Women’s Movement Redefined

THE LETTER READS LIKE A SMIRK—DASHED OFF ON TWO PAGES OF LETTERHEAD AND SCRATCHED IN THICK BLACK CURSIVE.

“I was taken aback to think that a university would fund such a study,” a Colorado physician’s assistant wrote concerning LaJean Lawson’s MS ’85 research on the sports bra. “I meant that you put so much time and effort into what honestly reads ridiculously. You could have spent the grant money better by strapping the gear yourself and jogging a few laps and suggesting the most comfortable fit.”

And therein lies the rub—the idea that one woman could stand in for all women and represent the needs, preferences, and problems of her sex.

“Sorry, but I laughed (as did most of my colleagues) through the entire article,” he concluded.

But with an estimated global market value of $6.5 billion dollars—and growing—it’s Lawson who’s still chuckling 30 years later.

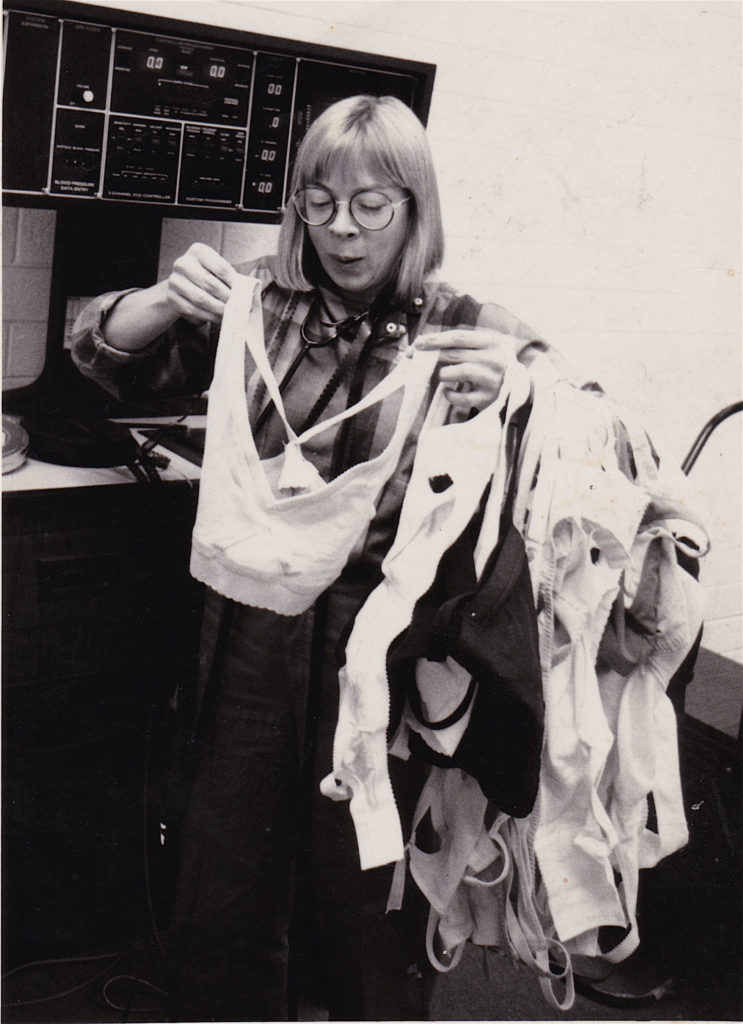

Since her landmark study was published in the journal Sports Medicine in 1987, Lawson has consulted for Champion athletics, running its bra lab and finds herself continually improving sports bras using science. It was not a career that existed when she enrolled to study historic costume design as a graduate student at Utah State University in the early ’80s.

“I’ve said many times, things happen in your life. Don’t judge them to be bad or good.”

While researching her thesis on knitting, Lawson’s main subject died, and so did her paper. Her major professor suggested she tack some questions onto a survey he was conducting so she could gather some data to write a thesis. We got back the data, Lawson says, and my questions had been mistakenly removed. “I thought I was becoming the poster child of the student who never finished.”

That error changed everything.

“I’ve said many times, things happen in your life,” she says. “Don’t judge them to be bad or good.”

Lawson was drawn to sports during a time when women weren’t always welcomed onto athletics fields. In high school, my basketball team still played by “girls’ rules,” she says. “It was all before Title IX. I was one of only two girls that took PE all four years.”

An early adopter of the Jogbra—the first modern sports bra made from two jock straps sewn together—Lawson recalls finishing marathons with bleeding nipples. “There had to be a better way,” she says.

During noontime runs with Deana Lorentzen, an assistant professor in the health, physical education, and recreation department, the two women wondered if anyone had ever studied sports bras before. Suddenly, Lawsons’ third thesis, “A Comparison of Eight Selected Sports Bras: Biomechanical Support, Overall Comfort Ratings, and Overall Support Ratings,” was born. Lorentzen co wrote a grant to fund Lawson’s study, which at the time, was the largest study to use biometric data and user feedback.

LaJean Lawson holds a handful of sports bras she tested during her landmark study she conducted as a graduate student at USU.

Their timing was auspicious.

Just a decade earlier in 1972, Congress passed Title IX, which mandated that women have the same access to educational opportunities as their male peers. That same year, Frank Shorter won Olympic gold while competing in the marathon, setting off the nation’s running boom. Bra manufacturers were quick to offer women garments to meet the growing demand, but most failed to incorporate biometric data into designs or focused on competitive athletes who tend to have smaller chests. The average woman was left out of the equation. Until Lawson’s study, the science on the matter broke into two camps: small biomechanical studies, and “debate over whether specially designed sports bras are necessary,” Lawson wrote in her thesis.

She recruited 59 women and filmed them jogging on a treadmill nude and in eight different sports bras using a 16 mm camera to determine breast displacement while exercising and to evaluate how well the bras performed across, and within, various bra cup sizes.

“I’m still amazed that we got funded,” Lawson says.

She credits USU administrators for seeing the project’s value even if it wasn’t clear to government watchdogs who gave the researchers a golden fleece award, arguing it was a waste of taxpayer dollars.

But as Lawson learned, size matters. So does breast density, shape, and the type of sport a woman plays. Running requires a different bra than ballet. The one-size fits- all T-shirt only really fits one size—why would sports bras be any different?

“There was a great sense of relief that someone was finally doing something,” Lawson recalls when talking about recruiting participants.

Her investigation identified common manufacturing pitfalls such as using the same design for larger cup sizes rather than creating additional support styles to meet women’s various needs. Straps can chafe, underwire can stab, materials can overheat. A sports bra is one of the most intimate garments a woman can purchase, Lawson says, and yet, there was no one really looking into ways to improve it. And it’s a design problem she has continued tweaking for the last 35 years.

Perhaps sports bra research seems trivial. But women often don’t want to draw unwanted attention to their chests when they exercise. This anxiety can create a psychological barrier to exercise—and that is a health problem.

“There was a great sense of relief that someone was finally doing something.”

“Many women don’t care,” Lawson says. “But many women do want to be modest. They want to have control over who has access to information about their breasts.”

When padded sports bras first hit the market, she wondered why women were interested in wearing a heavier, hotter product. An athlete training for the Olympics told Lawson she wears padded bras so that spectators focus only on her finishing times.

“I had to recalibrate,” she says.

Now in her lab, Lawson has women test various products and queries them about factors such as fit, style, comfort, and modesty.

Her work continues to evolve as the body positivity movement gains traction. The increase in numbers of women, regardless of their size, claiming their space in yoga studios and on the treadmill at the gym has given Lawson a new design problem to solve. But her initial work in this arena was slow-going. It took six months to get the first plus-sized participant in the lab and 18 months to get enough people to participate in a focus group.

“I want you to know you’re the first person to see me run without a shirt on,” one woman told Lawson.

It was an important glimpse behind the curtain. Lawson holds a doctorate in exercise science and understands the complexity behind the global obesity epidemic. There’s not one factor or one lever that needs to be pulled to solve it.

“Ensuring a woman has what she needs to get moving—the physical, emotional, and mental benefits of exercise—that’s my part,” Lawson says. “I’m happy to be part of the solution.”