The Art of Science

Marissa Devey is a child of the suburbs.

A place where sidewalks cordon off neatly trimmed grass and flowerbeds are designed to look wild. In school she learned of climate change and it seemed like an intractable problem far away. And then her junior year at Utah State University she met Jessica Murray, a Ph.D. student in ecology, at the science writing center.

Devey, a graphic design major, reviewed Murray’s grant application. She considers her lack of science background an asset when working with scientists. It forces them to ditch the jargon and distill their work in a manner people can easily digest. “Jessica was telling me about her work, and I was just kind of enthralled by it,” Devey says. “It felt like something more people needed to know about.”

Murray’s project is in the cloud forest of Monteverde, Costa Rica. A near constant mist cloaks the high-altitude rain forest with moisture and creates a rich palette of green as

plant life sprouts from moss-covered trees. The Monteverde Cloud Forest Biological Reserve is famous for its wildlife, including howler monkeys and the resplendent quetzal, an emerald bird ecotourists flock to the region to see. But Murray studies a less glamorous part of the canopy: the soil.

Decaying organic matter captured in the branches above the forest floor form soil in the canopy over time. Canopy soil serves as habitat for other animals and plants and regulates the flow of nutrients and water to the ground below. It also affects the global carbon cycle. Microorganisms break down nutrients and respirate, locking carbon into the soil from the atmosphere. Murray’s project studies how changes in soil decomposition from climate change affect that cycle. Because the forest is changing.

“Artists can take concepts and make people care about them in a way that they wouldn’t care about before. The things that we learn from science aren’t going to do us much good if we don’t put the humanity back in.” – Marissa Devey

As global temperatures warm, the clouds keeping the soils and plants moist are lifting to higher elevations. Rainfall is less predictable. Extreme flooding is increasing. It’s a feedback loop of change affecting the ecosystem in the trees from orchids to the quetzal. And that could mean species that have adapted to live in the cloud forest could chase the clouds to higher elevations—if they can.

“You can only go so far up the mountain before it’s gone,” Devey says.

She was captivated by Murray’s research and suggested she create an illustrated field guide to explain the forest’s health to people who may never visit it. Devey funded the project with an Undergraduate Research and Creative Opportunities (URCO) grant and as one of USU’s first Caine Fellows. Last May, she followed Murray to Costa Rica and up into the trees while she collected temperature, moisture, and respiration levels of canopy soil.

“I like the idea of science and art working together,” Murray says. “I think we have a lot to learn about connecting with people. In science, we really value objectivity.”

Scientists are supposed to leave their passion out of their data. Scrub it of biases that lead to faulty conclusions. Artists like Devey can provide the emotion that gets sucked out of a dataset. Art can communicate urgency. And beauty. And loss.

“Artists can take concepts and make people care about them in a way that they wouldn’t care about before,” Devey explains. “The things that we learn from science aren’t going to do us much good if we don’t put the humanity back in.”

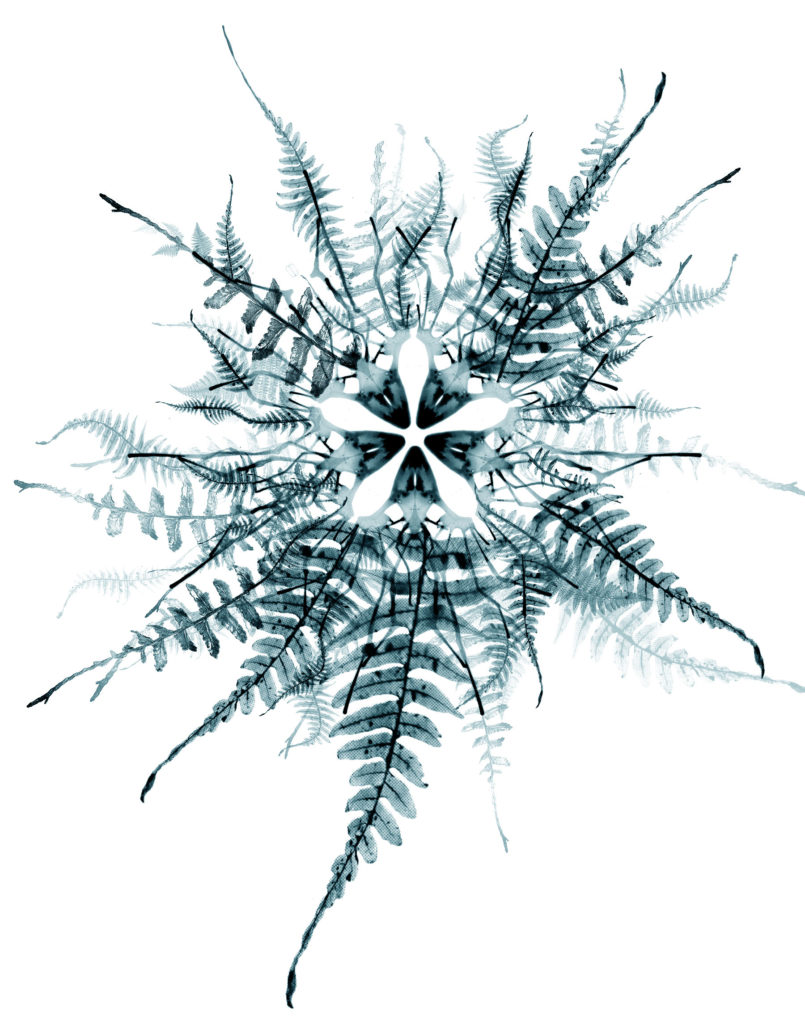

Vines. Highways of green wrapping around trees in the cloud forest reminded her of the body’s vascular system. Devey’s project “Between Earth & Atmosphere: A Field Guide to Carbon, Climate, & Costa Rica’s Cloud Forest Canopy” translates the health of the cloud forest into something most people can understand—their bodies. Anyone who has had a fever knows how sick you feel with just a two-degree difference from normal.

“The problem with climate change is this whole matter of scale. You hear about all these problems and then you go outside and it feels so enormous.”

“Climate change is a really personal thing for all of us whether we realize it or not,” Devey says. “The problem with climate change is this whole matter of scale. You hear about all these problems and then you go outside and it feels so enormous.”

Walking in the cloud forest, Devey noticed how she physically responded to the place. There is no air conditioning. You sweat. The roads are bumpy. You are jostled about as you move, she explains. “Here, we protect ourselves from the elements. We are comfortable.”

And she suspects that comfort may prevent us from noticing small changes. Small changes that can lead to bigger ones. Like the absence of clouds and birdsong.

-Kristen Munson

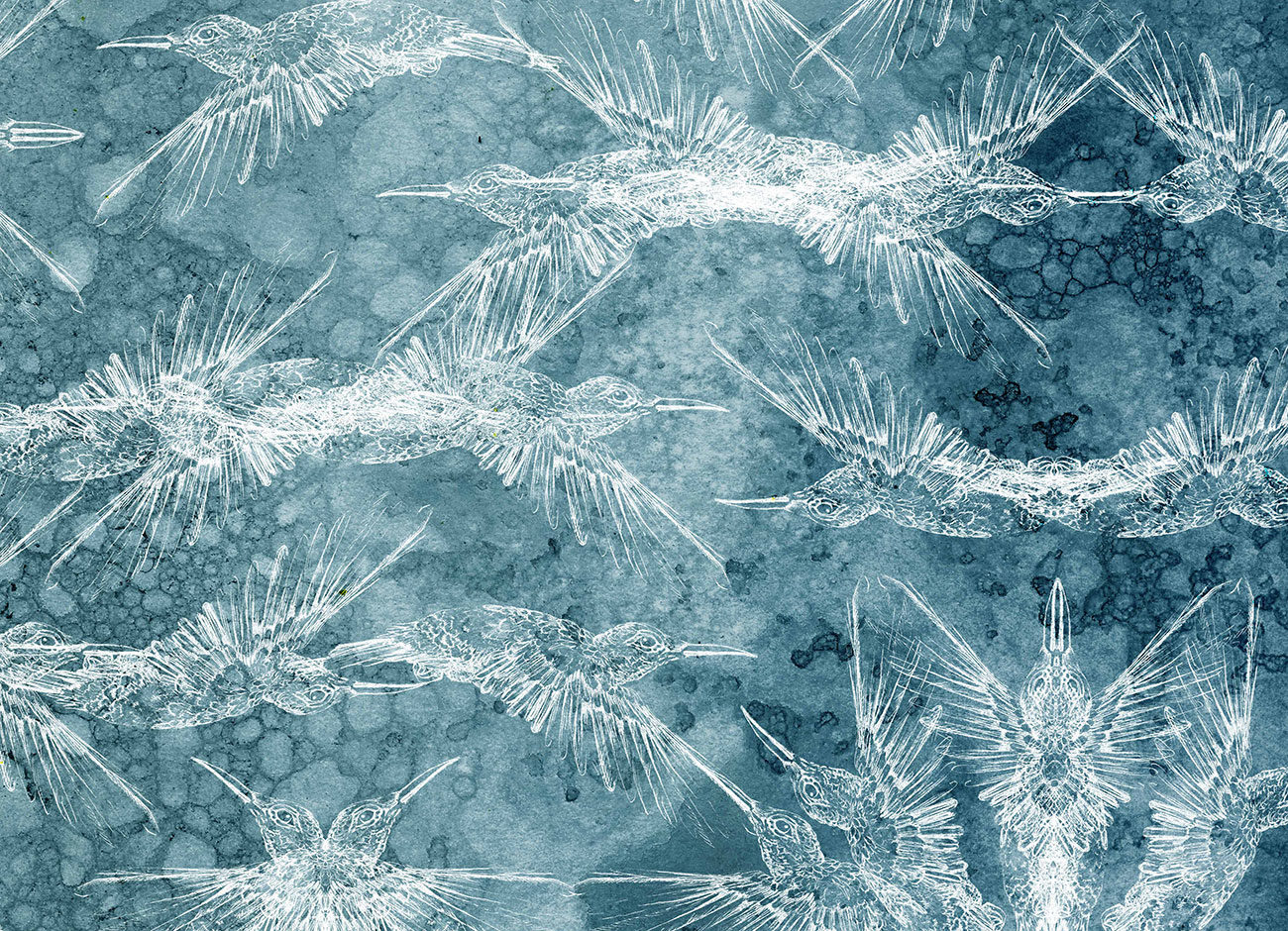

Marissa Devey traveled to the cloud forest of Monteverde to illustrate a field guide of its health. Image by Marissa Devey.

Between Earth & Atmosphere

Excerpts by Marissa Devey ’20

I feel like I am being swallowed as I tread on ground soft as a tongue, licked and lapped up by leaves the size of umbrellas, the air around me like a warm exhale. I clamber over fallen limbs and duck under low-hanging vines, following Jessica deeper into the cloud forest of Monteverde, Costa Rica. Our destination is up.

“That looks like a good one,” Jessica says, pointing to a tree that the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve’s array of researchers have named Tarantula. The tree arches high above us, limbs shaggy with ferns, orchids, and vines. The lower branches I see must be nearly 50 feet above us. The highest branches recede up into the mist.

Jessica unpacks a slingshot that looks more like an archer’s longbow and takes careful aim at a branch 150 feet up, leveraging every bit of weight on her lean body to pull the slingshot tight. She lets go. With a sharp wzzzzk!, a small weighted bag sails high into the canopy, trailing a thin black cord behind it that we’ll use to pull our climbing rope up and over the target branch.

The Monteverde cloud forest is home to hundreds of species of orchids and animals that are specially adapted to thrive there. But the rain forest is changing with the climate. Image by Marissa Devey.

I climb, and the climb feels like a dive into the ocean—like I’ve been merely looking at the water’s surface, its depths obscured by ripples and shadows, and now I’ve taken the plunge—immersed myself in an entirely different world made of clouds and eerie, beautiful birdsong. I climb higher, past red roots wrapping branches, trees growing on trees. Seedlings of the giant Matapalo tree sprout high in the canopy their roots creeping down the host tree like tiny bright blood vessels. Thickening into arteries, weaving muscle fibers that squeeze tight around the host tree’s trunk till Matapalo’s roots are tough and unyielding as bone.

I used to picture scientists as people in long white lab coats, surrounded by sterile white-tiled spaces and holding test tubes over bunsen burners. But the scientist hanging from the tree branch beside me wears a raincoat and a climbing harness. Her gloves aren’t latex; they’re for gardening. Jessica carries her laboratory in a rain bag clipped to her side, and we’ve just arrived at her workspace: an overgrown tree branch almost a hundred feet above the forest floor. Despite our long, soggy journey up to the treetops, we’re not here to observe monkeys or survey tropical bird nests. We’re here for the dirt.

Jessica pauses before the descent back down, absentmindedly brushing away a mosquito. “Do you hear that?” she asks me. A bird’s song, like a long sigh, rings around the canopy. “That’s a quetzal. I think there’s a nest close by.” I’ve been hoping to catch a glimpse of the resplendent quetzal ever since I arrived in Monteverde, and I twist around eagerly on my rope, straining my eyes for a flash of crimson and emerald feathers between the trees. No such luck, but I can still hear the sighing song. We hang in the tree, waiting.

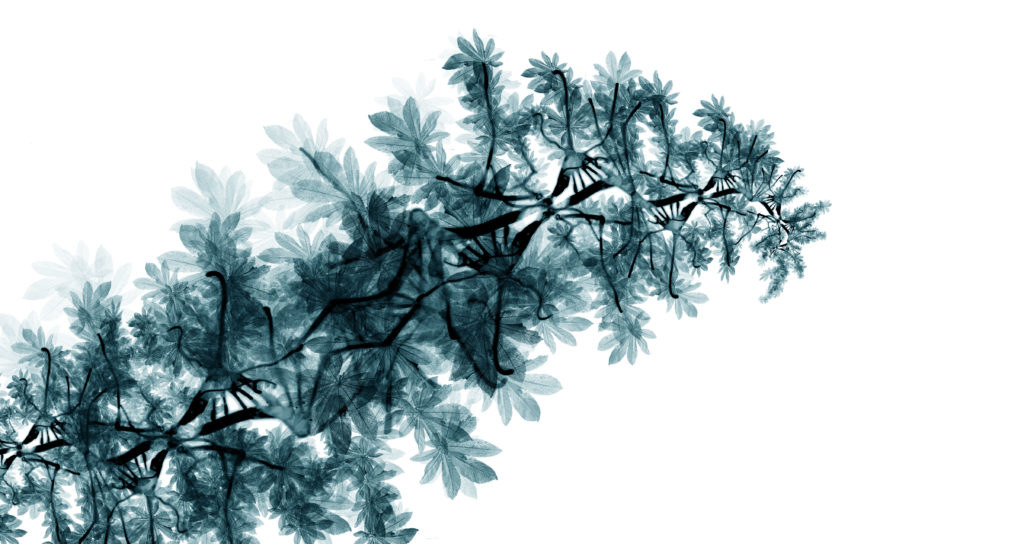

Marissa Devey visited a laboratory in the tree canopy of Monteverde, Costa Rica. She likens the health of the cloud forest to the health of the human body: an interconnected community of microorganisms. Image by Marissa Devey.

The cloud forest is never quiet. Water drips, bell birds call, and the branches overhead buzz with life. Draped in green cascades of epiphytes, these branches are home to a stunning array of creatures, some of which spend their entire lives without ever touching the ground. Many of the species that live in the canopy are so keenly adapted to this world between earth and atmosphere that they don’t exist anywhere beyond Monteverde’s cloud forest.

Humans rely on “specialist” relationships, too. Our skin, lungs, and gut provide habitat for an array of bacterial cells, which are estimated to outnumber our own body cells ten to one. These microorganisms influence nearly every aspect of health from digestion to brain function. What would happen if this microscopic community changed?

Humans rely on “specialist” relationships, too. Our skin, lungs, and gut provide habitat for an array of bacterial cells, which are estimated to outnumber our own body cells ten to one. These microorganisms influence nearly every aspect of health from digestion to brain function. What would happen if this microscopic community changed?

“I haven’t done this for a while.” Jessica breaks the silence. “Just hanging in the canopy, watching the trees. I usually get so caught up in what I have to get once up here, I don’t take the time to look around. It’s nice to just sit for a while and listen.”

“Are you ready to go back down?” I ask. She smiles. “Not yet.”

I’m ok with that. We’ve got a long journey back down to the forest floor and a long walk with heavy packs through mud and rain back to the field station. We’ve got work to do. And big questions to address. But for a moment it’s good to just hang in this remarkable place between the earth and atmosphere, listening to the quetzal’s sigh.

Marissa Devey is a USU senior majoring in graphic design. You can see more of her work at www.deveydesign.com. Between Earth & Atmosphere is available for purchase at the cost of printing.