A Fish Tale

Mike Simpson ‘77 was having lunch with his mother and two of his uncles in November 2021 when he felt it necessary to divulge his ambitious plan.

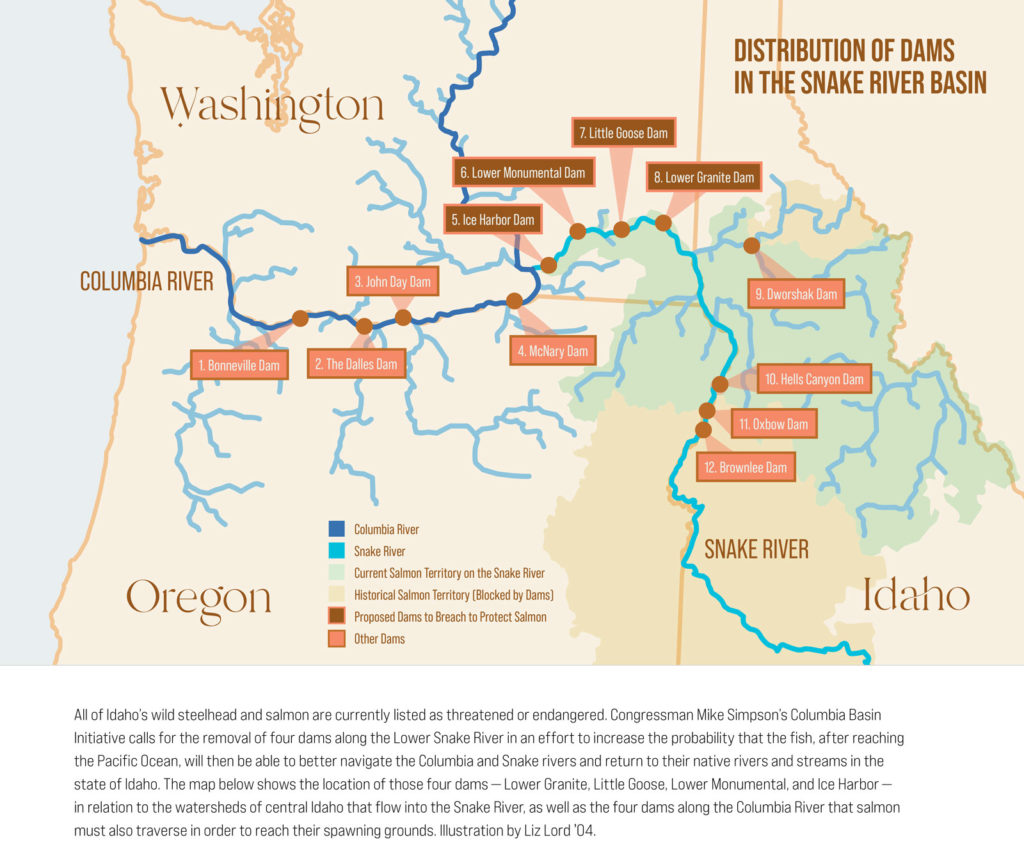

A U.S. congressman from the state of Idaho since 1999, Simpson was about to unveil the Columbia Basin Initiative (CBI), a proposal that calls for breaching four dams to help preserve the Gem State’s wild salmon and steelhead runs.

“I told them, ‘Well, all hell’s going to hit the fan about February,’ and they said, ‘Why?’” Simpson recalls. “I said, ‘I’m going to put out a proposal to save Idaho’s salmon runs that are going to extinct in the next 10 to 20 years if we don’t do something about. And it’s going to involve the removal of dams on the Lower Snake River.’”

Simpson says his uncle Ferrol Simpson, a retired engineer, looked at him and declared, “That’s the stupidest idea I’ve ever heard of. … We need the power.”

Simpson explained that since the construction of the Lower Granite, Little Goose, Lower Monumental, and Ice Harbor dams in the 1960s and ‘70s, a variety of new ways to produce electrical power have been introduced, including wind, solar, and smaller, more efficient nuclear reactors. But Simpsons says he dropped the topic after that, but soon his mother and uncles started recalling horseback trips into the rugged mountains of central Idaho. During one of those family adventures, the Simpson encountered a stream full of what they originally believed to be black rocks. But the “rocks” turned out to be hundreds of spawning salmon.

Simpson acknowledged that those sounded like “great memories,” and then asked his Uncle Ferrol, “Do you want your great-grandchildren to be able to create those same kinds of memories?”

“He looked at me with a tear in his eye and said, ‘You know, I would.’ And he’s become one of the best supporters of this because he realized that we’re not doing this for us,” Simpson notes. “I’ll probably be dead before these fish go extinct. We’re doing it for future generations so that they can also have the same opportunities to enjoy the great Idaho outdoors that we had.”

Needless to say, the idea of breaching four hydroelectric dams to save Idaho’s salmon runs is a controversial and expensive one. And one that’s been proposed by various environmental groups in recent decades with no success. But Simpson is passionate about the Columbia Basin Initiative because, “I can see the train coming down the tracks. And that train is these fish going further and further extinct.”

“I’m trying to look down the road some,” Simpson adds, “and if you’re in this job and you’re not trying to solve a problem, then you have to ask, ‘Why the hell are you here?’”

Simpson, who grew up in a family of Aggies says, “I thought you went to Logan after you finished high school. I just assumed that was the next step.” He attended USU with his wife, Kathy ‘72 after graduating from Blackfoot High School in 1968. Although he eventually followed his father into a career in dentistry, he toyed with the idea of pursuing a degree in political science. It wasn’t until he decided to seek a spot on the Blackfoot City Council in 1980 that he got into politics, and Simpson served seven terms in the Idaho State Legislature, including Speaker of the House from 1992 to ’98.

When longtime U.S. Congressman Mike Crapo opted to run for the Senate in 1998, Simpson successfully ran for his seat, and he will be seeking his 13th term in Congress this November.

The veteran Republican, who originally unveiled the details of the Columbia Basin Initiative in February 2021, strongly believes that the Lower Snake River dams will be taken out sometime in the future regardless due to a court order to preserve Idaho’s wild salmon runs via the Endangered Species Act. Simpson says he feels it would be far better to orchestrate the breaching of the dams in a timely manner that would better accommodate large changes in transportation, agriculture, recreation, and electrical power.

“It’s complicated and potentially very expensive,” acknowledges Simpson, who calls for $33.5 billion of federal funds in the CBI.

Adding to the obvious challenge of replacing water storage and hydropower is that the locks attached to the dams allow for grain to be transported downriver from Lewiston — the furthest inland port in the country — to the Columbia River. The CBI calls for the use of electric trucks and trains to help transport the grain, while Simpson notes that 487,000-acre feet of water from southern Idaho is used every year to help flush salmon over the dams.

“And guess what? We’ve been doing that for a number of years, and it hasn’t done anything. The fish are still going extinct,” Simpson says. “And we end up losing all of that water in southern Idaho, and we’ve already got an aquifer that’s being depleted.”

The dams, which are all located in Washington, are a huge hinderance in the salmon’s 900-mile journey to return to the rivers and streams of Idaho after going down the Snake and Columbia rivers to the Pacific Ocean. The salmon already have to navigate four dams on the Columbia via fish ladders while heading east, and their rate of survival drops dramatically compared to the salmon who may swim north or south into their native drainages in Oregon and Washington rather than continuing on and encountering the dams on the Lower Snake River.

“All of those fish have had to deal with the same things in terms of predators and ocean conditions and other conditions, the only difference is the number of dams they’ve had to go over,” Simpson points out. “The fish passage on the dams is tremendous, between 90 and 95%. That’s good fish passage. But that’s between 90 and 95% at each dam, so you if you go over eight dams, there’s just a point where that’s too much.”

Sarah Null, an associate professor of watershed sciences at USU’s Quinney College of Natural Resources, compares the monumental effort by salmon to return to the river of stream of their birth to running of a “gauntlet.”

“It’s not easy. A lot of people think, we’ll just build a fish ladder, and the fish will be fine,” Null says. “But we know that there can be problems like predation, or that sometimes fish ladders are dependent on specific flows or temperatures. And that too often leads to the trap and haul, so we resort to putting fish in trucks and hauling them around these barriers. And we lose a lot when that happens.”

Null says in the long run it might also be more feasible to breach the dams “rather than put tons of money into programs that, after decades, we don’t have a lot to show for.”

“The Snake and Columbia are both basins that taxpayers have been paying a lot of money for restoration,” Null continues. “So, from an economic standpoint, is there a better way to do this? And as far as dams being the only solution to water problems, I think it’s important that we think more creatively or innovatively looking towards the future. Sometimes dams that were built 50 or 100 years ago no longer make sense in the 21st century.”

When the Biden Administration proposed the $1 trillion infrastructure bill in early 2021, Simpson attempted to get the $33.5 billion for the Columbia Basin Initiative included in the package. The CBI was left out, but Simpson says it certainly doesn’t mean the end of the plan which needs to be drafted into legislation. The 72-year-old, who now lives in Idaho Falls, continues to work with other politicians, particularly those in neighboring Washington and Oregon, to build additional support for the “complicated” proposal which calls for the removal of two dams in 2030 and the final two in ’31.

“There’s still a lot of work that needs to be done,” Simpson admits. “But I will tell you, in the future, I firmly believe those dams will come out. It is the best chance we’ve got. In fact, I think it’s the only chance we’ve got.

“When you look at the facts, you’re going to have to either take the dams out or you’re going to sacrifice salmon. … It’s one of the two.”

By Jeff Hunter ’96

Lead image by Dan Hershman