Navigating the Unstable Waters of Lake Powell

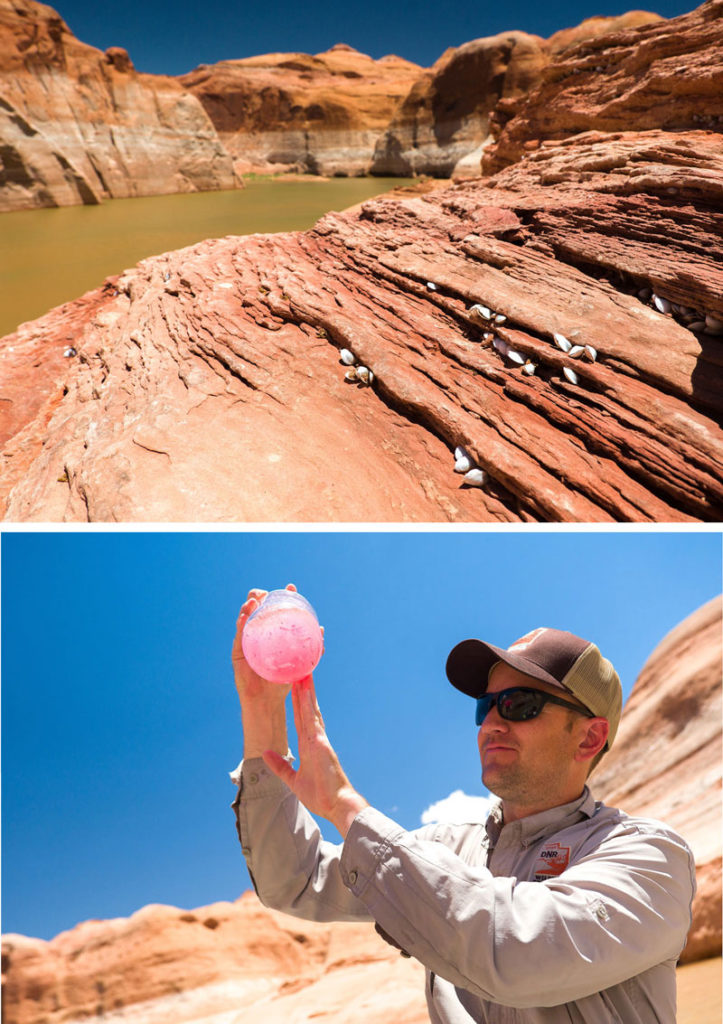

Two decades of western drought have slowly drained Lake Powell, revealing canyons and petroglyphs not seen since the 1960s when the reservoir first filled the desert floor.

While patrolling the water for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources this winter, Dan Keller ’08, M.S. ’13 saw the top of a stone arch boaters once easily floated over. People hike underneath it now.

The aquatics biologist recently took over managing Lake Powell’s fishery from Wayne Gustaveson who spent 45 years building the lake’s angling reputation — an important economic engine for the state.

Anytime during the year, you will see fishing boats heading down to Lake Powell and stopping and getting gas and using restaurants, Keller says. “Maintaining the excitement about the fishing there is my priority.”

Gustaveson wrote a weekly fishing report (he still does) that taught a lot of people how to be successful there, Keller says, admiringly. While he sees promise in holding fishing tournaments to boost tourism, Keller believes the lower lake level provides opportunities for people to also explore formerly underwater places by kayak or hiking.

“People are adaptable and people find opportunities where they are,” he says. “I think that is going to be the story of Lake Powell and the Colorado River in the future. I’d love to see the big snowstorms of the 80s come back. But if they don’t, we are going to have to do things differently with water.”

That day may come soon.

Lake Powell has always fluctuated as spring snowmelt flows into rivers and into the lake, flooding the margins and creating nursery habitat for young fish. By June, the water begins to drop. The level changes again as water is released into Lake Mead. Good water years make the bad ones easier to endure. And lately, the bad water years keep coming.

“2018 was good,” Keller recalls. “The water came up over 40 feet, but it’s just amazing how quickly it went down. … Hopefully we can get another good year like that — quickly.”

In March, Lake Powell dropped below 3,525 feet, placing hydroelectric power for millions at risk. Even forecasting reservoir rise is trickier as drought has parched watersheds, leaving dry soils that soak up more snowpack runoff. And low, relatively stable lake levels create conditions where invasive Quagga mussels thrive, which can alter the lake’s food web as they filter out zooplankton, starving some species of young fish.

“It’s just another competitor for a limited resource,” Keller says.

His path to managing the fishery begins while stationed at the Baghdad International Airport during a tour of Iraq with the National Guard in 2003. Keller watched carp in the canals and thought about catching shiners in cups as a kid camping in the San Rafael Desert. Sport fishing as a teenager at Lake Powell. He knew he wanted to do something he was passionate about when he returned.

Keller earned his associate at USU Eastern (formerly the College of Eastern Utah) and then studied conservation and restoration ecology in Logan. Keller spent 14 years as DWR’s native aquatics ecologist in Price, working on river restoration and native fish habitat in the Colorado River Basin.

“Not only do 40 million people depend on the water and that system, but a lot of wildlife and lot of fish,” he says.

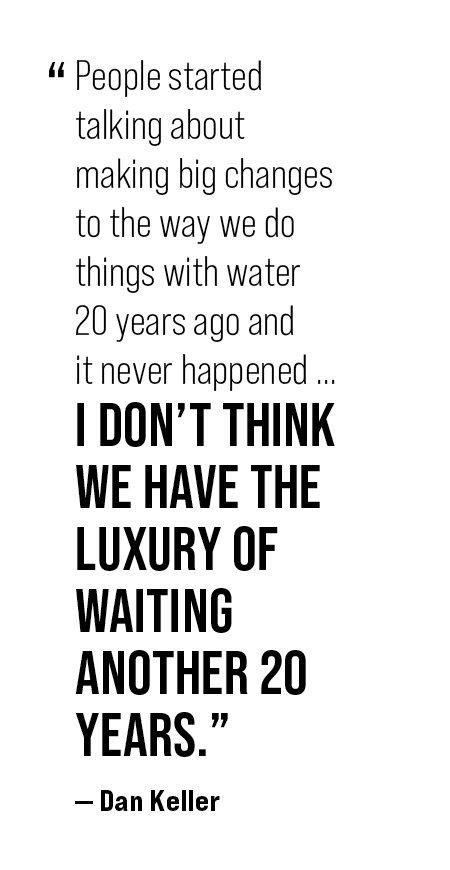

At Lake Powell, Keller alternates spending days on the water, taking depth and temperature profiles at monitoring stations and collecting zooplankton for analysis in the lab. The data help fishery managers predict which species can be fished and which need more protection.

“That is what fish management is all about — getting good biological data and making sound harvest and limit recommendations and ensuring that the anglers are having a positive influence on the fishery,” Keller explains.

He hopes anglers also help improve data collection by using citizen science apps to record their catches and wildlife observations that automatically populate scientific databases. He also wants people to keep coming to Lake Powell. To see that things have to change. We have to change.

“It’s daunting,” Keller says. “If you look at the Great Salt Lake and what’s happening here in northern Utah or the Colorado River Basin and what’s happening at Lake Powell, it’s just a reflection of how we are using water. And what ends up at these terminal bodies of water is a good indicator of things to come.”

He worries that if Utahns don’t learn about steps to reduce water consumption or support actions that promote it, these problems will get passed on into the future.

“People started talking about making big changes to the way we do things with water 20 years ago and it never happened,” Keller says. “I don’t think we have the luxury of waiting another 20 years.”

By Kristen Munson

Photos By Levi Sim