Overcoming Trauma: “It’s Not Always Rainbows in Life”

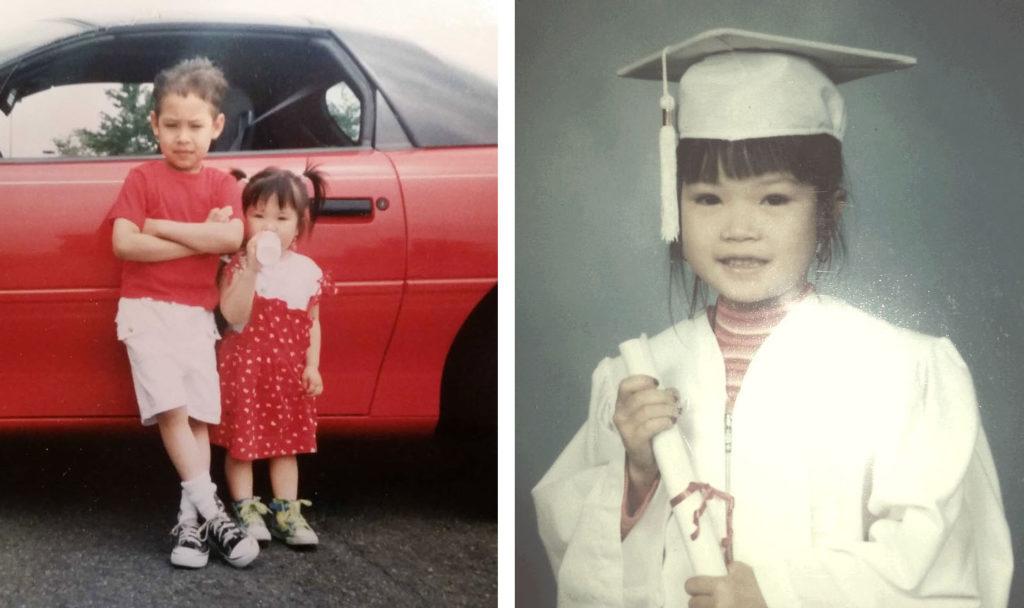

For most of us, it’s around five years of age when we’re still experiencing some of the earliest memories that may stay with us for a lifetime.

Visions of something like holding a puppy, playing with friends, or the first day of kindergarten can populate our minds for decades to come.

So, when Mary Phan shares one of her earliest memories of growing up in Trenton, New Jersey, the abrupt loss of innocence feels tragic to the listener, even after she explains, “At the time, it was my environment. I didn’t realize how bad that was. It just seemed so normal because I just grew up hearing gunshots all the time.”

“But to actually see it for the first time was just like, Whoa!” Phan adds. “It was very surprising, but I don’t know if it hit me until years later when I realized what actually happened.”

What happened was a 5-year-old Mary and her 8-year-old brother looked on through the window of their apartment as the members of two rival gangs faced off in the adjoining alley that was always littered with garbage like broken beer bottles and used syringes.

“They were arguing back and forth at each other when suddenly, one guy took his gun out and shot another dude’s brains out,” Phan recalls. “That was the first time I saw blood and death in real life. And it wasn’t my last time.”

And it wasn’t even the last time Phan experienced heartbreaking trauma at the tender age of 5.

Not long afterwards, Phan and her brother were playing video games with his friend, who was 18 years old, without their parents around.

“Looking back, there were so many red flags about that. But here was a super cool dude who had a Nintendo 64,” Phan says. “But when my brother took a bathroom break during the middle of gaming, the guy asked me I wanted a shiny coin. Of course, I wanted a shiny coin. I wanted to give to my brother.

“He said I could have it as long as I followed his rules,” she adds quietly. “I’ll spare you the details, but that was the first time I got molested.”

Phan, who is heading into her third year in the PhD program in Utah State University’s Department of Psychology, originally shared some of the difficult experiences from her youth with the USU community last fall during the 2021 Inclusive Excellence Symposium during a panel entitled “Living in the U.S.: International Perspectives Without the Rose-Colored Glasses.”

The personal stories Phan shared led to her being included in the annual Aggie Heroes event a few months later when she revealed the additional challenges of growing up poor and the racism she endured as one of the few Asian Americans her age in her community.

Phan’s father immigrated from Vietnam with his family when he was young, while her mother, the offspring of a Vietnamese woman and an American soldier, was adopted by a family in the United States. After her parents got married and had children, the Phan family moved every few years around the southern New Jersey-eastern Pennsylvania region, causing Mary to continually change schools.

“It was extremely isolating, especially when every day was spent answering questions like, ‘Why are your eyes so slanted?’ And ‘Are you related to Jackie Chan?’ or ‘Why is your face so flat?’” she recalls. “But as much as I was picked on for being Asian, I didn’t let that stop me from going to school with perfect attendance and working hard to get good grades.”

In addition, Phan was pressured into getting married at a very young age by her boyfriend, who was about four years older and needed to marry a U.S. citizen. She originally asked her mother if she could get married when she was 16, and after being told “absolutely not,” waited until she was 18 and no longer needed permission.

“I didn’t even shower that morning,” Phan says of her wedding day, that didn’t include any members of her family. “I remember my hair was still curved from the day before, and I just put it in a messy bun and my wedding dress was my junior prom dress. He didn’t shower, brush his hair either, and just threw on a very wrinkly suit.

“I remember when I said, ‘I do’ in the living room that I started bawling my eyes out because I knew that wasn’t what I wanted.”

More than a decade later, Phan’s parents still don’t know their daughter ever got married, much less the hardships she faced before she was finally able to leave the difficult marriage after four years.

“I’m at a place mentally now where I can process that, but they’re not in a mental place where they can process that in a healthy way,” Phan explains. “I don’t want them to feel bad or sad or upset.

“So, it’s just something that I’ve kept to myself, and then shared with everyone else but my family,” she adds with an awkward chuckle.

When asked if it was difficult to share some of her life’s most awful moments with a room of primarily strangers, Phan just smiles and declares, “I’m an over-sharer … I have a really weird personality where I’m so open about my traumas. And over time, it’s just become very easy. I feel comfortable sharing it.”

She adds, “I want to normalize that it’s not always rainbows in life. And the stuff I talked about at Aggie Heroes was only like 40 percent of stuff; I didn’t share everything.”

Now 29 years old, Phan started her higher-education journey at Bucks County Community College in Pennsylvania, then moved onto Temple University in Philadelphia, where she graduated in psychology in 2016. She then spent a year as an undergraduate research assistant at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia before deciding where to pursue her doctorate in school psychology.

Phan says she was drawn to Utah State because her research “aligned perfectly” with that of her advisor, Tyler Renshaw, an associate psychology professor who heads the School Mental Health Lab. Phan, who is also a health policy research scholar at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, is focusing her research on “implementing mindfulness-based interventions to underserved youth in public schools.”

Mindfulness is defined as “the basic human ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we’re doing, and not overly reactive or overwhelmed by what’s going on around us.” The use of different forms of meditation, short life pauses, and/or the use of physical activities like sports or yoga are some of the ways mindfulness can be implemented into our lives, and Phan hopes to increase accessibility to mindfulness practices and mental care services in schools.

“I didn’t know about any of these things until I was in college,” she says. “And that’s why I want to work with youth because they’re still so young, and you can share with them, ‘Hey, there’s a way to deal with stress or cope with whatever you’re going through.’

“Practicing mindfulness is free, so I really care about making it accessible to a lot of people. And that’s why I’m particularly stationed at the schools because I want them to have something that parents don’t have to worry about, like traveling to a clinic to drop their child off. The kids are at the schools already, so the framing of my thesis is how to teach teachers how to do mindfulness interventions so that they can teach it to their students.”

Phan quite literally wears her passion for mindfulness on her sleeve.

On her left shoulder, she has a large tattoo that includes flowers and a clock with the time of her birth, and Phan explains that the clock is there as “a reminder to always be present” because the definition of mindfulness is to “always be present and aware of your moment-to-moment thoughts.”

In addition, on her lower left arm, Phan has a Sanskrit tattoo of the enlightenment mantra, “om mani padme hum” which she says is a reminder of the path she is following as seen through a spiritual lens. Her lower right arm has a tattoo of a branch that represents the Buddhist goddess of compassion.

“This a reminder to be compassionate to everyone and realize that everyone is suffering in the lens of Buddhism,” she explains. “That’s a core value of mine. That even if people are mean or unapproachable, you always need to see things through a compassionate lens.”

Phan admits that early in her academic career, she was concerned that her tattoos might limit her graduate school opportunities or that she might be judged differently when doing field work in schools. But she also firmly believes that “having tattoos should become more normalized,” and in her most recent USU portrait, she chose a sleeveless shirt to show them off.

“New academic photo! I was so worried about my tattoos but decided to stay true to myself since it’s a huge part of my cultural background. Glad I did,” Phan declared in a pinned tweet on her Twitter account.

“They are important to me; they mean a lot to me culturally and are a reminder of where I came home,” she says. “… But they’re all based off of Buddhism and mindfulness practice, and that’s my research.”

By Jeff Hunter ’96

Portraits by Levi Sim