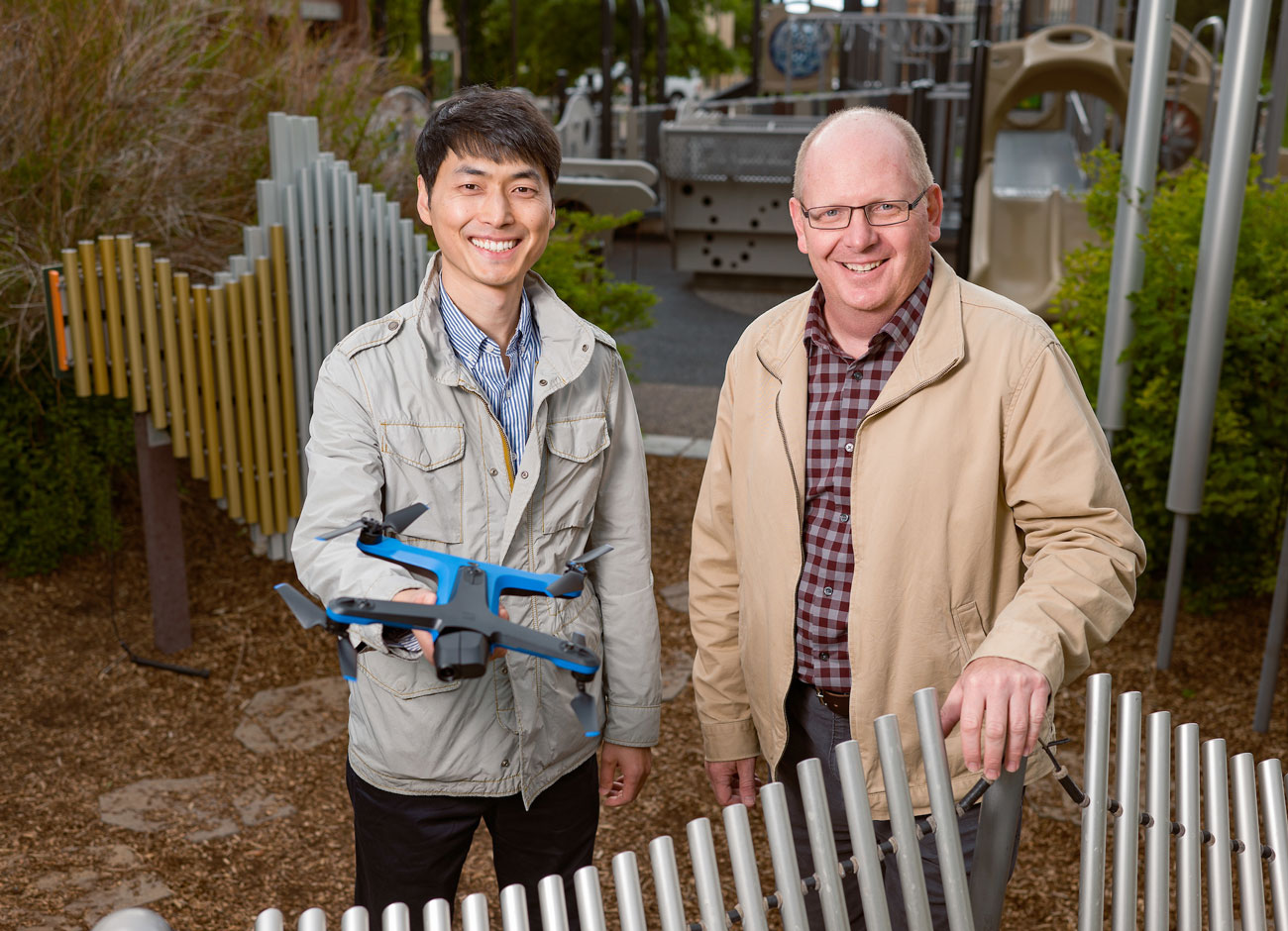

Seeking to understand and design inclusive public spaces is the focus of work by Keith Christensen, head of USU’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning, and Keunhyun Park, a co-director of the department’s Visualization, Instrumentation, and Virtual Interaction Design Laboratory. Each professor studies different aspects of creating spaces that are inviting and inclusive, clarifying what those concepts mean to different groups, and how people use (and don’t use) existing spaces.

The following conversation about how public spaces can help or hinder feelings of belonging has been lightly edited for length.

Lynnette Harris: There are many different aspects of landscape architecture. Why is this topic especially interesting to you?

Keunhyun Park: Initially I was intrigued with designing pretty spaces. But when I worked as an auxiliary firefighter as part of my South Korean military service, my job was to register and care for low-income, single, older adults in the district. I witnessed environmental injustice issues where economically disadvantaged people were more exposed to environmentally disadvantaging circumstances. That began changing my views of society and that people may not have some personal characteristics, like being lazy or other things, but that there are ways that environments affect connection and worsen economic hardship. I wanted to understand how to create more just, sustainable, and healthy places. I’ve researched the distribution of public spaces and whether they are accessible to all people in terms of gender, race, ethnicity, income level, age, and found a lot of unequal access to environmental amenities depending on the demographics of a neighborhood.

Keith Christensen: I started working on playgrounds for kids and could see that just being able to get around the playground doesn’t mean you can actually play. Proximity is not the same as participation. If you expand that from the world of a playground to the adult world of a community, we do the same thing, but we often don’t realize it. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was a shock to see yellow caution tape strung around playgrounds to prevent kids from playing on them because we didn’t know how the virus spread. Now there’s no caution tape, but for a fair number of people, there are still barriers that they can see and other people won’t notice. It’s not always that people with disabilities can’t access a place, it may just be harder and take more effort, more thought, more money, more time. We say, ‘We want you to belong,’ but when you create an environment that charges a high social price for someone to belong, it’s discouraging, like wrapping caution tape around a playground.

What are some of the things we may not notice that keep people out?

KC: If you arrive at a couple of acres of grass and in the middle of it there’s a picnic table under a tree and no paths or connection, it leaves you questioning what the space is for. Is it really for picnics? Did people want a place to sit for a soccer game? You don’t want barriers like steps, and it’s inviting to see water fountains, restrooms, and other amenities from your entry point.

Do Americans use city parks in ways that differ from people in other countries or regions?

KP: The city park was born in the United States, and the landscape aesthetic was borrowed from the English gardens that were mostly for royals and the gentry. The way the park was built was teaching middle-class workers or lower-class people the lifestyle of the bourgeoisie, telling them, ‘You need a sense of belonging here, and you gain that by doing things like strolling or picnicking instead of spending time in the streets, or whatever you do in the dark side of the city.’ Parks in the United States have been largely turfgrass; the picturesque view landscape design. Many countries have higher density cities than the United States so they use parks differently as part of community culture. There’s value in some large, pastoral landscape for mental health or restorative functions, but our version of parks in America is often not well-integrated with neighborhoods. Likewise, we create a sports complex that is very separate from the city, and you can only get there with your own car.

KC: Conflicts can occur when one group might use a resource differently than another. You may wish to go play for recreation, but someone else looks at the park as an extension of their home.

KP: Depending on the culture, you use space for different things. So, for one example, Latinx people may use a park for a barbecue more than other ethnic groups.

KC: Yes, and might have a family gathering, while other people think ‘That’s supposed to happen in your backyard, not at the park.’ It’s just a difference in how you treat public and semi-private spaces. But we enact rules to stop some things from happening that are not part of our experience. We put curfews on parks and don’t install lights because we don’t want anything to occur after dark, when really, why couldn’t you still gather with friends at 9 o’clock? You have to schedule a pavilion 48 hours or more in advance. You can’t use a field except with a scheduled team. Truly meeting people’s needs in a community requires flexibility. We tend to look at the design of public spaces and say, ‘Look, we’re creating this space for these people.’ But we never do the flip side of it, where we recognize that when we say ‘for these people’ we’re also saying ‘Not for these people.’ So you have to pay a lot of attention to that.

How do you determine what that looks like?

KC: When I work with communities on including people with disabilities, I make it clear that initially, it will cost a little more. But they’ll have a better design as a result that won’t look like an afterthought. If a change looks like an afterthought to me, then I’m an afterthought. I feel I don’t belong there. Retrofits have fiscal costs, and in social or community capital they cost more.

KP: It’s understandable why people refuse to change the common practice if they don’t know or haven’t seen a lot of the best practices or the state-of-the-art. So that’s the job of professionals, landscape architects, in particular, to demonstrate examples of changes whenever an opportunity arises.

By Lynnette Harris ‘88

View Keun Park’s TEDx – USU talk “If You Build it, They May Not Come.”