USU Alums Deal With Being COVID-19 ‘Long-Haulers’ More Than 3 Years After Initially Contracting the Virus

Christine Maughan and Ashley Sheesley were both young, active, healthy individuals who now deal with extreme fatigue, migraine headaches, mobility issues, and a slew of other health problems

By Jeff Hunter ’96

Just a few years ago, Christine Maughan rode over 100 miles in Cache Valley’s annual Little Red Riding Hood women’s cycling event, then hopped back on her bike that evening and rode to a friend’s house for dinner with her teammates.

“The next morning, I was tired, but not that tired,” Maughan acknowledges. “I was an endurance cyclist. I did many 100-mile rides, and I enjoyed the century, actually. I think they’re lots of fun, which tells you something about my personality,” she adds with a small laugh.

Fast forward to June 2023. The Sunday morning after participating in the Little Red charity ride for the 12th time, Maughan slept until after 10. And instead of getting back on her bike, she only ventured as far as the living room couch the remainder of the day.

“I had profound fatigue,” she notes.

The Monday after wasn’t much better for Maughan — “fatigue, headache, nausea, probably a fever” — and this was after completing Little Red’s shortest route of 16.7 miles rather than the century ride. And on a recumbent trike with electric assist.

“I’m still struggling a bit in terms of daily functioning,” Maughan says. “All of the things that I think most people take for granted when you’re not chronically ill.”

Once a determined long-distance cyclist, Maughan has been robbed of that ability due to her status as what has become known as a “long-hauler” in terms of COVID-19.

The 40-year-old Utah State University alum, originally from Orem, tested positive for the coronavirus in the first full month of the pandemic. And while she was never hospitalized during her initial bout with COVID-19, she hasn’t felt anywhere near as good as she did prior to contracting it. Instead, she has been dealing with myriad symptoms, including difficulty breathing, fevers, heart palpitations, tremors, mobility issues, brain fog and debilitating fatigue.

“I used to be the type of person that would just push through fatigue, right? I was constantly going,” Maughan says. “If you get tired, you have another cup of tea or cup of coffee, and you go on with your day.

“I didn’t realize that there was a type of fatigue that you couldn’t push through. This is bad. This is very different.”

Harsh Realities

Ashley Sheesley is only 27 years old. And yet, the Centerville native already boasts a mobility arsenal that includes a cane, a walker, a wheelchair, and a disabled parking placard.

“It’s only a temporary one good for six months,” she says of the parking permit. “My doctors are happy to renew it, but they’re hopeful that there’s going to be some new treatment come out of all of this research that’s going to make it so I don’t need a permanent permit.”

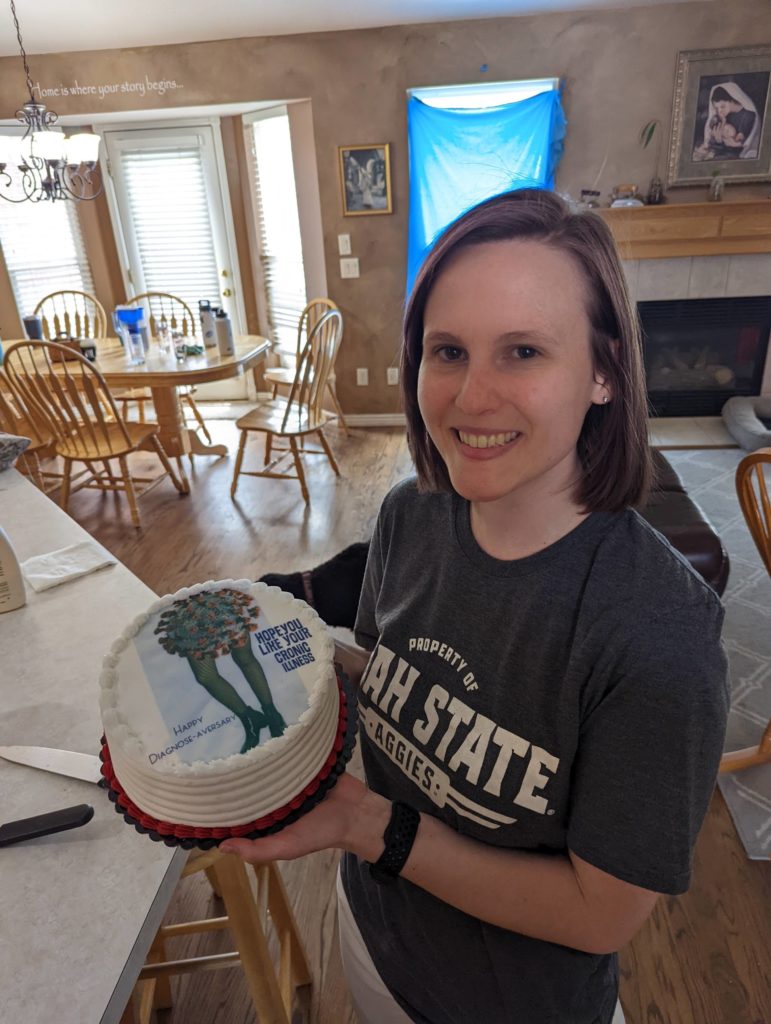

But three years into her battle with long-COVID, Sheesley is finding it increasingly difficult to be optimistic that she’ll be able to return to her pre-pandemic self. In addition to many of the same symptoms Maughan has been dealing with, she also has serious gastrointestinal issues. The severe fatigue and frustration after finding very few answers following dozens and dozens of doctor visits have taken their toll.

“After thinking I was going to get better after a few weeks, then a few months, I kind of just accepted that this is just the way it is right now and there’s not a cure,” says Sheesley, who graduated from USU with a bachelor’s degree in animal, dairy, and veterinary sciences in December 2018. “And honestly, that’s been kind of freeing in a way that a lot of people who aren’t chronically ill can’t really understand. It’s exhausting to go to bed every night and think, oh, maybe tomorrow it’ll be better. Maybe tomorrow all of this will go away.

“That’s just exhausting. And I came to recognize that there isn’t a cure right now, and that this is just the way it’s going to be for the foreseeable future. And that’s freeing, in a way.”

Ironically enough, when the COVID-19 pandemic really started to impact the United States in mid-March 2020, Sheesley was working for USU in the antiviral research lab in the Animal, Dairy, and Veterinary Sciences Department of the College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences. Involved with influenza research at the time, that group quickly pivoted to researching the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).

Intrigued by what was happening, Sheesley decided to apply for the master’s program in veterinary public health at Utah State because she was interested by how diseases spread among humans, animals, and the environment.

A month and a half later she got COVID.

She’s still not sure how. Possibly while camping or during a shopping trip, but Sheesley says that she, along with her husband, Drew, took all the precautions and constantly masked up. But Sheesley still ended up with the virus, and “pretty much had blackout on the COVID symptom bingo card,” she says.

Looking back, Sheesley admits that she probably should have been hospitalized at some point during her inaugural fight with COVID. At the time, she was too concerned about the financial cost to go to the emergency room even as breathing became more and more difficult, and one night she vomited every 45 minutes over an eight-hour stretch while suffering from incredible pain.

Sheesley survived and soldiered on, but unlike most COVID patients she didn’t get much better. Not even after nearly three months when she started her master’s program in the fall of 2020, or when she completed her degree and graduated in May 2023. All while dealing with a long list of ailments, including chronic fatigue syndrome, piercing migraine headaches, and myocarditis.

“I wanted to drop out once a semester, at least,” Sheesley admits. “It was hard. It was hard in a way that grad school is hard, but grad school with a chronic illness was hard in a way I was not prepared for. I ended up taking three years to graduate instead of two because I had to go part-time and take one summer off because I was so sick.”

Sheesley and Maughan became acquainted three years ago through their mutual battle with long-COVID, and stayed in touch through involvement in online support groups, patient advocacy initiatives, and studies.

An English literature graduate who lives in Logan with her husband, Steve Cracroft, and their daughter, Imogen, Maughan travels to Salt Lake City often to meet with doctors, many of them at the COVID-19 Long-Hauler Clinic at the University of Utah Hospital. She’s also part of an observational cohort with the National Institute of Health’s RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery) initiative.

The term “long-hauler” refers to people dealing with long-COVID symptoms, and at this point in time, not many people have endured a longer haul than Maughan. She first started feeling coronavirus symptoms in March 2020, and tested positive for COVID in April. Breathing became so difficult at times that she says several times she fully expected not to wake up the next morning after finally falling asleep. She’s contracted the virus two additional times since then, despite being fully vaccinated and extremely cautious.

Maughan gets so fatigued so quickly that she no longer drives outside of Cache Valley. And like Sheesley, the longtime cyclist, hiker, and skier has also had to apply for a couple of temporary disabled parking placards.

“That’s a real challenge, coming to know your own truth,” Maughan says. “Not everyone sees invisible disabilities, right? I look able-bodied, but sometimes when I go to Salt Lake for a doctor’s appointment or even just to the store here in Logan, I’m managing OK when I arrive, but I’m substantially more fatigued or have tremors or mobility issues by the time I leave.”

While the physical, mental, and emotional challenges have been many, Maughan says nothing has been harder to deal with than being a mother constrained by the harsh leashes of a chronic disease. Long-COVID has robbed her of many opportunities she otherwise would have shared with Imogen, who is now 11 years old.

“There are so many things that I used to do with her that I just can’t anymore,” Maughan says, her voice cracking with emotion. “In fact, early on, she would frequently ask me, ‘When are you going to get better? When are you going to be the mom I used to know?’

“Well, research gives me hope. And I’m incredibly lucky to have good physicians who have helped me a lot, who aren’t giving up. They’re determined to figure out how to help us.”

While Maughan has contracted COVID three times, Imogen has had it once, while her husband, Steve, has never had the virus. Maughan and Sheesley both know people who have died from COVID, have long-COVID worse than they do, or who have had COVID multiple times, recovered, and returned to normal lives.

They simply have no idea why they are in the position that they find themselves right now.

“COVID is just so random,” Sheesley declares. “This is the virologist in me speaking here, but it’s just fascinating to me how varied the individual response to COVID and long-COVID is. I can’t think of another disease that has a spectrum that has such a varied outcome.”

Sheesley now lives in Sunset, where she’s currently working two part-time, remote jobs, including an epidemiology internship with the Utah Department of Health and Human Services. And while she’s currently limited by her status as a long-hauler, she’s determined to live life as best she can while building a career working “within the infectious disease umbrella.”

“I don’t want pity; I don’t need pity,” Sheesley says. “What I want is for people to be aware that this is a real thing. And to recognize that while the state of emergency might be over politically, COVID is still here. And there are still risks. And this is an outcome that can happen.

“I had no risk factors. I was only 24. I was a runner, who exercised a lot and ate super healthy. There was nothing about me that would have made me a prime suspect for developing long-COVID after COVID, and so I want people to still be aware that there’s a risk. You don’t have to live in fear and constantly stay inside, but there are things you can do to live a normal life while still being careful.”

A Ride to Remember

The pandemic led to the cancellation of the Little Red Riding Hood cycling event in both 2020 and 2021, so Maughan didn’t miss out on the popular, 3,500-rider fundraising event during her first two years of dealing with long-COVID. But she was determined to get back in the game in 2022, which led to the purchase of her recumbent trike with electric assist.

Among the issues Maughan and many other long-COVID patients like Sheesley deal with is Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), a disorder that leads a person to feel faint or dizzy due to a low blood volume when they’re standing up.

“So, being on a recumbent bike is actually better for me because my body’s not having to fight gravity as much as it would be if I was upright,” Maughan explains. “Sitting down while I’m biking makes a big difference as far as energy expenditure.”

Maughan’s plan in the spring of 2022 called for her to ride Little Red with Imogen. But after training together for several months, her daughter ended up breaking her wrist shortly before the ride, leading to Maughan to try and navigate the nearly 17-mile route with a friend. And, while she was able to complete the course, the cost was pretty significant in terms of brutal fatigue and myriad other symptoms in the days afterwards.

However, despite understanding the likely ramifications, Maughan decided to give it another go this June because Imogen wanted to finish what she started in the spring of 2021. And blessed with a beautiful Saturday, the twosome left Lewiston at 10 a.m., headed south towards Richmond, then west to Trenton before heading back north across the Idaho border and returning to Lewiston. Their ride took about three hours, counting several casual stops around the course, which boasted a “Pedal in Paris” theme this year.

“I think some medication changes helped me out there this year,” Maughan says of the Little Red ride, which raises money to battle breast and ovarian cancer at the Huntsman Cancer Foundation. “And to be quite honest, my daughter is a slower cyclist than the friend I went with last year. So, it was more of a leisurely pace, which seemed to work better for me.”

But Maughan says she started feeling fatigue and other symptoms before she and her family even got back home, and that it took more than three days before she was able to get back to “baseline” as far as just feeling really bad, instead of “profound fatigue.”

“I still feel like it was worth it to do the ride; it was important to me,” Maughan proclaims with tears in her eyes. “I have missed so much of the last three years of Imogen’s life, to be entirely honest, with me being sick and sometimes having days when I’ve just had to spend entire days in bed.

“So, I have to try and seize the opportunities that I can.”