Mountain Man: A Career and Life at Mount St. Helens

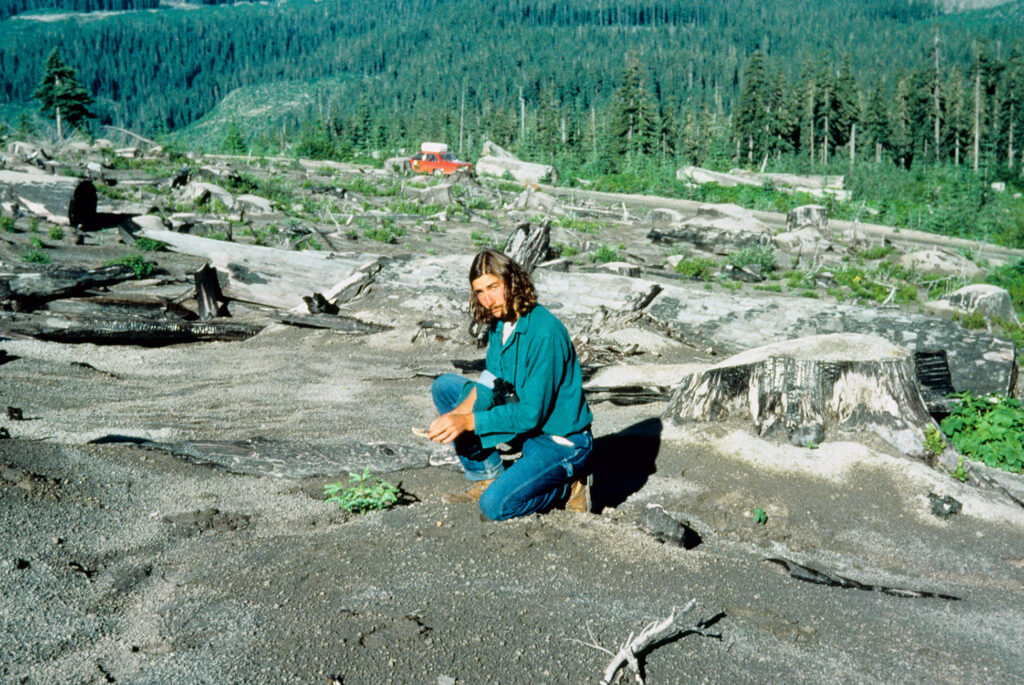

Charlie Crisafulli was a 22-year-old undergraduate student at USU when he began conducting research at Mount St. Helens just months after the May 1980 eruption

By Jeff Hunter ’96

Calling it love at first sight might be a little strong, but Charlie Crisafulli’s inaugural view of Mount St. Helens was certainly one of strong attraction.

It was the summer of 1978. And Crisafulli, a native of New York state, and a couple of friends had converted a Ford Econoline van into a camper and drove north into Quebec. The trio then fished, hiked, and camped their way west, venturing into as many Canadian provinces as they could before reaching British Columbia. The young men then headed south into Washington where they encountered the mighty mountains of the Cascade Range on their way to Oregon.

“I remember seeing Mount St. Helens off in the distance as we drove; I didn’t even step foot on it,” Crisafulli recalls of the massive stratovolcano that would end up dominating the next four decades of his life the way it dominates the landscape of southwestern Washington.

“There’s a number of places along I-5 where you get great views, and I can remember looking over to the east and she popped up above everything else in all her glory. It was a really beautiful, warm day, and the mountain was snow clad and perfectly symmetrical.”

Crisafulli adds: “When I got back home that fall, I said to my parents, ‘You know, I really need to go out West.’”

Much like Theodore Roosevelt, who also grew up with a deep appreciation for the flora and fauna of his native New York while later developing a passion for the landscapes and wildlife of the American West, Crisafulli soon did just that. After successfully applying to Utah State University as a transfer student from a college in New York, Crisafulli headed west again to continue his education.

At the time, he knew very little about Utah and wasn’t even entirely sure exactly what his field of study was going to be.

And what Crisafulli certainly didn’t know when he arrived in Cache Valley is that due to his enrollment at Utah State and his subsequent association with a USU professor, he would be returning to Mount St. Helens less than two years after his first glimpse of the 9,677-foot mountain.

Only this time, it was more than 1,300 feet shorter and no longer “perfectly symmetrical.”

Lessons from Nature

It’s one of those moments that always shows in a montage presenting the biggest news stories of the ’80s. Along with major moments like the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan, the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster and the fall of the Berlin Wall can be found the eruption of Mount St. Helens. And since it took place on May 18, 1980, it’s arguably the first noteworthy event of the decade, one that means many people of a certain age still vividly remember where they were or what they were doing when the mountain blew its top.

But, ironically enough, Charlie Crisafulli isn’t one of them.

“I definitely have run into a lot of people who have commented on where they were that day, whether they witnessed the eruption on television or had an actual view of it,” says Crisafulli, who retired in 2021 after being employed by the U.S. Forest Service as a research ecologist for 32 years. “But I wasn’t there at that particular time. I think I was in Wyoming — but it was a Sunday, so we could have been back in Logan — but we were working on a big project near Kemmerer that summer.”

Crisafulli’s involvement in that project, a mine reclamation study located about 50 miles outside of Kemmerer, Wyoming, came about due to an emerging relationship with James MacMahon, the longtime professor and College of Science dean who retired from Utah State in 2014. One of the first classes Crisafulli took at USU was a herpetology course from the man he refers to as his “No. 1 mentor,” and that led to an ecology class with MacMahon and many other opportunities, including a job at USU’s Ecology Center.

“We were enormously close,” Crisafulli says of MacMahon. “There’s no figure in my professional life who stands out as such a pillar as Jim MacMahon. He was instrumental and, in some ways, I feel largely responsible for my career and my whole experience because of the nurturing and mentorship that he provided.”

That relationship resulted in Crisafulli being invited along when MacMahon took a group from Utah State to begin conducting research at Mount St. Helens in September 1980. Just 22 years old at the time, Crisafulli’s first-ever helicopter trip was above the incredible devastation wrought by the eruption, which killed 57 people, blew over or killed nearly 150 square miles of forest, led to massive debris avalanches and devastating floods, and buried the once green landscape with a heavy coating of gray ash.

Seeing the lush forests of the Pacific Northwest abruptly give way to dead, scorched trees and then the stark, barren topography of what became known as the Pumice Plain on the northern slopes of Mount St. Helens was an eye-opening experience for Crisafulli.

“I was like, ‘How could this be? How could this possibly have happened at this scale?’” Crisafulli recalls thinking. “It was so awe-inspiring and compelling. And I knew at that moment I was looking at something that was profound and moved me to my core. I was frightened by it, and I was inspired by it. There were a host of emotions running through me. And at that time, I was just a kid and had no idea those formative experiences would be foundational and end up being a lifelong career that I’m still involved with today.”

During that first fall after the eruption, the road system in the vicinity of the mountain had been all but obliterated, leaving helicopters as practically the only way to reach the area. Even then, the pilots were instructed to keep their rotors spinning, leaving researchers like Crisafulli only about 10 minutes to collect samples and record their observations before taking off.

But Crisafulli embraced those early scientific opportunities with such enthusiasm that MacMahon ended up asking him to be the “Mount St. Helens kid” and spend as much time as possible spearheading many of Utah State’s research efforts. He wholeheartedly accepted, annually spending at least five months a year in the Mount St. Helens area while finishing up his undergraduate degree and moving into a position at the Ecology Center in USU’s Department of Biology, where he was employed from 1983-1989.

It was in the spring of 1989 when the perfect job opportunity for Crisafulli emerged: a full-time position with the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station as an ecologist at Mount St. Helens. He said leaving Logan, Utah State, and influential friends like MacMahon led to “a lot of tears,” but once the job was offered, Crisafulli and his family soon relocated to southwestern Washington, eventually settling in the small town of Yacolt about 35 miles northwest of Portland.

By the time he retired from the USFS in 2021, Crisafulli estimated he had spent more than 3,000 days and/or nights out in the field at Mount St. Helens, the majority of them at large camps he would supervise, often involving more than a 100 scientists and students from various agencies and colleges, including Utah State University.

In an essay published in 2008 entitled “Change, Survival, and Revival: Lesson from Mount St. Helens,” Crisafulli detailed how he spent his time on the mountain, “sampling biological populations throughout the volcanic landscapes, and hundreds of days more hiking, photographing, camping, skiing, and snowshoeing with family and friends.”

“This work has been intellectually and physically exhilarating, while grounded in dust, grit, fatigue, and great camaraderie,” Crisafulli continued. “In order to really learn what nature has to teach, we have to immerse ourselves in the natural world and see it from the perspective of individual plants and animals. We have to get to know the whole cast of characters, pay detailed attention to their activities, and unravel the tangle of factors that influence them. Through this practice, this immersion in field observation, we can begin to understand the relationships among living organisms and their environment. It’s also a way to explore how we, as humans, fit into the natural world.”

Life Goes On

Mount St. Helens is still the most active volcano in the Cascade Range. And while there’s never been another eruption anywhere near the magnitude of the one in 1980, the mountain is still prone to earthquake activity and eruptions on a smaller scale. However, those instances were much more common in the early ’80s, which led Crisafulli to experience some of his most frightening moments at Mount St. Helens.

Once he was leading a Utah State crew in the northwest sector of the blast area, about nine miles away from the volcano’s crater, when a helicopter suddenly showed up. The group had been out of radio contact, so the helicopter was sent to let them know that they needed to evacuate the area immediately due to increased seismic activity and gas emissions.

“Nine miles might sound far, but keep in mind that during the eruption, all life that wasn’t beneath the soil surface perished within seconds at that location,” Crisafulli notes. “We were directly in the line of fire.”

He was with another USU crew in 1983 when there no precursors of potential activity, but suddenly they heard thunderous rockfalls of the crater followed by “a big, dark, dark plume” of ash rising above the volcano.

“I can just remember us hightailing it as fast as we could, running a few miles out of there, across the Pumice Plain, to our vehicle,” Crisafulli says. “I kept looking in the rearview mirror around every bend to see what that plume was doing. There ended up being nothing life-threatening about that event, but it certainly was a reminder that this volcano is not at rest, and we need to be on guard.”

Needless to say, after spending four decades in the immediate vicinity of an active volcano, Crisafulli has learned a few things. And now that he’s “retired,” he’s determined to share that knowledge with others while learning even more about what happens to the biological communities in the area following an eruption. He regularly travels to the sites of other volcanic eruptions in remote locations like Alaska, Iceland, Chile, and Argentina to introduce studies and projects that he first set up in southwestern Washington.

“To what extent are the lessons gleaned from Mount St. Helens applicable or universal to other volcanic settings? There’s a lot that’s random or contingent upon other factors, but is there some level of predictability and universal application across settings?” Crisafulli queries. “The beautiful thing right now is that I’ve got to the point where I really need to know the answers to those questions. That is where I want to go with my career. The next step is to take the lessons from St. Helens and see how they hold up at other volcanic locations.”

Everyone encounters situations in their life that determine where they end up. There are forks in the road and “sliding door” moments that alter our paths through life, and for Crisafulli it was a unique and almost supernatural one. One that was also a catastrophe with a tragic outcome.

“It was a defining moment that ended up driving the direction of my life and probably my entire identity. I have to admit, I didn’t realize until I retired just how much of myself was tied up in that volcano,” Crisafulli notes. “But if Mount St. Helens hadn’t erupted, I would have looked for jobs but those are tough to come by in wildlife ecology and I didn’t have a graduate degree. So, in the absence of the 1980 event, the very likely conclusion would have been I just ended up back in New York at the family business.

“I mean, I can’t even comprehend how different my life would have been, and it’s hard to envision a scenario in which I could have had such a fulfilling and enjoyable career. And so, out of this dramatic and tragic event where 57 people died came this great opportunity for me and others. But I’ve never lost sight that it was something that was very painful for many families and individuals.”

Crisafulli’s own family, raised in Utah and Washington, is now spread out. One daughter, Erica, resides in Montana with her husband and two sons (one of which is named Logan, after the place Erica was born), while daughter Teal lives in Vermont. But the 65-year-old still plans to continue living in Yacolt on a six-acre plot of land adorned with a couple of greenhouses, a garden, some orchards, and raspberry and blueberry patches.

And, of course, what he refers to as “The Monument” — the stratovolcano was designated the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument in 1982 — is only about 35 miles away, leaving him with plenty of opportunities to still check in on the “mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, fishes, insects and other invertebrates, fungi, plants of all sorts, and innumerable microbes” that he’s spent two-thirds of his life documenting.

“The volcano is so deeply intertwined in my life that it’s hard to distinguish my identity without including it,” Crisafulli declares. “It’s where we go hiking, fish for salmon and trout, go elk hunting and go cut a Christmas tree each year on Forest Service land.

“I can’t quite see the mountain from my house, but all I have to do is walk or drive 300 feet down the road and there’s St. Helens. It’s forever present.”