Finding Their Place: Preserving Intermountain Indian School Art

Sheila Nadimi M.F.A. ’96 isn’t from Brigham City, Cache Valley, the state of Utah, or even the United States.

Her mother is Iranian, her father is Dutch, and she was raised in Canada. But Nadimi inexplicably developed a deep affinity for a collection of dilapidated buildings in Brigham City and a little-known assortment of artwork housed inside them.

“I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to explain the draw I have to it,” she says of the remnants of the Intermountain Indian School. “Even before I ever stepped foot into it, it just seemed to be fascinating somehow.”

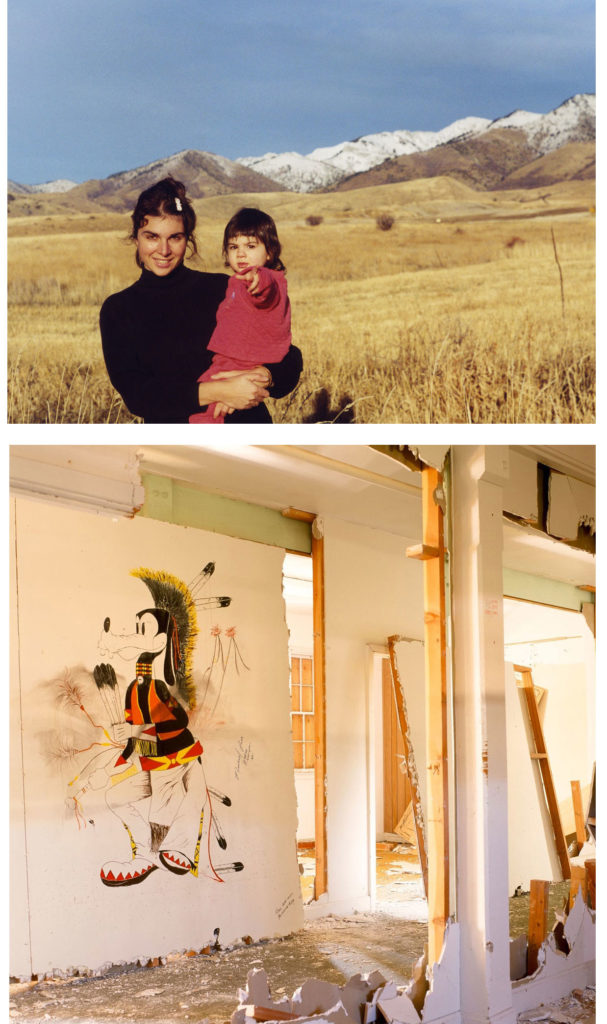

Nadimi first came to Logan and Utah State University (USU) via North Africa. She was working on a master’s in natural resource management in the Sahara Desert when she met and fell in love with Jim Rogers, who was serving in the Peace Corps. Rogers later secured a teaching position at USU, which led to Nadimi relocating to Cache Valley and the couple getting married and having two children. Along the way, she exchanged geography for art and completed an M.F.A. in sculpture at USU. A desire for studio space first led her to visit the site of the Intermountain Indian School.

Originally the Bushnell General Military Hospital, which served soldiers coming back from World War II from 1942 to ’46, was transformed into a boarding school by 1950 with the purpose of teaching and assimilating Navajo children into mainstream American culture. In 1974, it became the largest boarding school in the country, accommodating more than 3,000 Native American students from 100 different tribes.

The school closed in 1984, leaving dozens of large buildings vacant for more than a decade before a developer from New York purchased the property and renamed it Eagle Village – the Eagle referencing Intermountain’s mascot. The plan called to renovate the buildings into a new urbanist community adjacent to Eagle Mountain Golf Course, which was built on the eastern edge of the site in 1989.

While curious about the yellow-brick buildings when driving past on U.S. Hwy. 89-91, it wasn’t until 1996 that Nadimi actually drove into the area. She met a caretaker who told her studio space was out of the question because there was no electricity but showed her inside some of the vacant buildings.

“He had a flashlight, and we didn’t go in very far at all, but I just knew,” Nadimi says. “I needed to come back. I was just fascinated, and I kind of allowed that place to lure me in even further.”

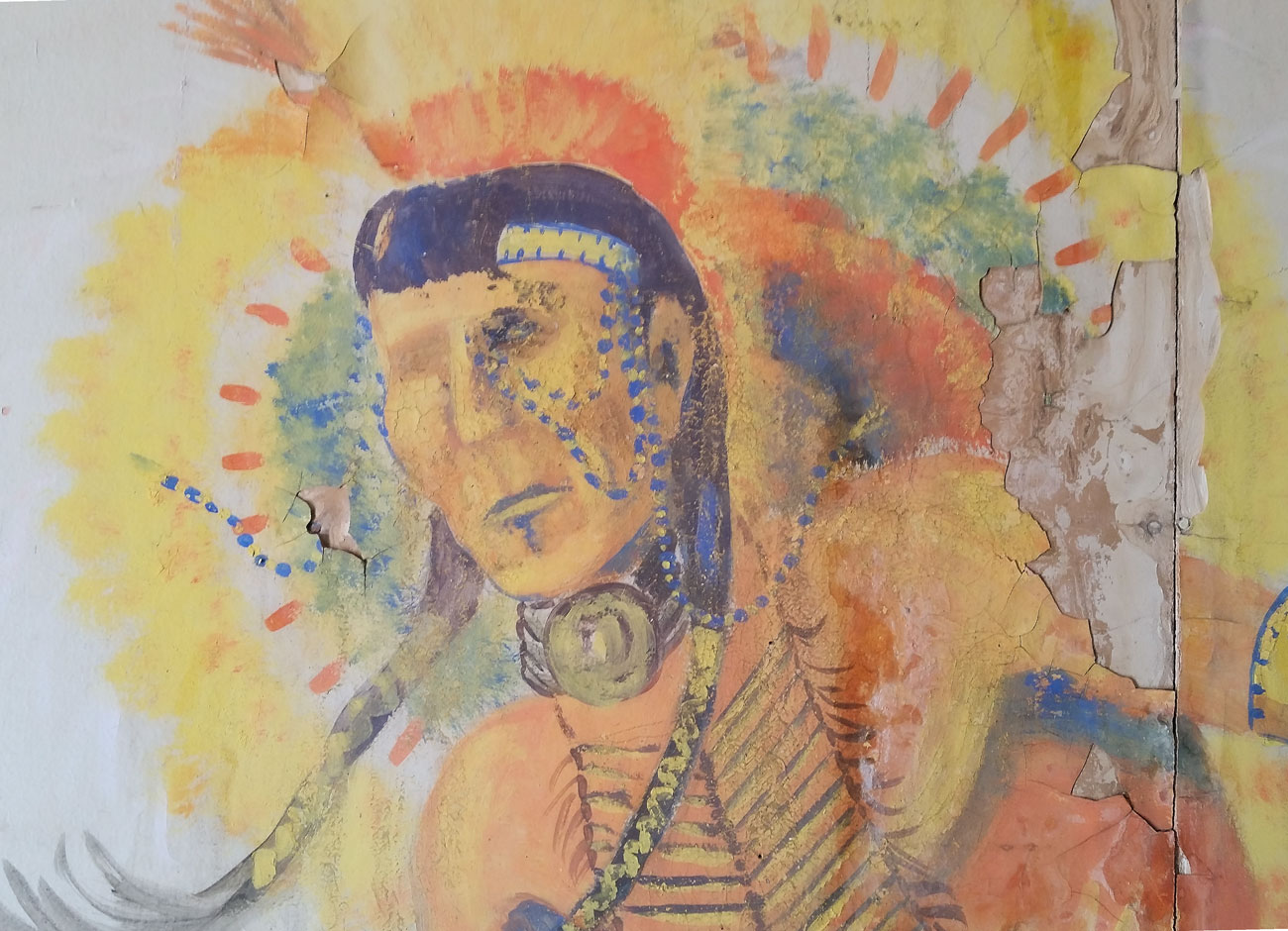

That fascination led to more excursions with the help of the caretaker, where she discovered stunning artwork, much of it created by the students, often on the walls of hallways, or dorm rooms, as well as some more intricate murals. Over time, Nadimi learned that acclaimed Apache painter and sculptor Allan Houser served as the art teacher at Intermountain from 1952 to ’62 and shared his gift in some of the public space areas.

About that same time, a relative died and left Nadimi $5,000. Despite having almost no experience with photography, she purchased a Hasselblad medium-format camera, a lens, and a tripod to chronicle the decaying buildings of the Intermountain Indian School.

Nadimi continued the personal project for years, collecting hundreds of negatives and photographs, not knowing what she would ever do with them. A divorce in 2005 led to her returning to Quebec where she worked as an art professor at John Abbott College, but she never forgot about the Intermountain Indian School.

Caretakers of Art

Eagle Village never materialized as the developers hoped. Just a couple of the buildings became townhomes, a handful were used by local businesses, and the rest sat empty. In December 2010, USU acquired 40 acres of land and 18 structures on the Intermountain Indian School site to construct a statewide campus. Soon afterwards, work began clearing out most of the structures to make room for the current USU building, as well as future campus facilities.

Thomas Lee, director of the USU Brigham City region from 2008 to ’18, says he heard about artwork removed from some of the buildings by the previous owners. Some were on doors or brick walls, while others were on plywood or sheet rock and cut out by a chainsaw and placed in a shed. Others were exposed to the elements outdoors.

The art that could be moved was relocated to the abandoned Kmart building nearby. A prized piece, the painting of a Native American on horseback running across a desert landscaped believed to have been painted by Houser on the wall of the school gymnasium was carefully removed, a steel frame placed around it, covered in plastic, and put in crate. The university brought in an art conservationist to assist as it was painstakingly taken apart in a USU facilities warehouse in Logan.

“There was condensation inside of the plastic, and so as soon as we took it off, the paint started flaking off in front of our eyes,” laments Lee, who retired in 2019. “Unfortunately, it was not able to be preserved. It was quite a day.”

Another mural featuring Monument Valley fared better. It was retouched and now hangs above a stairwell of the USU Brigham City building. But there were other pieces in various states of deterioration in need of a better home, which led to USU bringing in additional resources, including Evelyn Funda, then the director of the Mountain West Center, and Brad Cole, former dean of libraries.

Funda was stunned to find that most of the art had been housed adjacent to chemicals in a lawn-maintenance shed.

“We were like, ‘Oh my God! This is nuts! We have to do something about this,” she says. “As far as I was concerned, we didn’t own them; we just kind of inherited them when we bought the land. So, by default we’re the caretakers of these works of art, and we have a responsibility to do something.”

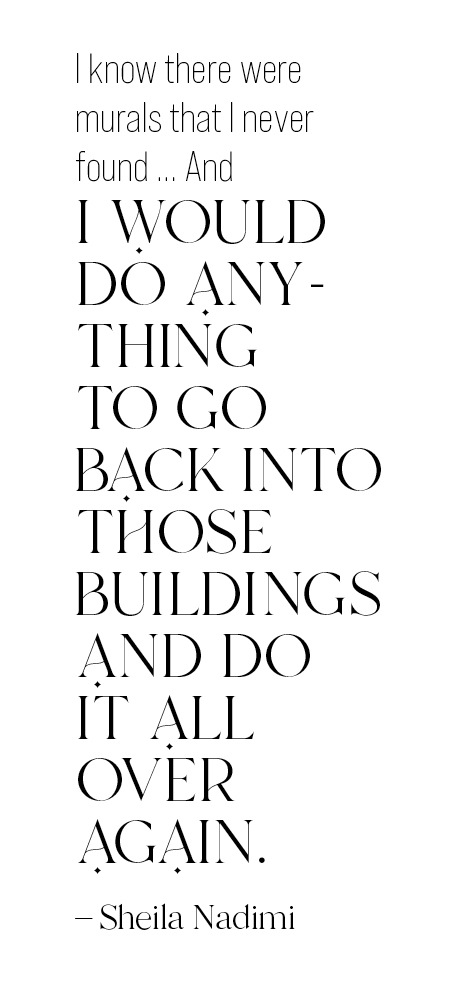

Eventually, 11 pieces were relocated to a temporary storage location on the main USU campus. Two of them were large murals that were in public spaces like the cafeteria, while the rest were likely painted by students on the walls or doors of the dormitories, including a bull elk, a tepee, a Native American dancer, and a horse missing its nose.

“This was art that was part of their everyday lives,” notes Funda, who retired in 2021. “So, it was an exciting thing to work on. But they were all deteriorating, so who knows what’s been lost to time?”

Home Away from Home

Ronald Geronimo grew up in southern Arizona the youngest of nine children. An older brother attended Intermountain, and shortly after going to his graduation, Geronimo asked his mother if he could attend, as well. In 1978 at the age of 15, he took a daylong bus ride to northern Utah, and spent the majority of the next four years in Brigham City.

“I enjoyed it,” he says of his time at Intermountain. “It was home away from home.”

Geronimo would have graduated from the boarding school in 1981, but failed English. He returned home to the Tohono O’odham Nation assuming he would never get a diploma, but he got a call saying that he could return mid-school year if he could get back to Intermountain by the next day.

After another long bus ride, Geronimo resumed his studies, and he credits his English teacher for helping get him where he is today, co-directing the O’odham Language Center at Tohono O’odham Community College in Sells, Arizona.

“After I got my bachelor’s, I called Mrs. (Evelyn) Pohmajevich and thanked her for not letting me graduate,” explains Geronimo, who completed a bachelor’s in education and a master’s in linguistics at the University of Arizona. “She made me earn it.”

Geronimo has attended several reunions of former Intermountain students through the years. It was while at one that he saw a picture by Logan-based photographer Brad Peterson of a painting in a dormitory just before it was torn down. The self-portrait created by Geronimo’s friend Nolan Lopez, includes the date of 1981 and the term “Papago,” the name for the Tohono O’odham people of the Sonoran Desert used by early Spanish colonizers.

Geronimo had Peterson’s photo of the painting reprinted on canvas and surprised Lopez with the large image more than three decades after it was created.

“He was surprised and happy when I gave it to him,” Geronimo says. “He remembered drawing it.”

Geronimo fondly recalls some of the other artwork created by Intermountain students in the dorms, as well as the larger murals in public spaces like the cafeteria and the theater.

“The school had more than 100 different Native American groups there, and me coming from southern Arizona, I was really only familiar with the Navajo, the Hopi, and the Apache,” Geronimo notes. “But when I got there, there were so many other Native American groups that I wasn’t really familiar with, and each had their own language, their own traditions, customs, songs. And a lot of times you want to show own culture and your own language, things like that, and I think the artwork there reflected that.”

Representations of Themselves

For his master’s thesis, USU graduate student Carlos Guadarrama, ’16, M.S. ’18, who grew up in Brigham City, wrote about the artwork at Intermountain. The thesis, entitled An Analysis of Murals Painted by Students at Intermountain Indian School in Brigham City, Utah, includes an interview with former Intermountain art teacher Peggy Barker, who came well after Allan Houser but felt the renowned artist’s work played a significant role at the school many years later.

“These paintings were incredibly empowering for the students as it showed students — for possibly the first time in their entire lives — that their culture was important enough to be placed on a public wall,” Barker told Guadarrama. “I believe that Houser’s paintings worked with the school’s art curriculum guidelines to encourage students to paint their own representations of themselves on their dormitory walls. Because most of the murals that were painted came after Houser left Intermountain, the students used what they saw in the gym and theater to paint the murals in their dorms.”

A statement like that re-emphasizes the significance of salvaging some of that artwork, mostly notably the 11 pieces now in USU’s possession. Katie Lee Koven, executive director and chief curator of the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, had the Intermountain art placed in a climate-controlled storage facility and formed a committee to help decide what should be done with it all. She had the pieces evaluated and received an estimate of $90,000 for treatments and framing, the majority of which she expects to be covered by a grant.

Once the paintings are restored, Koven plans to host an exhibit at NEHMA, augmented by Nadimi’s photographs, which is scheduled to open in January 2024. After the exhibit closes, the artwork will be returned to Box Elder County where it will be placed permanently in the USU Brigham City building not far from where it was originally created. The hope is to continue the legacy of pride in one’s culture and native land that Allan Houser helped foster 70 years ago.

His teaching was instrumental to the creative expression of students who painted and drew the stories, imagery, and symbolism of their tribes, Koven explains. “It’s not just that they were given pieces of the paper. It was on the walls; it was in their dorm rooms; it was in private spaces that were just for them.”

Eagle Village Encounters

in the climate controlled storage unit. Photo by Levi Sim.

More than 25 years after spending hours taking long-exposure images in the dark halls and rooms of the Intermountain Indian School, Sheila Nadimi finally knows what she’s going to do with all of the photographs she took: she’s compiling them into a book.

Entitled Eagle Village: A Deep Mapping of Fallow Architecture, the book is slated to be published this fall and tells the story of the Intermountain Indian School and Bushnell Hospital. During the fall of 2021, Nadimi returned to Utah on sabbatical, working with BYU historian James Swensen, who co-authored a book Returning Home: Diné Creative Works from the Intermountain Indian School with Farina King, a Navajo professor Oklahoma who is also a member of Koven’s Intermountain artwork committee.

Nadimi walked the vacant grounds of the Intermountain Indian School and came to realize that it was a place of transformation.

“You were supposed to arrive in one condition and leave in another,” she says. First, the wounded soldiers coming back from war needed to regain their health in order to return to society, and then young Native Americans, “brought there hopefully to give them the skills and the vocations, the world views, and the aspirations to kind of buy into the American dream.”

Because of recent events in Canada, as well as the United States, where it’s been unveiled that Indigenous children sent to residential schools often suffered physical abuse in an effort to impose “cultural genocide,” Nadimi struggled with her book project amidst the complicated legacy of government supported Indian schools.

In May, the U.S. Department of the Interior released an investigative report into the events and outcomes, including generational trauma and family separation, of federally run (and funded) Indian boarding school policies. The analysis found that between 1819 and 1969 there were over 400 federal schools across 37 states or territories, including 7 in Utah, and, alarmingly, more than 500 American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian student deaths at them. The interior department will continue to address “the last legacies of these policies,” Interior Secretary Deb Haagland said about the investigation.

For Nadimi, after learning more about Intermountain through conversations with alumni at reunions, she realized that many students had positive experiences there — at least those who attended later in the school’s history when expressions of Native American culture, such as artwork, were no longer discouraged. After those conversations she felt more compelled to try and capture the history of that little, 250-acre plot of land” primarily through photographs.

“Now I’m proud of my photo archive, and I’m proud of the book,” she says, “And I hope other people will be happy that place can live on now through these images.

“I know there were murals that I never found,” Nadimi adds somberly. “And I would do anything to go back into those buildings and do it all over again.”

Jory 38 October 28, 2022

my father mentioned the drawings in the buildings be nice to see more if possible.

Laura Christensen September 7, 2022

Help preserve these powerful images and share them with the world. Join in to bring Sheila Nadimi’s book of photos to life: https://gofund.me/92638780

Alvin Reiner September 5, 2022

I am not sure if you want this for your Bringing War Stories Home. If so Google “Alvin Reiner Remembering Vietnam”.

Alvin Reiner, College of Natural Resources Class of Dec. 1972.