Bringing War Stories Home

The artifacts of war often reflect the everyday aspects of it.

Birth certificates from babies born on overseas military bases. Art etched onto artillery shells out of sheer boredom. Knickknacks carried for luck or something like it. Draft orders of a soldier who never came home. Two Utah State University scholars are collecting the stories attached to the objects we keep stashed in closets and displayed on mantels as one way to understand the history of war.

For Susan Grayzel, a history professor co-directing the two-year Bringing War Home: Object Stories, Memory, and Modern War project, one item is her grandmother’s civil defense volunteer pin, a relic of the training she underwent in World War II while living as a wife and mother in Brooklyn. Most of the time the pin sits in Grayzel’s jewelry box. Sometimes she fastens it to her lapel before lectures.

“What our project is trying to do is capture the personal history associated with objects,” she explains. “Someone is living with this piece of history that tells a family story but also contains part of all of our history. We want to preserve these objects and histories so they don’t get lost.”

(LEFT) RONALD RED-ELK ATEWUTHTAKEWA, a historian of the Comanche tribe, from the April roadshow for the Bringing War Home project at Hill Air Force Base. (RIGHT) Flags from the Comanche Nation. (BOTTOM) A German WWII helmet.

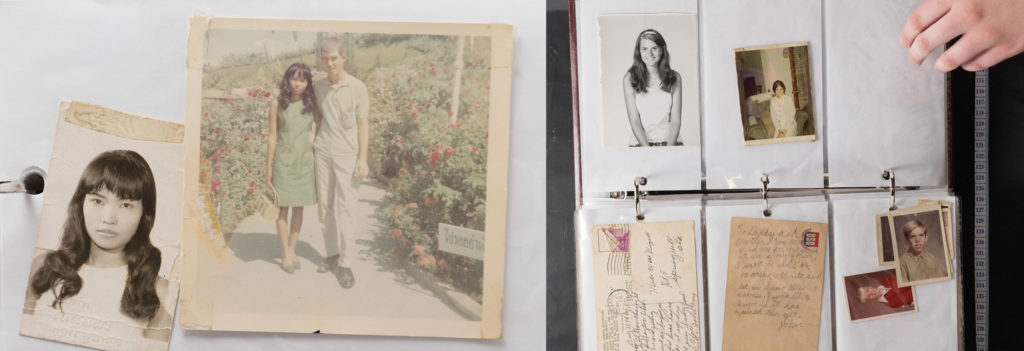

(LEFT) PHOTOS are among the everyday artifacts that show the human side of war. (RIGHT) Letters from service officers questions about home such as “I would like to know if it has rained ther (sic) yet.”

In 2021, the National Endowment for the Humanities Dialogues on the Experience of War program funded Bringing War Home to help document ordinary objects and stories of war to capture the diverse experiences of veterans, military families, and civilians. While the project emphasizes stories about material culture from World War I and the Vietnam War, artifacts from all conflicts involving the U.S. military will be preserved in a digital archive housed at the USU Libraries.

As part of the project, co-directors Grayzel and Molly Boeka Cannon, an anthropologist who heads USU’s Museum of Anthropology, jointly taught a class on the history and material culture of modern war to involve students in the process of recording objects and stories. Boeka Cannon is well versed in using objects to share stories. She is less familiar in collecting war histories.

“I am pretty much a student in this class along with the undergraduates learning the history of each of these wars,” she confesses. “What I really like about this project is we are building a public history. It’s your history, and it’s my story, and it’s where those come together.”

At its core, the project centers on community participation. Grayzel and Boeka Cannon have held several roadshows around the state for people to share their stories about artifacts of war. They are also teaching the next generation how to document these experiences. Senior Becca Crummitt, a history major from Preston, Idaho, is no stranger to preserving narratives. She is Native American and grew up listening to relatives talk of their history and the need to share it.

“We are from the Comanche Nation and the Comanche Nation are warriors,” she says. “Many of my family members were in the military and in World War II when there were Comanche code talkers. … I’ve always been interested in learning about that part of my culture.”

In April, as part of her Museum Studies class she signed up to record stories for the event at Hill Air Force Base. She realized her great uncle Ronald Red-Elk Atewuthtakewa, a historian of the tribe, would be passing through the area from Oklahoma. She floated the idea of him sharing the story of his brother Roderick Atetewuthtakewa Red Elk, who served as a Comanche Code Talker deployed to the European Theater during World War II.

“He [Ronald] is one of the people who actually helped create the written version of the Comanche language,” Crummitt explains. “Some of his siblings were the ones in WWII who were the Comanche code talkers. … He is like the one person still alive who can give that information.”

Witnessing people describe the items they came to share underscored for Crummitt how important it is to stop and listen.

“There were so many older people who were in the military who didn’t really get the chance to share their story and share how their lives have been affected and how they have affected others’ lives,” she explains.

And it’s important to listen to stories you think you’ve heard before. Crummitt’s uncle shared how sometimes war isn’t a series of battles.

“He was talking about how there was a war on his language,” she says. “When [I] do think about war, I just think about World War II. … There are so many other definitions of the war that people don’t think of. And I think that is really interesting that he brought that up — that war isn’t always just like a battle between people, it can be against objects or things.”

By Kristen Munson

Photos by Levi Sim

Details can be found on the Bringing War Home website.

Utah Public Radio is partnering with the Bringing War Home project and will record stories from veterans and their families at upcoming roadshows. Learn more about how to get involved.

UPCOMING ROADSHOWS

September 17, 2022 • USU Salt Lake Center

October 22, 2022 • USU Moab Center

November 5, 2022 • Historic Wendover Airfield Museum