Laughter in Dark Times

Medicine is not considered a bastion of comedy. Many doctors work in high-stress, high-stakes environments where patient health is at risk. Where is the humor in that?

Lisa Gabbert, associate professor of English at Utah State University, argues the emotional suffering in the medical profession creates the alchemy for humor to thrive.

“People think of medicine as based in science and therefore not having culture,” she says over a Zoom call in January, “but medicine is as much culturally inflected as anything else.”

Gabbert began considering material for her latest manuscript Suffering and Laughter: The Medical Carnivalesque among Physicians two decades ago when her husband was in medical school. He knew folklore when he heard it and began feeding Gabbert jokes from the field. It was a rare glimpse behind the exam room curtain into a world often privy only to medical insiders—one filled with puns and absurdities more at home on episodes of Scrubs than ER.

“Dark humor is where I started,” Gabbert says. “Physicians sometimes use gallows humor or dark humor.”

But they are not limited to it.

Doctors are often punsters, she says. “It felt like there was more to get at.”

Gabbert has been collecting jokes and stories from interviews with physicians and mined the internet for comedic lore found in social media and websites like Gomerblog. She noticed common threads. For instance, doctors make fun of each other’s specialties and poke fun of stereotypes in medicine. A longstanding joke:

How does an orthopedist hold an elevator door? With his head. How does an internist hold the door ? With his hands. How does a hospital administrator hold the door? With someone else.

Are you laughing? Probably not.

“These jokes are very esoteric,” Gabbert says. “They are very funny to physicians.”

She found doctor humor often contains an anti-authoritarian bent. It’s not uncommon to find jokes about hospital administrators (see above) or about the systems that constrain their actions. Physicians recognize the challenges governing their work and find a way to expose them and lament them through laughter.

“It’s taking these very valued, officially held ideas that are sacred—or held to be at the time—and turning them on their head,” Gabbert says.

In 2009, she coined the term “medical carnivalesque” with physician Anton Salud to reframe physician humor to “characterize the subversiveness, inversions, and resistance found in medical humor,” Gabbert writes in Suffering and Laughter: The Medical Carnivalesque Among Physicians. “I also argue that suffering is an essential component of the medical carnivalesque.”

“A lot of people don’t think about the fact that physicians might suffer,” she says. “It’s almost like unless you are a patient you can’t suffer.”

Instinctively, we know that this is not true. But the physician’s job by trade is to care for patients, a role where they find themselves focused on relieving the suffering of others and potentially unable to address their own. Physicians are constantly exposed to low-grade suffering as part of the profession, from the grinding nature of the training and work to the outcomes. Trauma may occur when one makes a mistake that injures another human or from failing when one thinks they should have succeeded. In recent years, there has been an increased awareness of stark depression, substance abuse, and suicide rates of physicians. And depending on where one works, admitting to personal problems can affect one’s livelihood and ability to get help.

“Taking time for oneself is often seen as taking time away from a colleague because it means that one’s colleague must cover the sick doctor’s patients,” Gabbert says. “They fight for their patients’ health and wellbeing, but the concept of sickness and death lurks in the background.”

This tension goes somewhere and often it manifests in humor.

“One thing humor does is it transforms,” Gabbert says. “It expresses anxiety and frustration, and it transforms situations from whatever they are into one where that suffering gets relieved. Their work breaks a lot of normal everyday taboos. What the humor does is take situations that are not ideal and temporarily transforms them into something else.”

Gabbert was working on this project when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. She noticed physicians sharing memes about the crisis highlighting the limits on personal protection equipment (PPE) and broader public health issues like whether or not the general public was complying to wear masks to prevent the spread of infections.

These issues directly affect them, Gabbert explains. “What is different now is physicians using humor like memes in public to address aspects of the coronavirus.”

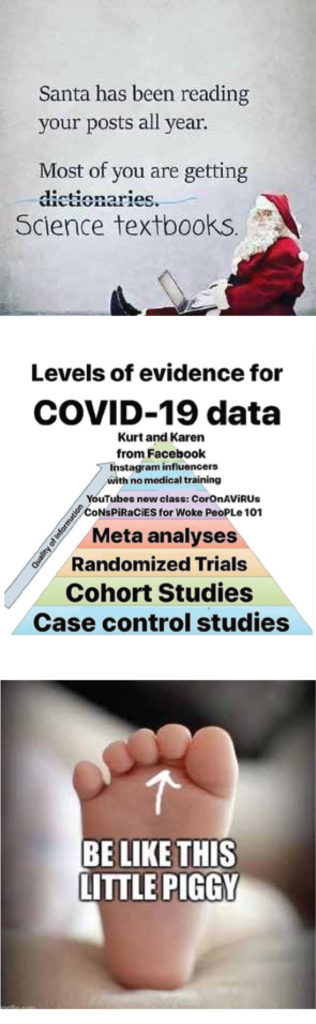

She began cataloguing the jokes online and identified how doctors have used humor to cope and to inform about work conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. She found two primary themes: humor that highlighted bad medical advice and jokes about physician safety. Her findings will be published in a forthcoming article “Humor in the Time of Pandemic: Coronavirus and Expert Health Knowledge” next summer in the Journal of Folklore Research.

Often, doctor jokes are told by doctors for other doctors. They may be critical of problems within the medical system. COVID-19 upended that.

“Instead of poking fun at institutionalized knowledge they are defending it,” Gabbert says.

For instance, physicians started posting memes addressing the contrasting advice between good health care practices offered by medical experts with those proposed by relatives on Facebook. They poked fun of the country’s woeful lack of science education:

“Humor by its nature crosses boundaries and is transgressive,” Gabbert says.

Humor is a way people can say things that need to be said while avoiding the typical minefields that might trip them up. It may make things easier to hear as well.

Physicians frequently posted about the discrepancy between how doctors were treated in the early days of COVID-19, such as with applause or yard signs declaring their support for healthcare workers, with how they found working conditions in their hospitals such as their limited supplies of PPE.

“They felt directly affected by the choices the public was making, since non-compliant health-related behavior made their work more difficult by increasing the number and severity of patients, as well as increasing the dangers to their own personal health and safety,” Gabbert writes in the article. “And yet providers had no choice but to take care of patients since this is their job. It is not surprising then, that humor and memes about COVID-19 began to circulate, many of which took aim at anti-science or anti-medical rhetoric, folk beliefs, perceived government and institutional ineptness, and public behavior that contradicted or was antithetical to recommended health guidelines.”

“Humor by its nature crosses boundaries and is transgressive.” – Lisa Gabbert

The COVID-19 pandemic arrived at a time of deep political divisions in the country and during an era where conspiracy theories abound concerning political leaders and the origins of the coronavirus. It did not help that the national response to COVID-19 stumbled out of the gates from a lack of accurate tests to providing enough safety equipment for first responders.

“Certain forms of folklore thrive in such chaotic environments, particularly rumor, gossip, conspiracy theory, and legend, which fill in knowledge gaps with ideas and information that provide folk explanations for what is going on,” Gabbert writes. “ . . . The larger issue, however, is the broader one of competing forms of knowledge/power. The U.S. is currently in the midst of an information war and the pandemic is merely one front.”

“I generally think [physician humor] is a healthy outlet,” she says. “But as a folklorist, it’s not our job to say something is good or bad, but rather why does it exist?”

What does the current state of doctor humor say about the profession at large?

“I think there is room for improvement in terms of support for physician wellbeing and self-care,” Gabbert says, “especially in the arena of mental health.”

By Kristen Munson

Top illustration by Liz Lord ’04.