Finding Her Freedom

One legend about Joshua trees is that their upright limbs beckoned Mormon pioneers westward to a promised land.

With their spiky tops and rugged bark, Joshua trees, a yucca plant, are hard to know. Their age cannot be determined by counting tree rings and their survival is dependent on a rain that rarely comes. But Joshua trees endure in one of the least hospitable environments in North America.

Genéa Gaudet, ’97, does, too. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the self-described “introvert” and “city girl in every way” exiled herself to the Mojave Desert from downtown Los Angeles to “build an art life … to work on the projects I want to be working on. I am a creative. I want to create. I am tired of waiting for other people to fund it.”

Not having to pitch herself or her work at LA networking events during the pandemic has been a quiet blessing.

“Because I am not missing out, I recognize how much this is good for my soul and has allowed a lot of healing,” she says.

For two decades the Canadian American filmmaker stitched together a successful career filming videos for musicians the likes of Andrew Bird, editing hundreds of commercials, and hustling to fund her own feature-length films and short documentaries. Her acclaimed short Elder premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2015. “Tom’s story captivated me not only for its poignancy, but also for its universality: It captures the moment love emboldens you to become who you truly are, and explores the powerful hold religion, family and culture have on shaping our individuality,” she wrote of her subject in the New York Times.

That same year, Jesustown, USA, a film she produced and edited, which followed a young man questioning his faith in one of the holiest sites in America, was picked up by Showtime. Gaudet’s latest credits include Pride, a six-part series chronicling the history of the LGBTQIA+ movement in the United States that appeared on Hulu in May.

Her filmography often tells the stories of outsiders. People estranged from their religion or relationships. Gaudet doesn’t seek out stories of people living on the edges of their communities, but when she reflects on the observation, she notes, “I think I can relate.”

A city of 4 million people, five acres of remote desert dwelling, both are places where it’s easy for a person to disappear. Gaudet didn’t want to disappear. She wanted solitude. No distractions. No networking meetings, just a network of dirt roads and an endless horizon.

“All there is is abandoned spaces,” she says over Zoom. “I have a thing about abandoned spaces.”

That much is evident in her photography. Her Instagram feed is a love letter to the high desert and its decaying homesteads. Gaudet is from the Canadian prairie near Winnipeg. She moved to the high desert to take a creative breath.

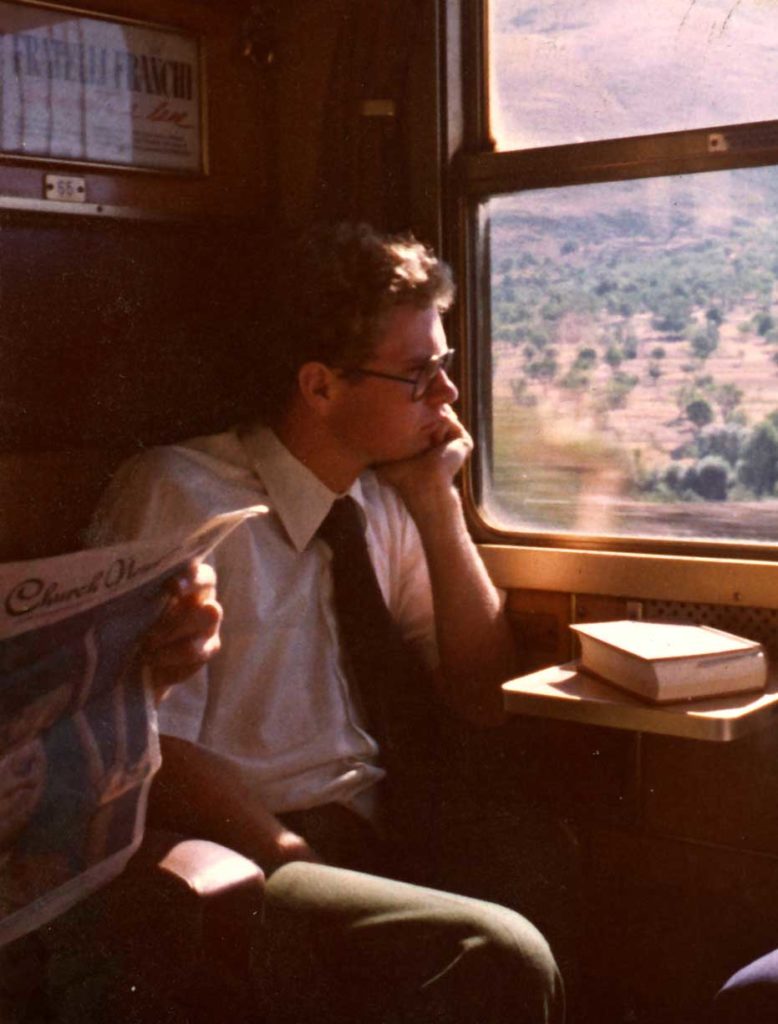

Before majoring in journalism at USU, she was a creative writing major attending college in Vancouver, Canada. She met a missionary from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and moved to Utah without ever locating the state on a map beforehand. She found her way to Logan where she majored in journalism because that was the only writing program she could find. Gaudet got married, found her footing reporting for the Statesman, and by senior year, she was its editor and pregnant. She graduated in 1996, a new mother to an infant daughter.

Afterward she turned down a job with the Associated Press to stay home with her daughter for two years.

“Knowing me now and how career focused I am, I can’t believe I did that,” Gaudet laughs. “But it was a blessing for her for me. I’m so glad I did that.”

She got divorced and went to film school at the University of Utah. But the journalism program at USU left an impression — a powerful one. There were several strong, professional women on the faculty, Gaudet recalls. “I think it was important for me to see those role models.”

She felt supported by teachers like retired department head Ted Pease and Jay Wamsley, who oversaw the Statesman, people who taught her how to develop a story and provided her with the ethical grounding she still abides.

“These principles that I still work with on a daily basis — those high standards,” Gaudet says. “I feel like journalists take an oath, like doctors, to ‘do no harm.’”

“I am very unbiased when I approach my subjects,” Gaudet says. “I am just super interested in exploring humanity. I don’t think you need to lead an audience. People aren’t stupid. And they do sense when you have an axe to grind.”

Gaudet aims to tell good stories without judgement. A project she is polishing has stretched five years and wrestles with the complexity of the justice system and child sex abuse. Her feature length documentary Five Days recounts the days leading up to the trial of a father accused of sexually abusing his daughter. It can be hard material to sit with. But Gaudet’s goal is not to prove his innocence or guilt, but to tell his side of a dark story.

In March, she was in the final stages of editing Pride, a project that was a labor of learning. She had never worked on a historical project before and wasn’t fully versed in the history of the American LGBTQIA+ movement.

“I think people will be shocked to hear about some of the laws that were in place and how deep the discrimination was,” she says. “The laws that were the most shocking to me were the [transgender] laws. They would get arrested for jaywalking or littering. But they were really getting arrested for being trans.”

Soon the 46-year-old filmmaker will put her camera down to focus on fiction — to become the writer she always intended to be. Moving to a place stripped of human excess, surrounded by life managing to hold on, is the ideal place to transform. Gaudet is less focused on the what, but the how she creates. Maybe it will be experimental installations. Maybe films. Maybe fiction, she says. But it will be entirely from her.

“Whatever comes out of that is what I want to do.”

By Kristen Munson

Learn more about Genéa’s work or follow her on Instagram.

Frank D Mathis August 5, 2021

All lives matter. The statement Black Lives Matter automatically creates division. I have nothing against black people but I believe all lives matter., We are all Americans no matter if you are Black White Yellow or Red. ALL LIVES MATTER