The Unofficial List Keeper

In 1982, when Utah State University reached out to me to apply for a faculty position directing the writing center in the English department, my answer was, “I’m not interested,” but Bill Smith, the director of the composition program, was convincing.

“Just send us your CV,” he said. Later, when he called to invite me to campus, I continued to drag my feet, “I don’t want to waste your money.” Nearly 40 years later, I’m glad I was wrong. What happened?

I landed in Cache Valley at a time when commercial flights still made the hop over the mountains from Salt Lake City. The stunningly beautiful environment, coupled with a warm welcome, won me over almost immediately. When the job was offered before I returned to the Midwest, I said yes. Although I’ve had stretches away on sabbatical research leaves, my commitment to USU started all those years ago continues.

A benchmark moment in my initial interview occurred when the department head said, “We need strong role models for our women students.” Admittedly, I was taken aback. That aspect of a faculty role had not occurred to me. Throughout the decades, though, I have felt the responsibility of carrying the banner of being a professional woman, and I’ve been aided along the way by various groups of women on campus and in the larger community. Others could tell similar stories; this is mine.

In the decade prior to my arrival, USU was exploring how to improve opportunities for women students, staff, and faculty. In 1972, the year I graduated high school in Missouri, a committee to advance the status of women was formed. They helped write an Affirmative Action Plan and hired the first woman in the Counseling Center, Marilynne Glatfelter. A special leave policy enabled women to complete Ph.Ds. The Women’s Center for Lifelong Learning was dedicated in 1974 by First Lady Betty Ford, on campus for her son’s graduation. Did she know that the space was formerly the women’s restroom on the third floor of the Taggart Student Center?

Cecelia Foxley, who became Commissioner of Higher Education for the state in 1980, was appointed assistant vice president of student services, a rare woman in central administration. She was also one of five women with the rank of professor. The last woman in my own department to hold the rank was Veneta Nielsen, a poet and advocate for women, who retired against her will in 1974, prior to the removal of a mandatory retirement age.

I could not have been luckier to find such diverse and interesting communities of women; they are the primary reason why I didn’t wander too far from Cache Valley.

Soon after arriving in 1982, I was invited to a late afternoon gathering of faculty women in the backyard of the President’s Home, and I was rather shocked to find that I was in a group of “faculty wives” rather than faculty members. More happily, I attended an update on the Status of Women Committee by President Stanford Cazier. The Women and Gender Research Institute was formed soon after.

The paucity of women leaders on campus was notable among students, too. The first woman student body president, Michelle Henrie, was not elected until 1986. An influential role model for me was Karen Morse, department head for chemistry and biochemistry, then dean of science, and eventually provost. Karen’s visibility in these leadership roles was significant for those of us advancing in our own careers.

One of the most important women’s groups to me was “Fridays,” academic women who were actively involved in improving the status of women on campus. As Alison Comish Thorne noted in her memoir, Leave the Dishes in the Sink, the women in Fridays “gave each other a leg up in our academic careers, shared joys and accomplishments, and stood by each other in difficult times.” Another gathering of women in professions across the valley, BC—an acronym for Before Clio that resulted when some Clio members found that cocktail hour was perhaps more interesting than the actual club—also adopted me. And, yet another group of community women told me frankly, “If you want to hang around with us, then you’ll have to learn to ski and play bridge.” I could not have been luckier to find such diverse and interesting communities of women; they are the primary reason why I didn’t wander too far from Cache Valley.

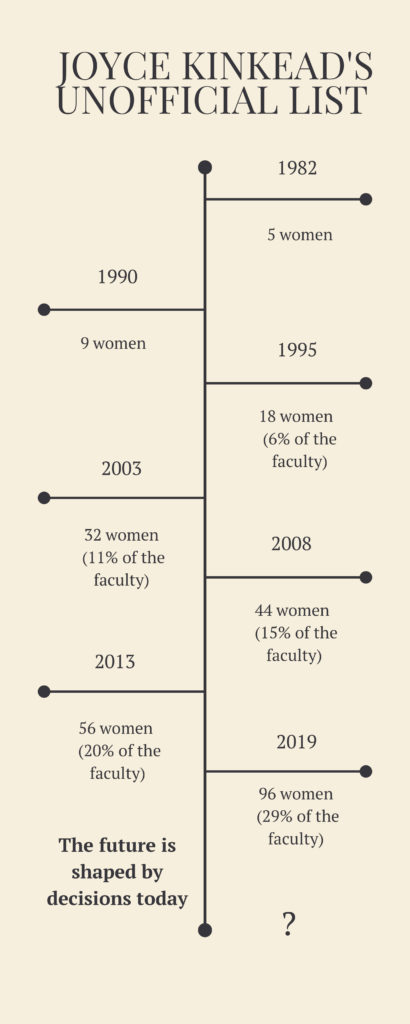

When I earned promotion to professor in 1990, I became an unofficial keeper of the list of women of that rank. By this time, we could count the number of women “fulls” on two hands: nine individuals. Over the years, the figure grew. In 1998, one addition surprised me, as I thought I knew all women faculty on campus: Noelle E. Cockett. “Who is this?” I asked the other women. We were certainly going to find out. By 2000, the count was 32, and the Utah System of Higher Education released its “Annual Report on Women and Minorities in Faculty and Administrative Positions,” prepared for Commissioner Foxley. A goal was for the faculty and administrators to reflect the increasing diversity of the student body.

Why is the rank of professor so crucial to women’s opportunities in academe? Individuals who are successful over the probationary tenure and promotion from assistant professor and on to professor, are more likely to be tapped for leadership positions. And that was the case for me.

My interest in administration was whetted by directing USU’s Writing Center and shortly thereafter, the composition program. Problem solving, an important part of any organization, was stimulating. I became the first woman to serve in a leadership role in the College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences and the first woman to have an administrative position in the Office of Research as associate vice president overseeing undergraduate research. I later became vice provost, charged with overseeing undergraduate education.

Seeing women in leadership roles is extraordinarily important to girls and women. From my own upbringing on a farm with a 4H background, most women worked mainly in traditional jobs as teachers and librarians, who opened the world to me through books.

Throughout these roles, I felt keenly the privilege and responsibility of being a visible woman in leadership. After all, when I arrived on campus, many departments included no women whatsoever on the faculty. It’s been a slow advance. While every college but one has had a woman serve as dean, and, finally, a woman serves as our 16th president, only 28% of the faculty at the professor level are women.

However, USU has taken proactive steps to increase hiring, retaining, and promoting women faculty, and also faculty of color. A five-year National Science Foundation ADVANCE Institutional Transformation Award increased faculty hires in STEM areas dramatically. Diverse reasons contributed to the lack of women. Early on, women were not as likely to seek careers in STEM fields, sometimes attributed to gender and cultural norms. Implicit bias may exist in hiring, tenure, and promotion decisions. Then there is the situation of women who must juggle multiple roles as professional, wife, and mother. USU researchers such as Christy Glass and Alison Cook, and Gary Kiger before them, documented unbalanced workloads in the home.

Seeing women in leadership roles is extraordinarily important to girls and women. From my own upbringing on a farm with a 4H background, most women worked mainly in traditional jobs as teachers and librarians, who opened the world to me through books. As first-generation college students, my sister and I did not bring to campus the social, cultural, or political capital that would have made the transition from farm kids to coeds easier. When I oversaw undergraduate studies and research, a priority was to introduce our first-year students to opportunities from the first days of their campus experience.

Here we are in 2020, celebrating the Year of the Woman, an initiative by President Cockett, co-chaired by Sydney Peterson and me, that recognizes important voting rights: the ratification of 19th Amendment in 1920, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and, of course, Utah’s role of having the first woman to vote in 1870. We have uncovered important histories of women of USU.

Scholar Carolyn Heilbrun writes “women in the past have a dreadful tendency to disappear in a cloud of anonymity and silence, . . . and one does feel impelled to recover their voices and stories.” My story has been a remarkable one. Growing up I never foresaw my good fortune in landing at a land-grant research university that offers opportunity, professional and personal growth, and the important support of an Aggie family. Whenever I consider the slowness of women’s advancement or enduring misogyny, I reflect on the long line of women who persisted in fighting for their right to vote to be recognized.