Care for a Saltless Saltine?

LYNN THOMAS WALKS IN THE SPITTING RAIN TO THE DARYL CHASE FINE ARTS BUILDING.

His keys jingle as he describes growing up in Hyrum during the height of the Cold War — a time when neighbors erected fallout shelters in the mountains and classmates performed duck and cover drills in school. Mid-sentence Thomas stops to point out the telltale yellow fallout sign drilled into the brickwork of the arts building. “A relic of another time.”

Thomas, ‘73, director of production services for Utah State University’s Caine College of Arts, heads down a flight of cement stairs and unlocks the basement door. Racks of blue marching band costumes line the path to a chain-link fence. Thomas tracks further into the bowels of the basement to a room marked 001A. Thomas twists the knob and the first thing one notices is the darkness. Until about four years ago it was full of old survival kits, he says. “They kind of thought of everything.”

The packs were cylindrical, about the size of an office garbage can, and stacked to the ceiling, Thomas says. The interior was packed with military rations, plastic-wrapped hard candies — “the kind your grandma gave you”— and heaters to warm the food. The bucket itself was a personal latrine. Today, the shelves of the former fallout shelter store electric cords, microphones, cables, lighting — items rendered largely useless during a nuclear attack.

“We probably should have saved one [kit] for old time’s sake,” Thomas says.

The Chase Fine Arts building opened in 1967. Architect Burtch Beall Jr. designed it in the brutalist vein popular during that era, Thomas says. “That tells you something about the time.”

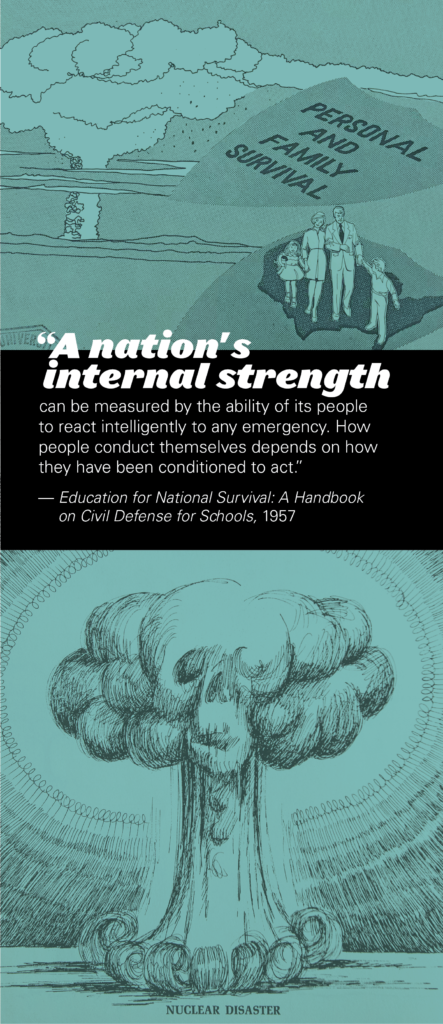

The first hydrogen bomb was detonated on the island of Elugelab in the Marshall Islands in 1952. The only thing that remained of Elugelab was a crater one mile wide and about 170 feet deep. Over the next decade the United States and Soviet Union amassed war chests filled with thousands of nuclear warheads. It seemed humankind might just blow up the world.

One year into the civil defense program, nearly 104 million shelter spaces were identified nationwide. This is where the good news ends.

On July 20, 1961, three months after the failed Bay of Pigs operation in Cuba, President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10952; it tasked the Secretary of Defense with developing a robust civil defense program, the core of which centered around a national system of public and private fallout shelters. The now defunct Office of Civil Defense aimed to secure 240 million shelter spaces by 1968. One year into the civil defense program, nearly 104 million shelter spaces were identified nationwide. This is where the good news ends.

“They had way more shelters than they had stocked,” government information librarian Jen Kirk says as she carries an armful of pamphlets to a table in USU Special Collections. Less than 10 percent of the shelters were stocked, she says.

Kirk opens one titled Highlights of the US Civil Defense Program. A map of the United States depicts where fallout might occur after a range of random attacks on a spring day. Only Oregon is spared. Fallout is the dirt and debris that gets sucked skyward after a nuclear blast. It rises with the expanding mushroom cloud and gets covered with radioactive particles as the gases cool and condense. Eventually, the fallout drifts back to the ground and spreads with the wind, blanketing the earth with radioactive material.

This is where shelters come in to play. If the initial explosion and heat didn’t kill you, the fallout might. Persons fortunate to find themselves in one of the few stocked fallout shelters would have a meager ration of food — 10,000 calories per shelter space — and access to basic medical supplies including petroleum jelly, penicillin tablets, surgical soap, bandages, thermometer, and sanitary pads.

In 2019, it’s unclear how many fallout shelters existed at Utah State University during the Cold War. No such records exist and remnants of the shelters have either been relegated to storage, raised during new construction projects, or forgotten entirely. However, the documents that remain in USU archives indicate that USU Extension was heavily involved in doomsday planning.

The U.S. Department of Defense awarded USU Extension a $40,000 grant to teach civil defense as parts of its programming. Beginning in 1963, USU Extension taught courses in radiological monitoring and shelter management around the state. USU President Daryl Chase sent personal invitations to city and county officials to boost participation. Each shelter management course was conducted in a mock fallout shelter and lasted, at minimum, 20 hours.

Shelter managers were responsible for reporting information such as the number and condition of shelterees, supply quantities, and radiological monitoring levels to the nearest Emergency Operating Center. Shelterees were provided three meals a day consisting of eight government issued biscuits at breakfast and lunch, 10 more biscuits at dinner, and washed down with 6 ounces of water.

“Class members brought their family members and friends to the shelter,” reads the first annual report of USU’s Extension Civil Defense Program. “This increased the value of the exercise considerably.”

Kirk slides an accordion folder across the table containing files of Extension materials donated to the library by community members. In the same folder as circulars on vegetable varieties recommended for growing in Utah, home laundering, and producing hogs for profit, is a green-gray pamphlet called “Fallout protection when you’re not prepared,” which describes ways for citizens to create makeshift shelters out of existing spaces like root cellars and basements.

“It was a drill, but for me it was real. I was convinced when they opened the door that Cache Valley was going to be leveled.”

A second folder of similarly benign subject matter like “Christmas Tree Growing for Profit,” “Making and Judging Needlework,” “Dressing your Windows,” and a babysitter’s guide to childcare, contains a fact sheet designed to be tacked by the telephone in case of nuclear disaster. It reads “Don’t panic. You can survive if you know what to do.” The threat of nuclear war was very much alive in the public sphere.

Christine Lord’s father, Theophil Erni, an employee of USU facilities, took advantage of educational opportunities and participated in some of the university’s workplace preparedness programming — “like Master Gardener, but for civil defense,” says Lord ’74.

When building the family’s new home, Erni built a bomb shelter in the basement. He numbered the cinder blocks and installed a lead screen across the window. One evening he took Christine, then about 11, and her younger brother Martin to the Ray L. & Eloise H. Lillywhite building for a fallout drill. She recalls walking down a set of stairs into a shelter and seeing so many people it was difficult walking between the rows and rows of cots. We ate “these horrible crackers, like Saltines without the salt,” she says.

In the background, a sound reel of bombs blasting played back-to-back inside.

“I thought for sure we were being bombed,” Lord says. “It was a drill, but for me it was real. I was convinced when they opened the door that Cache Valley was going to be leveled.”

She spent the night just trying to fall asleep. In the morning, when Lord climbed the stairs and peered outside she was surprised to hear birds chirping and see the sun shining overhead. “I was just relieved that the earth was still here.”

USU Editor September 5, 2019

Hi Lee,

Thank you for writing about your family’s experience. I can’t imagine what it felt like being a kid and entering one of those shelters and trying to grapple with the what and why of it all. Or what it was like for parents having to explain nuclear war to children and what it would mean. I have two little boys and wonder how they would handle being in a shelter and the questions they would ask. Perhaps this story will give others pause to consider the weight of it all, too. And how serious the threat really was.

Best to you,

Kristen

Lee Sjoblom September 4, 2019

Kristen,

I grew up in the Salt Lake Valley during the 1960’s. My dad was a Captain in the U.S. Air Force Reserve at Fort Douglas as Military Police Officer. During one of his weekend warrior exercises our family volunteered to stay in a Civil Defense Bomb Shelter at Murray High School in Salt Lake City, with several other families, for three days and two nights. We lived in the shelter just like it was a nuclear bomb being dropped and the fallout that followed.

Your article brought back a lot of memories about that experience. I don’t think a lot of people realize how serious the nuclear threat was. Thanks

Lee Sjoblom graduated USU 1977 in Forest Recreation. My dad: Paul L. Sjoblom graduated USU in 1948 in Range Management.