Why Are We So Divided?

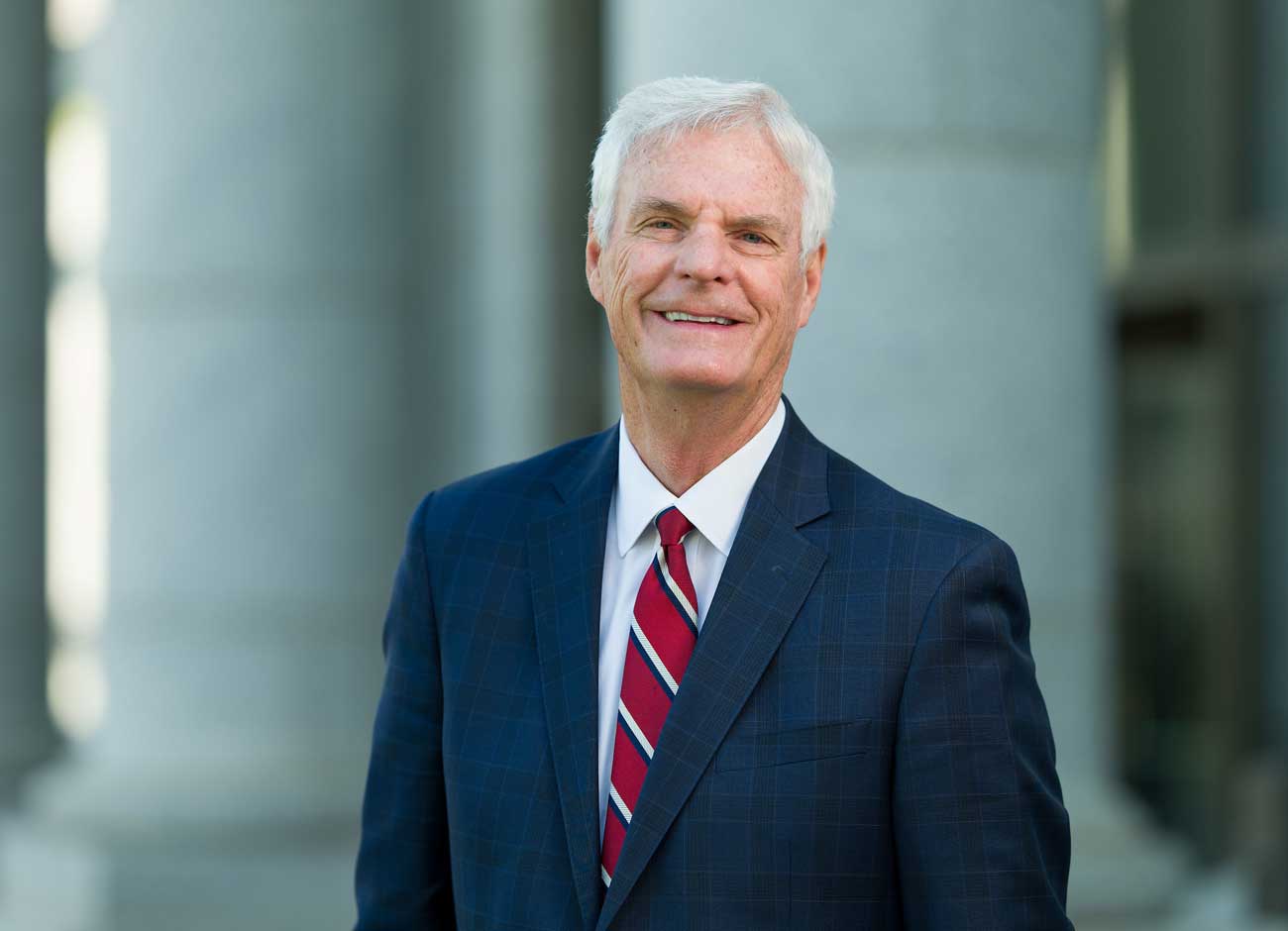

Brent Hill ’73 of the National Institute for Civil Discourse weighs in.

While serving as senate president pro tempore of the Idaho Senate, Brent Hill BS ’73 was called upon to make a trip to Washington, D.C. for a meeting at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. Located directly west of the White House, the building houses the offices of the Vice President of the United States, and Hill was a little taken aback when former VP Mike Pence suddenly stuck his head into the conference room.

“It was getting late in the day, but he ended up visiting with us for about 20 minutes and let us ask questions,” Hill says.

Pence’s surprise visit showed off his sense of humor and the “human side of one of our leaders,” he says. But Hill, a Republican from Rexburg, took note of a serious moment during the conversation in his journal.

“Vice President Pence said, ‘Folks, we’ve got some challenges in our country. And I hope that if you are inclined to bend your knees that you will pray for our country,’” Hill recalls. “And he quickly said, ‘I’m not asking you to pray for any particular person or any particular party. Just pray for the success of our country.’

“And I just thought, That’s what we’ve got to do,” Hill continues. “Regardless of whether the Republicans are in power or the Democrats are in power, we need to pray for the success of our country. And as we do so, we’re committing ourselves to the success of our country and to the success of our fellow citizens.”

After spending 19 years in the Idaho Senate, Hill decided it was time to step away from public service at the end of 2020, but not from trying to aid in the success of his country. Starting last July, Hill began his new role as the director of the Next Generation program at the National Institute for Civil Discourse (NICD).

Founded 10 years ago with the aid of honorary chairs George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton, the NICD was created as a “nonpartisan center for debate, research, education and policy generation regarding civility in public discourse,” according to its website. And Hill’s role as program director is to make presentations and hold workshops for state legislatures around the country to help improve civility among lawmakers.

A retired accountant, Hill and his wife, Julie, recently relocated from Rexburg to Layton to be closer to children and grandchildren. But in between attending ballgames and concerts, much of Hill’s time is dedicated to sharing the concept that “civility is more an attitude than it is an action, and if you have the attitude, the actions are going to follow most of the time.”

Hill, whose 10-year tenure as senate president pro tempore was the longest in the history of the state of Idaho, was asked for his thoughts about why things seem so uncivil in United States politics today. The conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Jeff Hunter: What prompted you to initially get involved in politics?

Brent Hill: I have always been fascinated by politics. I love American history, and I love studying the Constitution and our way of doing government. It’s slow and cumbersome and frustrating—just the way it’s supposed to be. And I had toyed with the idea of getting into politics, but I was a little shy for it. I knew I probably wouldn’t have the disposition for it. In fact, even after I got elected, my mother said, ‘You of all our kids … you were the sensitive one.’

But being a CPA, I ended up being the treasurer for a number of different local legislators, and one of the people I was a treasurer for was Bob Lee, our senator from our district. He got cancer and resigned in the middle of his term and we went through an interview process with the district central committee, and they made a recommendation of three names to the governor for a replacement appointment. And I was fortunate to be at the top of the list. Former Idaho Governor Dirk Kempthorne appointed me on Christmas Eve 2001. I served that year and loved it.

JH: How did you first become involved with the National Institute for Civil Discourse?

BH: After I announced that I was not running for re-election they contacted me. They’re located in Washington, D.C., but actually sponsored by the University of Arizona. It got started in 2011, back when Congresswoman Gabby Giffords got shot. She was already working with the University of Arizona to set up some kind of program to help promote civil discourse, particularly in politics.

JH: You were already familiar with the NICD, I presume?

BH: Idaho was actually the first legislature where they had the full legislature there for their workshop. “Building Bridges through Civil Discourse” is what we call it. House Speaker Scott Bedke and I worked closely together when I was President Pro Tempore, and we’re the ones who kind of stuck our necks out. We weren’t quite sure how well it would be received. But out of 105 legislators, 103 of them showed up. And I was very impressed with the program and felt like it had done some good in Idaho.

JH: Has the Utah State Legislature ever participated in a NICD workshop?

BH: I don’t think they have; Utah’s one of the few Western states that have not. I plan to talk to Utah Senate President Stuart Adams about it. I’ve just been waiting until we could travel more and do a real, live session. Our sessions usually last four and a half hours, but with these virtual sessions we’ve cut back to two and a half hours. And obviously, they’re not quite as effective. And I want to make a good impression on my now home state. We’ve done 29 workshops in 18 states, most of them in the West, Midwest, and northern states. Our weakest area so far is in the southern states, so we need to reach out to them more.

JH: Have you found the response different, depending on the political climate in a particular state and whether it leans red or blue?

BH: Yes. Quite frankly, I think the democratic states are more receptive to trying to generate more civility in the political discourse. I’m talking about in general, certainly not as individuals. We’ve already done three workshops in Kansas, which is a very, very red state, but they have put together a civility caucus as a result of the meetings that we’ve had with them.

But there are individuals in both parties, and in and all kinds of states that are interested in it. But I think that as I look at the states where we have actually done workshops, there are probably more blue states than red states.

JH: Why do you think our country is so divided right now, seemingly more so than any of us have seen in our lifetimes?

BH: That’s a real good question. It’s a question we try to talk about at our workshops, and there are some common themes that come through from lawmakers. A lot of factors that go into it, for instance, the internet and political rhetoric by some of our political leaders and in political campaigns. Overall, campaigns are meaner than they used to be.

But I think a lot of these things feed into the fact that is so much easier now to create our own echo chambers. And the pollsters will verify this, as well, that, more and more, our society is dividing itself by where they can find the most political compatriots. They don’t listen to news media that has a different point of view; they listen to their news media that says the same thing that they believe. The same thing with blogs and other sources on the internet. They turn into those who reinforce the things that they believe.

Even at work, people kind of segregate themselves into work that kind of think the way that they do. As a consequence, when you create your own echo chamber, you start to believe that everybody thinks the way you do because everyone around you thinks the way that you do.

JH: Thanks to social media and new media outlets, it certainly seems like it’s easier to be selectively siloed.

BH: And if you come across someone that thinks differently, or has a different opinion, well, it must be because they’re uninformed or they’re uncaring. Or because they’re just plain dumb. And so, we begin to villainize them, to alienate them. And then we go back again to our sources, and sure enough, whatever we’re listening to on the internet or whatever our news sources are, they’re verifying that I’m right, which means that they’re wrong. So, it’s not a matter now that we’re both somewhat right and we both might be a little bit wrong, too. It’s the good guys and the bad guys. And any movie that you watch that has good guys and bad guys, you know there is no tolerance for the bad guys.

JH: In your 19 years in the Idaho State Legislature, did you see in an increase in division, even in a state where the GOP is the dominating party?

BH: Oh yeah. But it’s OK to have differences of opinion. It’s all a manner of how you handle those, how you work together on them. We should not shy away from people that disagree with us. We need to be making friends and communicating with those people who disagree with us. We can learn from one another. But I saw less and less of that.

Now, when you get into a very heavily partisan state—whether it’s blue or red—you’ll find that a lot of the infighting goes on within the party itself because the other part becomes less relevant. So, you don’t direct your contempt towards the other party. You direct it towards people within your own party which causes problems, and it certainly makes those primary elections even more contentious.

JH: The events January 6th at the U.S. Capitol showed an alarming lack of civility in this country.

BH: In my experience there are a lot of good people at the federal level who walk the walk. Who really are concerned about civil discourse in politics, about having mutual respect for their colleagues or working across party lines. Unfortunately, sometimes they get defeated in elections because of it. Compromise, to some people, has become a dirty word. Although, we wouldn’t have our present constitution if it weren’t for the principle of compromise.

I have a great deal of respect for a lot of people at all levels of government who are willing to put their political careers on the line in order to stand up for the principles which they believe are true. I’m talking about principles of decency and respect.

JH: It sounds like you are still optimistic that things can get better.

BH: I guess I don’t know that I’m an optimist, but I know I’m not a pessimist. I really believe in our country, and I really believe in the people of our country. And a few bad apples don’t spoil the whole barrel of us.

There’s a lot of good people out there, and I have to keep reminding myself as I think we all do as we see the discontent in our country. There are far more good people in this nation than there are bad. And we saw that coming out during this pandemic, while we saw some people at their worst.

And maybe politics was at its worst during this pandemic, or at least the worst that we’ve seen. People are frustrated, they’re tired, and they’re trying to jockey for power if you’re in politics. And yet, we’ve seen some of the kindest acts of charity with people the way they’ve helped their neighbors and have helped strangers.

We saw that over and over again, particularly from healthcare workers. We really saw people at their best, and I really believe that there’s a lot more of those than there are the others.