A Living Legacy

One frigid October morning, tiny snowflakes whirl past the Manon Caine Russell Kathryn Caine Wanlass Performance Hall. The snow disappears the geometric pattern segmenting the cement walkway between the hall and the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art. The powder seems to absorb all the sounds of morning. There is no birdsong. Even footsteps are silent. The unexpected storm forces a kind of quiet reflection.

Ann Preston, the artist responsible for “Passacaglia,” the behemoth sculpture of repeating gray and silver tetrahedral shapes adorning the lobby of the performance hall, once described the building as having “a vulnerability, an openness” that allows one to “think your own thoughts and feel your own feelings.”

She could have been describing the hall’s namesakes. Their portraits hang beside the sculpture, which Preston crafted to invoke “passacaglia,” a musical composition of successive variations over a steadying base. Similar but independent. Different but melodious—like the women of the Eccles and Caine families who shaped the landscape of the arts at Utah State University for the last half-century.

Ross Peterson, ’65, USU emeritus history professor, recalls meeting Marie Eccles Caine, “the catalyst” for the family’s philanthropy to USU, while an undergraduate studying history. She was passionate about the arts and endlessly curious. She came to everything from visiting speaker series to musical productions, Peterson says. “She was a presence. It wasn’t like a grand entrance—she was just there.”

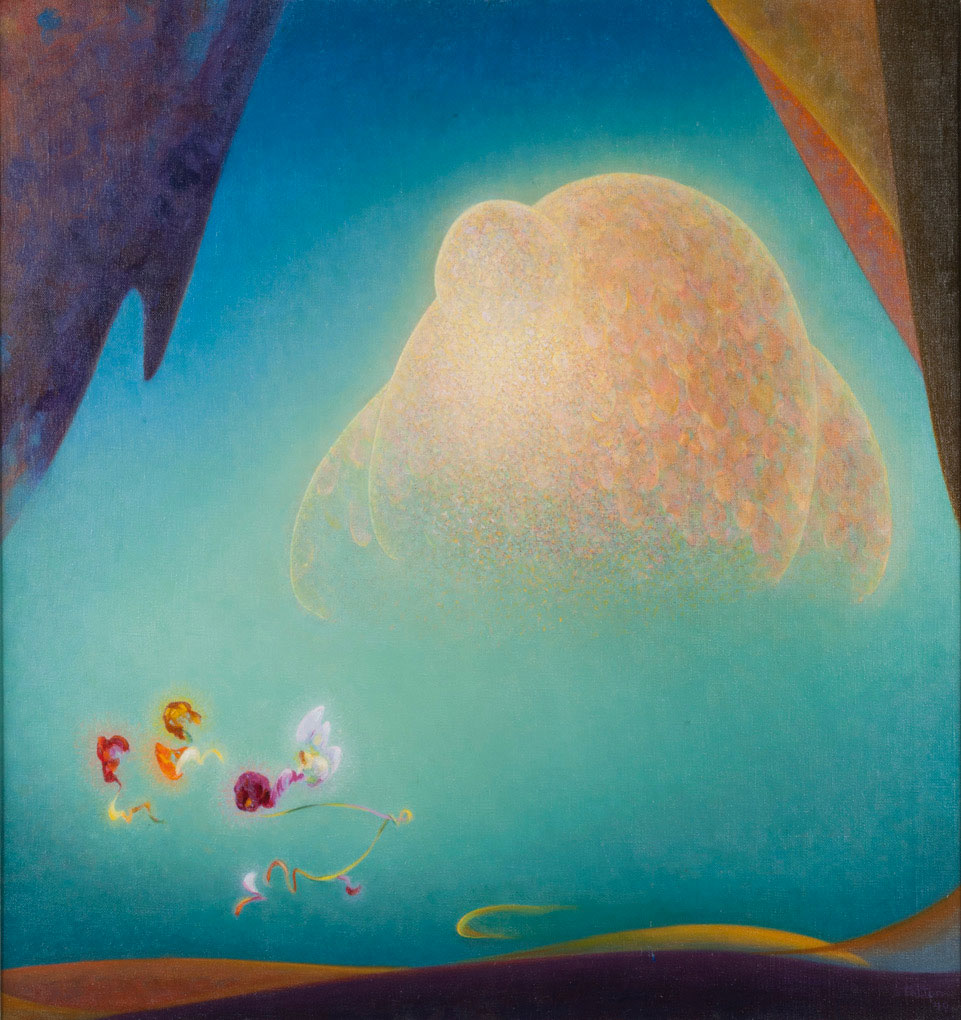

Agnes Pelton, “Nurture”, 1940, oil on canv as, 34.375 x 32.5 inches.

Gift of the Marie Eccles Caine F oundation. Collection of the Nor a

Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Ut ah State University.

Marie was the type of person who penned handwritten notes of encouragement to students, Peterson says. He knows because he received one. Her support of students was unflagging and something she passed down to all three of her children: Kathryn ’38, George ’43, and Manon ’53. Marie cultivated a living legacy through her family’s giving to the arts with the establishment of scholarships, visiting artist series, permanent collections, library resources, and world-class facilities. She wanted to “create an atmosphere of culture, of art, and art appreciation so students could not only develop their own talents but appreciate them in others,” Peterson says.

Without this mindset, and a desire to do things that benefit the whole community, the concentration of arts programming and facilities would not be here at Utah State, he says. “It was never about them. They did it because they cared and they cared about this place.”

Marie Eccles Caine was born into a pioneer family in 1892. Her father, David Eccles, was an enterprising Scottish immigrant who moved to Utah as a teenager and built a fortune from lumber, railroads, and banking endeavors, among others.

“It was never about them. They did it because they cared and they cared about this place.”

“Grandmother’s dad came from nothing,” says Marie Russell-Shaw from her home in Montana. “Maybe knowing the difference between having very little and being able to give to others who have less than you,” helped spark their giving, she muses.

In Scotland, his family had to work so hard to stay alive, she says. “I think he was just amazed by the opportunities he was given to prosper here, and he wanted to share those opportunities with others.” If you care about something, Russell-Shaw says, share that with other people. “Grandmother always felt like art and music just made the world a better place.”

Marie and her eight siblings were raised in Logan and she attended the Agricultural College of Utah (UAC), now USU, where her husband George Ballif Caine founded the dairy sciences department and served as department head for nearly 40 years. They raised three children at the base of Old Main Hill and each attended USU. But before motherhood, before she married, Marie painted.

She moved east to study at the Chicago Art Institute and in New York. It was very unusual for a young woman to do that at the time, Russell-Shaw says. “She strongly believed in women’s rights to be independent and to have equal opportunities. She had opinions and felt that women of all kinds, in all fields, should be respected for what they were capable of doing. That was definitely a part of her philosophy.”

Marie Eccles Caine nurtured a culture of giving to the arts by her family members that continues today.

Marie was about 5 feet tall—if that—and a person who, in her eighties, decided to learn how to drive. (“Oh, it wasn’t good,” Russell-Shaw confides.) Marie earned a restricted license to cruise about town, and when she wanted to visit friends and attend the symphony in Salt Lake City, she boarded a bus in Logan wearing a wool coat with a fur collar.

Marie was not afraid to share her opinions or passions with people. Neither was Russell-Shaw’s mother Manon. “My mom was very willing to let you know what she thought,” she says. Manon loved the outdoors and was heavily involved with the Girl Scouts. And like her mother, Manon had a love affair with the arts. She studied music and sang in choirs and operas—a natural fit considering she was named after an opera.

Manon Caine Russell’s gifts continue to support students and the performing arts at USU.

“My grandmother exposed mom to the arts at an early age, which sent her on a lifelong path of enjoying all sorts of music and also the visual arts,” Russell-Shaw says.

She was named after her grandmother. “Which characteristics of my grandmother was [my mother] thinking of when she named me?,” chuckles Russell-Shaw. Marie’s love of nature and music is something she recognizes in herself.

“Growing up my grandmother stayed with us often, and every Saturday afternoon she’d turn on the opera,” Russell-Shaw remembers. She would listen too, for a spell. “I was pretty young and opera does go on a really long time. But I think when you see someone appreciate something so much it did inspire curiosity later in life, and I do enjoy it now. She definitely brought your attention to look at things in a way that wouldn’t have been my natural instinct.”

Marie would notice things others didn’t always see.

George Wanlass has similar memories of his grandmother. He credits her with instilling in him a willingness to look at the beauty of the world.

“She thought Logan Canyon was one of the beauty spots of the world,” he says. “I remember driving up Logan Canyon with my grandfather and grandmother and she was sort of like a lecturer. She would tell you where to look, and her excitement and the wonder that she conveyed was contagious. I guess I had a natural inclination to want to look at those things too.”

Whenever Wanlass visited his grandparents he noted the Henry Moser painting hanging over the piano. It was this noticing that drove him to ignore a shoddy frame around a treasure in a junk shop in Hyrum.

“The very first thing I ever bought was a very small painting of Bear Lake by Henry Moser,” he says. “I remember paying $7.50 for it.”

The acquisition launched Wanlass on a path of art collecting that began with Utah artists in the 1890s–1930s and led to works by under-appreciated artists of the American West. It’s a passion he has continued for the last 30 years. And USU has benefited from that passion.

“The very first thing I ever bought was a very small painting of Bear Lake by Henry Moser. I remember paying $7.50 for it.”

The art collection at the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art (NEHMA) has more than 5,000 objects—more than 1,000 of which were gifted by Wanlass through the Marie Eccles Caine and Katherine C. Wanlass Foundations. The museum was established in 1982 by Nora Eccles Harrison—Marie’s sister and Wanlass’ great aunt—with an initial gift of $2 million and 400 ceramics from her personal collection. Wanlass has helped to build and shape the collection since the museum’s founding.

“He has been the largest influence in terms of the uniqueness of the collection,” says NEHMA director and chief curator Katie Lee-Koven.

Wanlass is trained as a historian and spends hours scouring auctions—big and obscure—hunting for exceptional pieces by under-recognized artists. This is unpaid work he does on behalf of the museum. And his research has paid off as Wanlass has routinely been “ahead of the market,” purchasing pivotal works just before artists get recognized, Lee-Koven says.

“We’ve never collected based on the market value; it’s never been about that. It’s about expanding the stories of art in the American West.”

Strolling through NEHMA, one may notice works by more female artists than typically found on the walls of many metropolitan museums.

“There are two reasons for that,” Wanlass says. “One is because I believe in equality. But beyond that, there are some very talented women artists in the American West who are under recognized. For instance, an artist named Agnes Pelton is just starting to get some attention. But way back when I bought something for the museum a lot of people didn’t know who she was.”

Wanlass is like his great aunt in that regard.

“She was very prescient in certain fields,” he says, noting her eye for jewelry design. Nora’s first husband was the photographer Walter Treadwell who trained with Ansel Adams. (NEHMA has a folio of Adams’ in its collection.) But ceramics interested her most. She was a potter intrigued by Southwestern ceramists. Among NEHMA’s collection is a documentary film on Maria Martinez, that Nora produced.

“I didn’t have a lot of exposure to Noni,” Wanlass admits,“but I remember how charming she was and how interested she could be in a young person.”

She could make someone feel that what they were doing and creating was important. Wanlass points to a drawing he made as a kid that Nora made into a tile, “which bestowed an importance on it that I don’t think it had originally.” Wanlass still has that tile in his kitchen.

Nora “Noni” Eccles Treadwell Harrison is the namesake for the university’s art museum.

Nora’s ability to make young persons feel valued continues to be part of the educational programming at NEHMA.

“We realize that many students at USU may never have stepped foot in a museum before,” Lee-Koven says, adding that NEHMA strives to be an accessible resource for the community. It has a mobile art truck that brings art education to schools and events off campus. The museum doesn’t charge admission either, making K-12 students a regular sight at exhibitions.

Perhaps early exposure to the arts can light a fire within. At least, that’s what happened with Wanlass. At 16, his mother Kathryn “dragged” him to some of the great museums of Europe. “It made a lasting impression,” he says.

Like her mother, Kathryn had an exceptional eye for color and a sense of responsibility to one’s community. “When we grow up in a family, we don’t realize until subsequently after, how beautiful our parents are, especially our mothers,” Wanlass says. “She was concerned about other people.” When she moved back to Logan she joined boards including the Sunshine Terrace and Ellen Eccles Theater because she wanted to contribute to the community, not just monetarily, but with whatever expertise that she had, he says.

Kathryn C. Wanlass gave her time and talent to improve the art scene in Cache Valley.

Marie Eccles Caine instigated a culture of philanthropy and service to a region outside the rail lines that helped generate the family fortune. Collectively, her family members have given more than $16 million to the arts at USU. When the performance hall was built, her daughters secured a world-class architectural firm that could marry the buildings already in place with a new point of view.

The Manon Caine Russell Kathryn Caine Wanlass Performance Hall is like no other building on the Logan campus—an exterior that is both austere and complicated, with a welcoming interior that nurtures the best from performers alike. If Marie could see what she sparked decades ago, both Wanlass and Russell-Shaw believe she would be most proud of the performance hall. The funding for it was provided by her two daughters, and the acoustics and the beauty of it are inspiring, he says. Marie would have loved to attend a performance there.

As a child, Megan Wanlass spent a lot of time in the vestibule of her great-grandmother’s home waiting to take her to USU events. It was a legacy that continued with her grandmother and she credits her family’s support of the arts as what steered her toward a career in theater—a journey that began with Unicorn Theater in Logan. Children’s theater still exists in Logan today, in part, because of Marie’s initial gift.

Both Megan and her father believe that children’s theater can be transforming for kids and set the stage for a life-long appreciation of the arts.

“Something communal happens in theater,” she says. “People all come together, which is very rare in the world these days. They witness a model society or a society that is challenged by something. I think it’s a great way to have difficult conversations.”

Megan’s daughter recently turned 16 and has spent much of her childhood attending productions with her mom. It may, hopefully, leave a mark.

“We are definitely a family that has inherited this love of the arts,” Megan says. “And it goes on generations now.”

By Kristen Munson