A Shared Mission: Preserving the ISS

Photographer Roland Miller has a folder in his office labeled “crazy ideas.”

His latest project, Interior Space: A Visual Exploration of the International Space Station, never made the list. It was too crazy to imagine possible.

“The space station is really a spacecraft that has been orbiting the Earth for 20 years, which is amazing—even the Star Trek Enterprise was only a five-year mission,” says Miller ’80, MFA ’83 from his home in Ogden. The International Space Station (ISS) is a training ground for human life beyond Earth.

It is a partnership in science between five space agencies where astronauts conduct hundreds of experiments each year. The ISS is also a time capsule orbiting Earth at 17,500 mph. Miller’s book Interior Space serves as a visual record of human curiosity and the best technology we had when we began flinging habitable parts into space. Spoiler: It doesn’t resemble the minimalistic environment depicted by Hollywood.

“There are just cables and computers sticking everywhere. It’s chaos,” Miller says. “It’s just a crazy rat’s nest of equipment. I think it’s important for people to see that. This is where we are at. Hopefully, what I am doing preserves and displays some of those things that are not normally shown.”

Longitudinal View, from ISS Forward to ISS Aft

US Laboratory – Destiny. International Space Station – ISS.

Low Earth Orbit, Space

Nadir View of Pressurized Mating Adapter

Node 1 – Unity. International Space Station – ISS.

Low Earth Orbit, Space

Astronauts aboard the ISS work and live together for months at a time in a sealed 13,696 cubic foot facility. For most humans, the most we will see of the ISS is during the brief intervals it is visible to the human eye as it traverses lower Earth orbit. A tiny fraction step (float?) inside. Miller and Italian astronaut Paolo Nespoli collaborated on a photography project to document the ISS for future generation—because all missions come to an end.

“We are not going to be able to save it,” Miller says. “It is too big to bring the pieces down. Someday, probably in the next few years, it is going to have to be de-orbited.”

Photography is a way to preserve it. Miller’s storytelling voice emerged at Utah State University. He came to major in forestry but pivoted to photography as a freshman.

“I had no idea how deep and how broad and how varied photography was,” Miller admits. “I liked taking landscape pictures. Utah State really helped me understand and lay a foundation for everything I have done since then.”

Professors Ralph T. Clark and Craig Law helped Miller crystallize his approach. He learned to balance the technical with the aesthetic and the strengths of fine art with commercial photography. He learned the human aspect of photography and its power to inform and even change minds, Miller says. He began photographing space relics while teaching at Brevard Community College in Cocoa, Florida, near Cape Canaveral. While out to dinner he heard “a tremendous rumble” and ran out to watch an unannounced launch—the first of many he would witness.

It rekindled the awe Miller experienced watching the moon landing on television as a kid.

“At that point in time, to be an astronaut you had to be a pilot, which meant you had to have 20/20 vision. I got glasses in the third grade. I knew that there was no way I was ever going to go into space.”

– Roland Miller

“At that point in time, to be an astronaut you had to be a pilot, which meant you had to have 20/20 vision,” Miller says. “I got glasses in the third grade. I knew that there was no way I was ever going to go into space. Now, pretty much all the astronauts on the ISS end up wearing glasses because the lack of gravity changes the shape of your eye. The irony to me is poetic on some level.”

Corrected vision or not, Miller’s eye for composition and subject matter has kept him busy photographing decommissioned launch sites littered across the country for the last three decades. Each location is a step along humankind’s path to the cosmos. Miller’s abstract style in his book Abandoned in Place: Preserving America’s Space History, named for the words stenciled on the retired facilities, hints at a darker history of the space program.

“The early rockets they launched people on were missiles originally designed to launch warheads, mainly at Russia,” Miller says. After the Cold War, space exploration shifted in scope. “We took these things that were meant for very destructive use and turned them into a much more peaceful use.”

The ISS represents that hope. Its mission is shared across space agencies, including Russia. Miller’s project with Nespoli embraces that collaborative spirit. But it was an unlikely affair. The concept was first suggested by astronaut Cady Coleman who challenged Miller to find a way to get his vision inside the ISS. A giant hurdle remained: gaining permission.

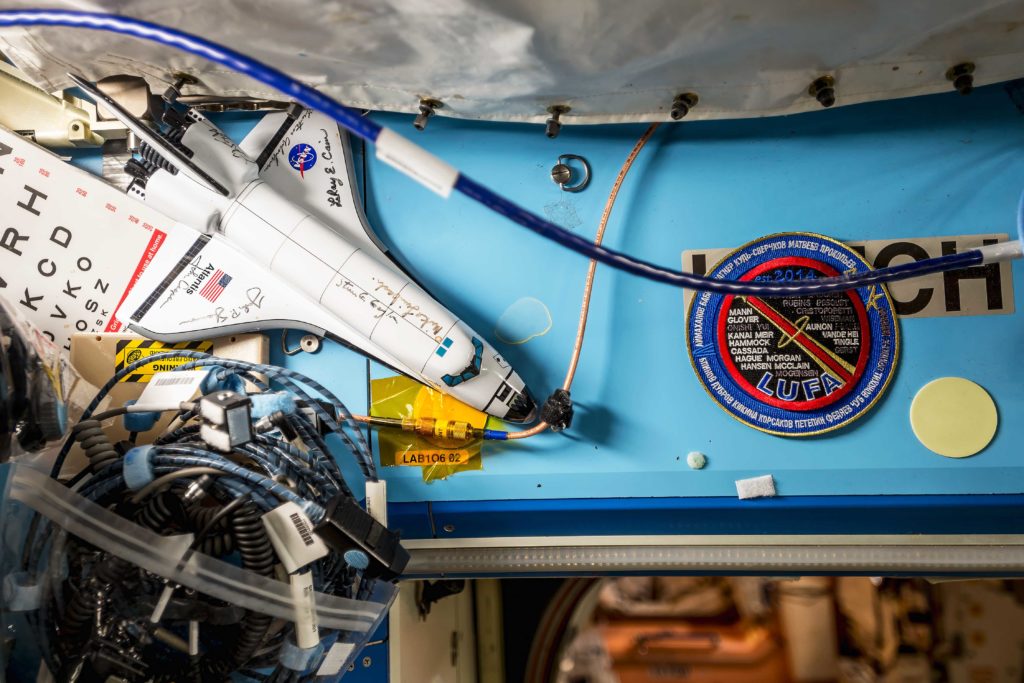

Signed Space Shuttle Atlantis Model, Eye Chart,

Cabling, and Patch

US Laboratory – Destiny. International Space Station – ISS.

Low Earth Orbit, Space

Nadir View of Extravehicular Mobility Units and

Extravehicular Activity Hardware in Equipment Lock

Quest Joint Airlock. International Space Station – ISS.

Low Earth Orbit, Space

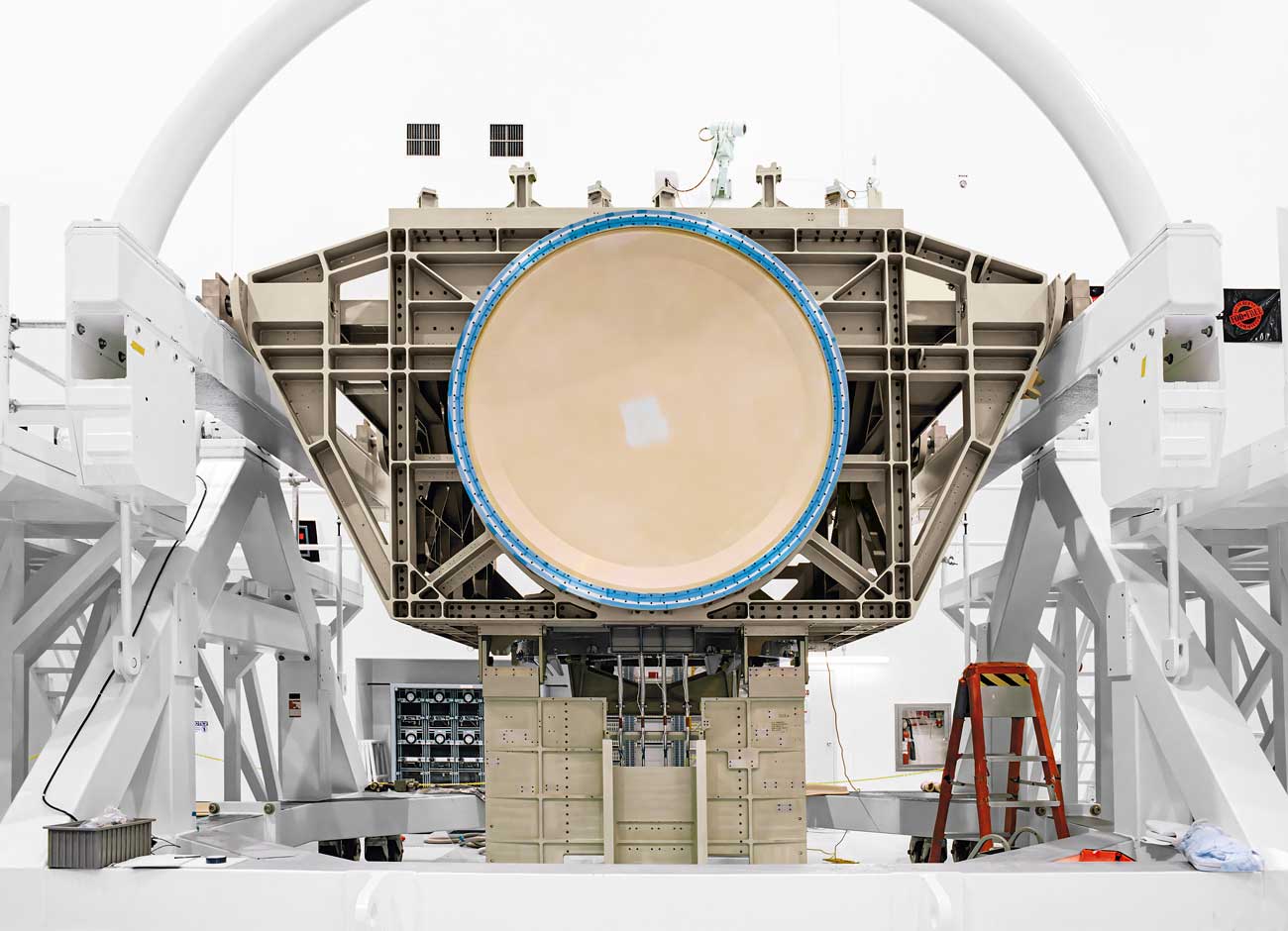

THE CUPOLA is one of the most photographed parts

of the ISS because of its front seat view of Earth.

Paolo Nespoli still managed to capture this shot that

stunned even Roland Miller for its dreamy composition.

“Astronaut time is the most valuable resource on the space station,” he says. “If you make a mistake while doing an experiment, it might never get done.”

Miller needed to find someone willing to share in the artistic vision and take on the project in their personal time. Coleman suggested Nespoli, an astronaut she had worked with who also shared a passion for photography. He called Miller for details.

“From the get-go, Paolo talked about the importance of including the humanities in space exploration,” Miller says. “He thought we should be sending artists and writers, dancers, and theologians into space to translate that experience for the rest of humanity.”

Nespoli suggested the two photographers email images back and forth rather than attempt a real-time effort unlikely to be approved. Miller visited the full-scale mockup of the ISS at the Johnson Space Center to understand what, where, and how Nespoli should shoot and leaned heavily on the ISS Google Street View to direct the composition. Nespoli shot over 500,000 photos, most time lapsed, for the project.

“Looking through this book, I finally understand what “space archaeology” means: it’s a documentation of what we, the human species, have been capable of achieving in space not only from a technological point of view, but also from a human point of view,” Nespoli writes in Interior Space. “Just look at the complexity and intricacy of this high tech marvel along with all the little signs we have dispersed around it to make it cozy, livable, and civilized. It’s a perfect documentation of what we are: thoughtful beings, humans.”