Breaking Through

A century ago, Mignon Barker Richmond, the daughter of an English woman and an escaped slave who served as a drummer for the Union Army in the Civil War, became the first African American to graduate from college in Utah.

While attending Utah Agricultural College, now Utah State University, Richmond endured racist faculty members and graduated only to find her degree did not unlock any professional doors. It would be another three decades before Richmond found professional employment and before the next cohort of African American students arrived at Utah State. And it wasn’t always easy for them either. As Utah State charts a path that puts inclusion of all students at the center, it must first reckon with the past.

Editor’s note: This story describes historical incidents of racism and contains slurs when quoting for accuracy. Language may be offensive to some readers. The individuals interviewed in this story identify as African American, however, the broader term Black will be used when preferred identity is unknown. Black students, educators, coaches, and administrators at USU are in bold type throughout the article.

A WOUND THAT WON’T HEAL

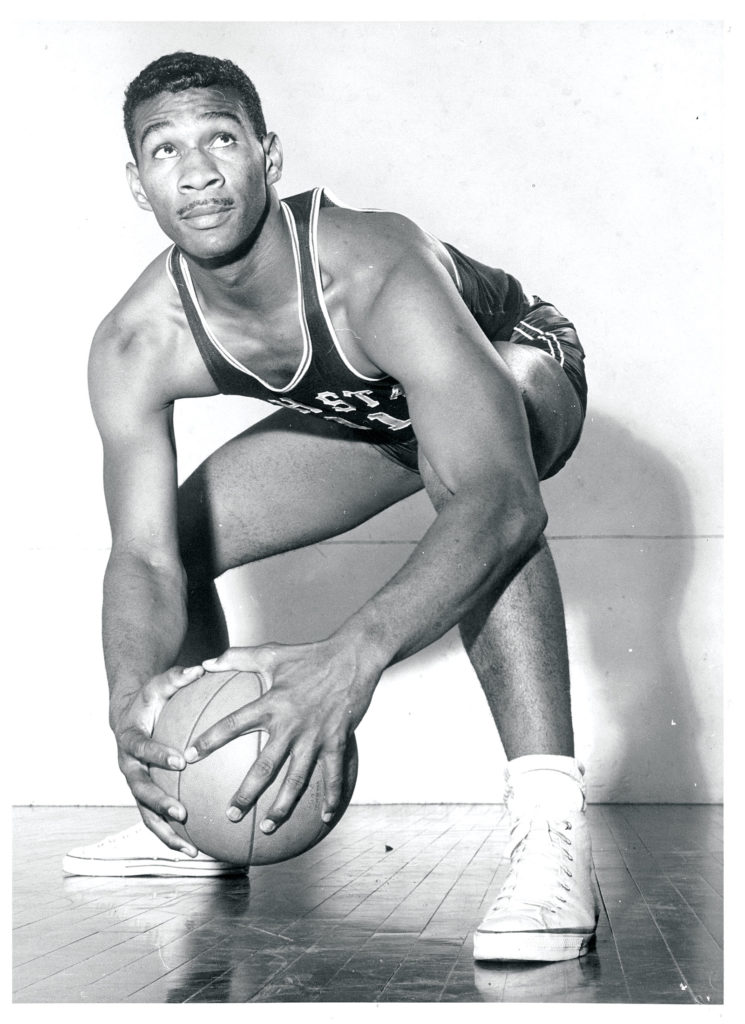

The 1954 Buzzer yearbook features head shots of 535 freshmen students at what was then the Utah Agricultural College (UAC). Only one is African American—Maceyo Vaughan.

His photo is four times the size of the rest. It seems it needs to be larger to accommodate the Springfield, Massachusetts native’s delightful smile.

“My bride has always said I have a beautiful smile,” Vaughan proudly notes.

Unlike his fellow freshmen on page 135, Vaughan’s name, incorrectly spelled, is in a stylized font in significantly bigger type.

“Friendly to all Aggies,” the text reads. “Played freshman basketball. Imitates Billy Eckstein’s singing. Known as Mayce.”

Never mind that Vaughan’s nickname “Mace” is also spelled wrong. But despite being one of just five African American students on the Logan campus, Vaughan found a happy home there.

“I had so many friends there, and I do mean genuine friends who made me feel like I was a native of Utah,” he says, now 87 years old and living in Georgia.

Vaughan came west at the urging of Barre Toelken ’57, a high school classmate studying natural resources at UAC.

“Barre told me, ‘Mace, come out. It’s great.’ So, I came on out,” Vaughan says.

Toelken, who later became a much beloved folklore professor at USU, suggested that the star guard on his high school team try out for freshman basketball. Vaughan made plans to come for a tryout.

“I believed in myself enough to take the chance that I could earn a scholarship, because if I hadn’t made the team, I would have had to go right back home,” he says.

Vaughan made the team for the 1953-54 season, and the photograph in the Buzzer shows him sporting that big smile, the only African American out of 10 players on the squad.

When asked how his team fared that year, Vaughan doesn’t hesitate: “All that mattered was we beat BYU!” he proclaims with a big laugh, adding that he converted the winning basket just before the game ended.

“It was a jumper from the top of the key at the buzzer, and as soon as it went in, I was mobbed on the floor with everyone on top of me,” Vaughan recalls.

But that would be as good as it got for Vaughan in collegiate basketball.

After returning in the fall of 1954, he was devastated to find that his scholarship was “scuttled.”

“I was told by another player that I had made the team, but that one of the more established varsity players told the coach [H. Cecil Baker ’25] that if I played, he wasn’t going to play,” Vaughan says quietly. “Apparently he didn’t like Black folks.”

“I don’t know for sure if that’s true,” Vaughan continues. “So, I didn’t get a scholarship my second year, and I was badly hurt by that because I couldn’t afford to go to college without that scholarship. That’s a wound that will never heal.”

Maceyo Vaughan may have been the first African American athlete to play basketball at Utah State.

USU Athletics Department records are incomplete, but as Vaughan remembers it, there were only four other African Americans — all men— on campus in 1954: a graduate student in the forestry department, someone who played a little bit of football, and Aaron Dixson ’57 and Ezra “Zeke” Smith ’57 both players on the varsity Aggie football team.

“As far as I know, we were the only Black people at Utah State then,” Vaughan says.

He came to USU just a few months before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board of Education, a landmark decision that ended racial segregation in public schools.

At the time, there weren’t many African Americans in the state — less than .5 percent of the population — but that doesn’t mean racism was absent. It also meant it was more difficult to organize to effect change.

In 1953, the year Vaughan enrolled at Utah State, the Utah legislature clarified its miscegenation law, further maintaining its prohibition on interracial marriage and was among the last states outside the South to repeal it.

Jessica Nelson M.S. ’17 explored racism in Utah, and at Utah State, for her thesis “The Mississippi of West”: Religion, Conservatism, and Racial Politics in Utah, 1960–1978,” which won the Lester E. Bush Best Thesis Award by the Mormon History Association in 2018. She suggests that Black Utahns experienced “a distinctly oppressive environment.”

“Jim Crow segregation in Utah only sometimes reared its ugly head overtly; racially discriminatory practices in housing, public accommodations, and employment were rarely formally pronounced, and yet powerfully shaped black life in Utah,” she wrote.

PROTECTING ONE ANOTHER

For African Americans who attended Utah State in the late ‘60s, racism didn’t usually come in a physical form. But there was a feeling that invisible boundaries were drawn, and they should not be crossed.

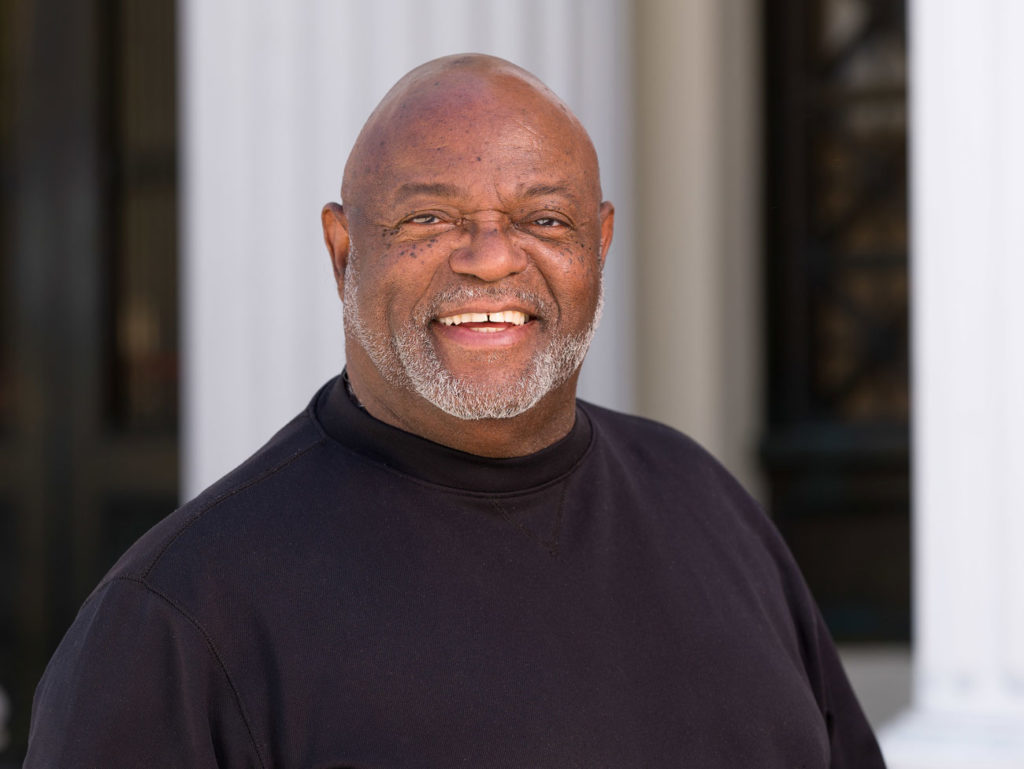

George Tribble ’71, MBA ’72, remembers a particularly quiet, beautiful day on campus. And while he doesn’t recall where he was going when a large car stopped to pick up a female student, Tribble never forgot what he saw.

A popular, outspoken student, Tribble played football and wrestled for the Aggies from 1968-69, and was active in student government, serving as athletics vice president in 1970. Tribble had completed his bachelor’s degree and was working on an MBA in finance. Honored as USU’s Man of the Year in 1971, Tribble was instantly recognizable on campus, so when the young woman smiled at him, he instinctively started to wave back. But just as he did so, he says he briefly locked eyes with the driver, whom he believed to be the woman’s father.

“He reached over the back of the seat and slapped the holy living hell out of the girl,” Tribble recalls. “I felt so bad for the girl, who was someone I didn’t necessarily know, but she knew me.

“But,” Tribble adds quietly, “sometimes just knowing the wrong people can get you in trouble.”

Tribble, a longtime mortgage broker in the Bay Area, was a heavily recruited running back who almost attended the University of Southern California.

“But my father, who was a minister, said, ‘Son, you gave them your word,’ so I stuck with my decision to come to Utah State, and I have never regretted that decision,” Tribble says. “I had a lot of fun up there, and still have a lot of friends I made while I was at USU.”

One such friend is Roietta Goodwin ’71, a native of Ogden who came on an academic scholarship in 1966. Now Roietta Fulgham, she teaches business at colleges in California, and she still gets together regularly with other Aggies like Tribble who live in Northern California. Although she wasn’t an athlete, Fulgham gravitated towards Black athletes because she was also African American.

“I actually wanted to go to a Historically Black College, but that was too expensive for my parents at the time. But it was good because I was able to make lifelong friendships that started the first day of college.”

And being close friends with football and basketball players, Fulgham says she personally felt “protected” while at Utah State.

“I didn’t have any fears while at USU because the Black students stuck together,” says Fulgham, whose son, Kendall Youngblood ’92, played basketball for the Aggies and was inducted into the USU Intercollegiate Athletics Hall of Fame in April 2020. “We often had our classes together and met up in the student union regularly. I don’t recall any blatant attacks on anyone like it is today. I remember that just having the appearance of the large football players and the tall basketball players seemed to keep White students at bay.”

“Maybe things happened behind the scenes since I lived in the dorm and had to be in by 10:30 p.m. during the week, and I usually went home to Ogden on the weekends. I heard years later that some athletes had incidents with fraternities and being called names from visiting teams, but I never saw any scuffles.”

CHANGING TIMES

While Maceyo Vaughan wasn’t able to continue as a basketball player at Utah State, the next wave of Black athletes seemed to be more readily accepted as students at the predominantly White institution. Louis Jones ’57 played varsity football for Utah State from 1955-57, while Overton Curtis ’59, was a star halfback and kick returner in 1958 and ’59, and also pitched for the Aggie baseball team.

On the hardwood, guard Sam Haggerty ’61, M.S. ’67, and forward Harold Theus ’67, were brought in by head basketball coach H. Cecil Baker in 1957.

“That’s when the real turnaround came was in the late ‘50s,” says Ross Peterson ’65, a longtime USU administrator and history professor who was a student at the time. “Theus and Haggerty were both junior college transfers from California, and they helped turn a mediocre program into a 19-7 season in 1958-59.

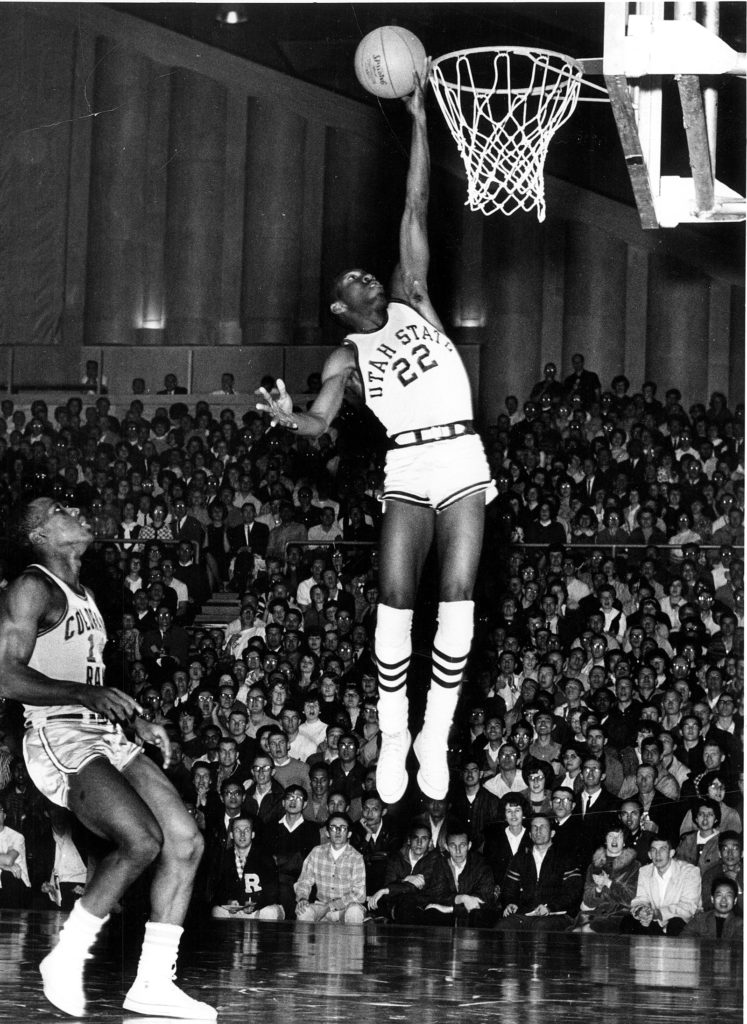

As the ‘60s began, USU head football coach John Ralston turned to his native Bay Area for recruiting, bringing in star running back Buddy Allen and defensive end and future Green Bay Packer Lionel Aldridge. And the basketball team, which moved on from Baker to Ladell Andersen in 1961, also brought in some standout Black athletes from Northern California, including Cornell Green, Tyler Wilbon ’81, and Charles Belcher ’62, who became the first Black student to be voted in as a student body officer when he was elected vice president in 1961.

Wilbon and Green helped elevate the basketball program to new heights, putting together a 24-5 season in 1959-60 that ended with the Aggies being ranked eighth in the final Associated Press Top 25 poll — still the highest finish in school history.

Fans noticed. They noticed other things, too. And they wrote to university administrators to let their feelings known about Black athletes receiving scholarships and dating White women.

“Although small in number, black male students were particularly visible because of their high profile on athletic teams,” Nelson noted in her thesis. “In line with Michel Foucault’s notion of surveillance by those in power, the administration monitored the grades and dating habits of the school’s male African American students as a separate demographic.”

Now 81, Green lives in the Dallas area where he starred as a defensive back for the Dallas Cowboys for 13 seasons, despite never playing football in college. The two-time All-American recalls positive memories of his time at Utah State, “But you knew that they knew that you were Black.”

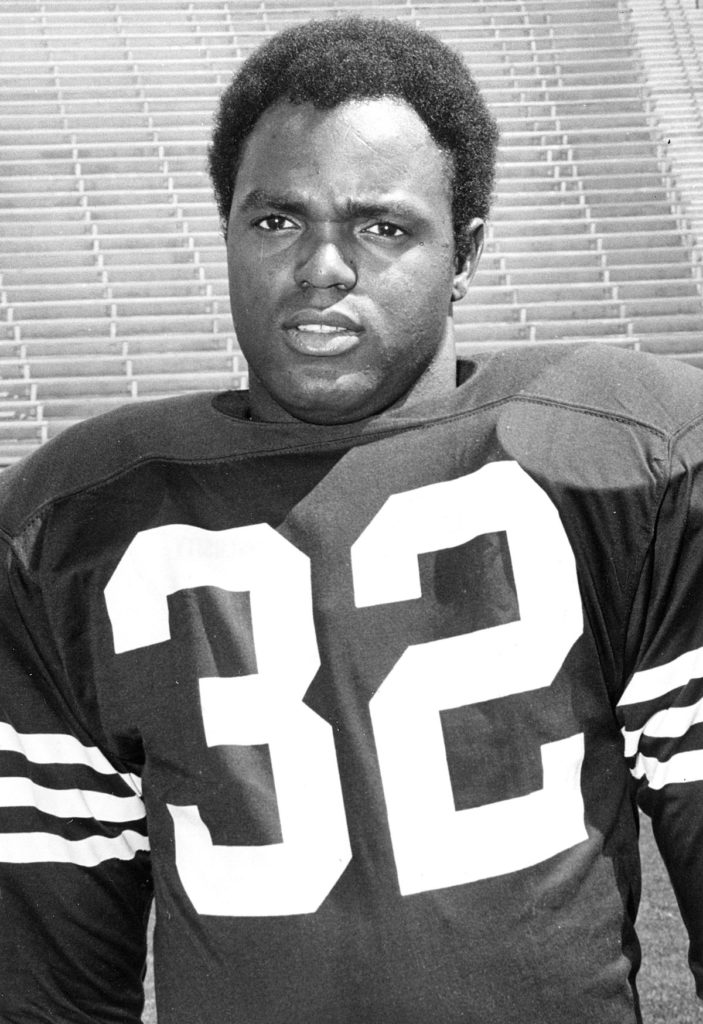

“I don’t have any regrets. I was treated well there, as well as can be expected for a college kid,” Green continues. “I didn’t really encounter any real racial incidents, other than when Darnel Haney ’65, M.S. ’73, got in a fight when we were playing against BYU.”

He is referring to a particularly heated game in February 1961 at the Nelson Fieldhouse where multiple tussles occurred, including one between the 6-foot-8 Haney and BYU center David Eastis.

During a 2006 interview for USU Special Collections and Archives, Haney said of the fight: “You know, I think that was a psychotic break that I had with the pressures that were on me. I’ve been called nigger 10,000 times on a basketball court, I would say. ‘You block this nigger’s shot,’ and go on with it. But with all the pressures that build up inside of you, it wasn’t BYU, it wasn’t that at all, it had nothing to do with it, it was just my emotions that had been building for months and all the pressures of the community. The hate that I received. How long do you maintain?”

The insults Haney experienced didn’t just occur on the court. During the interview, he described hearing a biology professor saying, “there must be a nigger in the wood pile.”

Haney, the son of a domestic worker, grew up helping support his family of 12 with odd jobs after his father was murdered. He earned his master’s in sociology at Utah State in 1973 and became one of the first Black full-time employees at the university before going onto a long career in higher education administration at Weber State.

“But if you go over and look at the president’s mail at USU, you’ll find more hatred mail towards Darnel Haney than I’ve ever seen,” declares Ross Peterson, who taught U.S. and African American history at USU from 1971 to 2004.

INTERRACIAL DATING

The hate mail about Darnel Haney received by USU President Daryl Chase had more to do with Haney’s activities off the court.

While taking a class at the Art Barn, Haney met Marie Packer, a local White girl, and the couple started dating in the summer of 1960. According to Peterson, once they were told about the romance, Marie’s family decided that they wanted the couple to continue to date out in the open.

“It was a very painful, lonely year for me; even many of my Black friends would not talk to me,” Haney told interviewers. “They were afraid because I was causing trouble for them by interracial dating. See all those guys were dating interracially too, but they weren’t doing it openly.”

In fact, it was discouraged at the highest levels. In January 1961, USU President Daryl Chase met with Black students to discourage interracial dating.

According to Haney, when Ladell Andersen ’51, took over as coach in 1961, he was told to get rid of the big forward.

“And he said, ‘If he goes, I go.’ He stood up for me and he fought for me,” Haney said. “These are things I learned later. … Friends were afraid for my safety. They thought maybe somebody would try to do something to me. I had no idea about those things.”

Darnel and Marie married in 1962 and are still together nearly 60 years later. But their relationship — and the accompanying hate mail received by President Chase — underscored racist sentiments simmering beneath the surface.

TEAMMATES AND BROTHERS

In a 1986 essay entitled “Civil Rights in Cache Valley,” former USU archivist Bob Parson ’81, M.S. ’83, quotes a letter sent to President Chase in 1961:

“Let’s give basketball back to the white boys … The practice of going out and recruiting colored boys and eliminating our boys is indefensable (sic) and should be abolished. … They are no permanent good to the University and in most cases the University is no good to them.”

New head coach Ladell Andersen recruited Black student-athletes anyway. Players like Cornell Green and Troy Collier ’64, who went on to play for the Harlem Globetrotters, and LeRoy Walker.

In 1964, Walker, who had never left the Bay Area, was on a train headed for Salt Lake City. While he was roommates with Collier, it was a 6-foot-6 White kid from Montana well on his way to becoming the school’s first 2,000-point scorer that Walker became closest to. He documented his friendship with Wayne Estes in the 2012 book Wayne and Me.

“We just hit it off,” Walker says. “We were just two silly guys who had a lot of similarities on and off the court. We even had the same taste in music. ‘Baby Love’ by the Supremes. Wayne just loved that record.”

Their friendship came to a tragic end on Feb. 8, 1965, when Estes was killed after stopping at the scene of a car accident near the bottom of Old Main Hill. Walker came along just minutes after Estes’ forehead had brushed against a downed power line. He’ll never forget seeing his friend laying on the ground.

“When we got there, he was still smoking,” Walker says quietly. “It was horrible, man.”

While the USU community reeled over the loss, the Aggies played the remainder of their schedule and the high-flying, 6-foot guard dedicated every game to the memory of his fallen friend.

Despite the tragedy of Estes’ death, Walker says his experience at Utah “was the best two years of my life.”

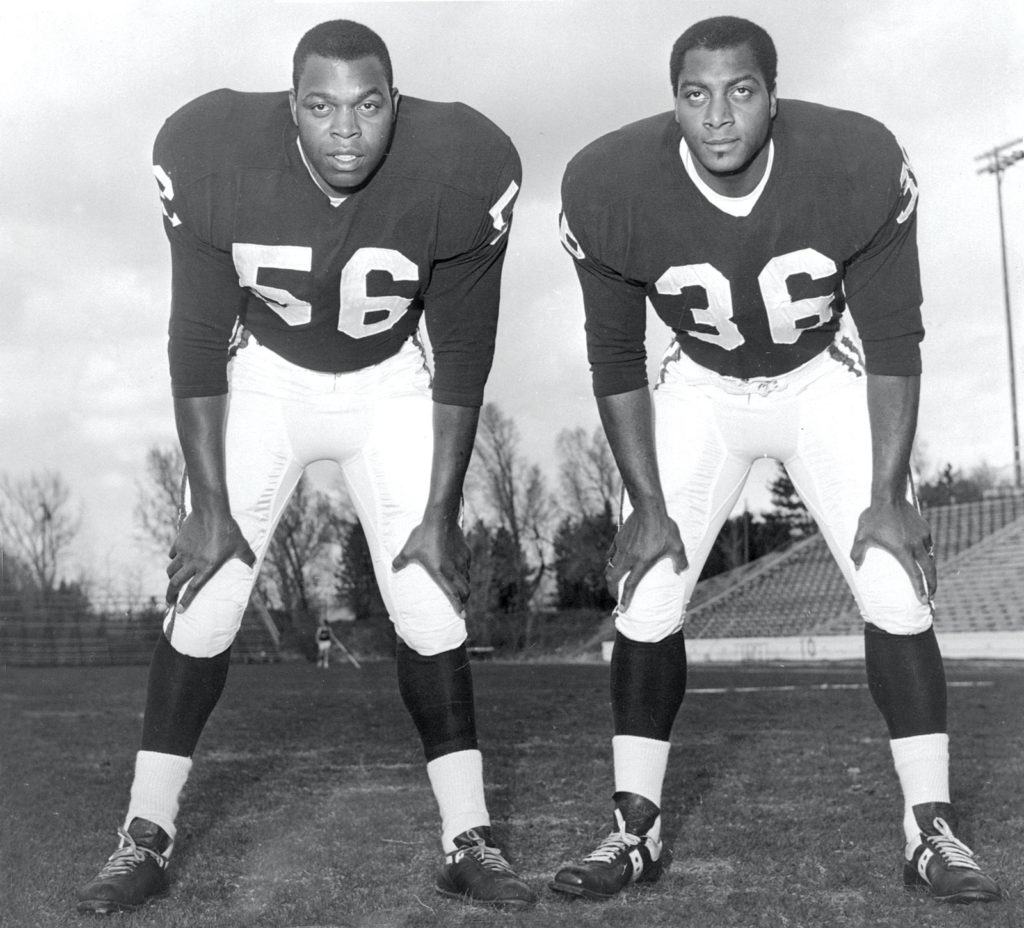

Phil Olsen ’70, and Sid Lane, ’70, are part of two of the most well-known sibling combinations in Aggie football history. Phil’s brother, Merlin ’62, M.S. ’71, a Hall of Game defensive tackle for the Los Angeles Rams, and Sid’s brother, MacArthur, was a star running back who went on to play 11 seasons in the NFL. They also call each other “my brother.” But Olsen is White and from Logan, and Lane is Black and from the Bay Area.

“We still talk all the time, and he’s closer to me in many ways than members of my own family,” Olsen says. “And I think he feels the same way.”

Olsen didn’t have a Black teammate until he got to college at Utah State. However, in the ‘60s the Olsen home in The Island neighborhood of Logan was a gathering place for all football players — Black and White — where Olsen’s mother Merle regularly fed them on the weekends when the school cafeteria was closed.

“My mother loved everyone and always saw the best in everyone,” Olsen says. “But she really loved Sid.”

After Lane graduated, head coach Chuck Mills hired him as an assistant coach, which records suggest made Lane the first African American football coach at the Division I level. Lane credits Coach Mills and Utah State for the honor. “I believe they didn’t hire me because I was the first Black coach, but because it was me. Color had nothing to do with it, for sure,” he says.

Lane, who turned 81 in April, says he and his brother used to talk about their fond memories of their time at Utah State before he died in 2019.

“To be honest, I really only went to Utah State to play football, but all of a sudden I started to realize that I was smart enough to graduate. And Coach Mills said, ‘You are going to graduate,’ so I started working at it, and it paid off,” Lane says. “I think most of the Black ballplayers that went to Utah State feel the same way.”

THE PROTEST THAT NEVER WAS

Until 1978, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had members of color, but it didn’t allow African American males to hold the priesthood—which essentially eliminated them from holding leadership positions—until the church’s president, Spencer W. Kimball, announced a change, allowing all worthy males above a certain age to hold the priesthood.

![pull quote reading: "Let's give basketball back to the white boys ...The practice of going out and recruiting colored boys and eliminating our boys is indefensable [sic] and should be abolished." - A 1961 letter sent to President Chase](https://utahstatemagazine.usu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Pullquotes-ChaseLetter-518x1024.png)

But in October 1969, 14 Black football players at the University of Wyoming planned to protest the church’s controversial practice when the Cowboys played BYU, a school owned by the church, saying they had been subjected to racial epithets during the previous year’s game in Provo. The Wyoming players wanted to wear black armbands for the rematch. But after speaking with head coach Lloyd Eaton, the 14 Black players were dismissed from the team.

What most Aggie football fans don’t know is that something similar nearly happened the following month in Logan.

On May 4, 1969, the Black Student Union (BSU) was formed at Utah State. Following the “Black 14” incident in Wyoming, the BSU met with the idea of organizing an armband protest during the game against BYU on Nov. 15. BSU secretary Roietta Fulgham kept the minutes at the meeting:

“There was a discussion of the Mormon religion,” she wrote. “We are demonstrating against the degrading of the black man by the church. The athletes don’t feel that they should compete against BYU without losing their scholarship.”

Fulgham recorded that the BSU planned to keep the lines of communication open with the university concerning the protest. A few members volunteered to make signs for the demonstration and to write a letter to the church asking for a statement on the church’s policies toward African Americans. The BSU would picket the BYU dressing room, sit together during the game, and hold a press conference immediately afterward.

Fulgham also noted that during the meeting a member of the USU football team read a letter from Aggie head coach Chuck Mills “asking them what they are planning on doing at the BYU game.”

“The black athletes are to give him their answer by noon Monday,” Fulgham recorded.

A member of both the USU football team and the BSU, George Tribble remembers that the issue came to a head prior to the team’s last practice before the game against the Cougars. Tribble says Coach Mills told them, essentially: They were at Utah State for academics and football. They could protest before or after the game, but not on his time. Players who wanted to play needed to be on the field in the next five minutes to practice. The rest were placing their scholarships at risk.

Within a couple of minutes, all of the White ballplayers were out of the locker room and out on the field, Tribble says, “and it was just eight of us African Americans sitting there looking at each other. None of us had the ability to pay for scholarships at that time, so we all hurried and got dressed and rushed off to practice.”

While the BYU protest failed to materialize, the BSU continued to grow and thrive, helping lead to the hiring of the university’s first Black professors including, Larzette Hale, who was hired in 1971 and spent 13 years as the head of USU’s School of Accountancy. They also brought notable African Americans like boxing champ Muhammad Ali, comedian-turned-activist Dick Gregory, and Gladys Knight and the Pips to showcase diverse talents in the African American community to Utah State students.

In the end, Tribble says he and his Black teammates learned a valuable lesson, thanks, in a large part, to each of them having a telephone conversation the night of the non-protest with the mother of teammate Tyrone Couey, ’71.

Passing the phone around, Mary Couey told her son’s teammates, “‘Right now you are young, and no one knows you at this point,’” Tribble remembers more than five decades later. “‘And if you don’t complete your college education, you won’t ever have a voice because it’s already difficult for you to have a voice as a Black person. And if you don’t have an education, it will be even tougher for you to have a voice that people will listen to.’”

Mary Couey grew up a sharecropper on a farm in Tennessee, as did Ty Couey’s father, Fred. But Fred Couey eventually served as the personal assistant to Ralph Bunche, the first African American to win a Nobel Peace Prize who was then serving as the Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations. Fred Couey died in 1963 when Tyrone was just a teenager.

But the things Fred Couey taught his son continue to resonate today.

“When things got tough and hard, my Dad would always say, ‘Life is wonderful, as long as you don’t weaken,’” Couey recalls. “And there were many times when the knees were buckling, and I would hear his voice and those words. And he was right.

“I think we’ve all been in those situations where we wanted to roll over and play dead, but we opted to just hang tough a little longer … kind of like with the pandemic.”

IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Chuck Mills, who died in January at the age of 92, encouraged Couey, who played linebacker his freshman season at Iowa Central Community College, to make a visit to Utah State in May 1968.

But with a foot of snow in Sardine Canyon, Couey had to bide his time in Salt Lake City for a day before an assistant coach could take him back to Cache Valley.

“There were probably four inches of snow in Logan when we arrived, and there I was. I had loads of hair — an Afro — and was wearing shorts, a dashiki and Roman sandals that went up my leg,” Couey recounts. “I’m quite sure they looked at me and thought, I think we made a mistake. Who is this guy?’”

But the USU coaching staff thought enough of Couey to take him to Zanavoo Restaurant & Lodge up Logan Canyon the next morning, and after having steaks and eggs and scones for breakfast for the first time in his life, Couey immediately committed to becoming an Aggie.

“I thought, if they feed you like this, then I’m coming here,” Couey says, then adds with a laugh, “That was the first and last great meal that I had in three years.”

During his time in Logan, Couey says he and Mills had their issues, but developed a mutual respect and then a friendship in later years. And Couey, who helped organize an endowment in Mills’ name in 2014, was drafted by Dallas in the 14th round of the NFL Draft and went to training camp with the Cowboys before being cut.

Off the football field, Couey was a history major who was focused on Black studies.

And after struggling academically when he first got to USU, he turned things around and ended up co-teaching a Black history class with longtime professor Blythe Ahlstrom, ’57, his senior year.

Although Couey says he didn’t experience any serious racism during his time at USU, he does remember feeling like he was “at the Bronx Zoo” when he first arrived in Logan.

“Only, I was inside of the cage, and the people were looking at me,” Couey says. “And it wasn’t really their fault, a lot of folks in Utah hadn’t ever seen a real-life Black person before in their lives. But it was very painful. You felt like the spotlight was always on you.”

The first of Fred and Mary Couey’s 10 children to graduate from college, Couey carved out a long and successful career in banking, oil, and computers. But while his daughter was attending Hampton University in Virginia, he helped found the National Historically Black Colleges and Universities Alumni Associations Foundation in 2003. Couey currently serves as the president of the organization that seeks to create partnerships with government, as well as communities, civic groups, and churches to expand, develop, and advocate for HBCUs and their alumni.

He hopes to organize a partnership between Utah State and an HBCU.

“I think it would really benefit this country to have two unlikely characters come together to work on some issues,” Couey explains. “We need to heal because things are crazy right now.”

Couey never forgot a class he took from political science professor Dan Jones in which he taught that “when people have power, they’ll do everything in their power to remain in power.”

“In the context of Black-and-White issues, I took that to mean that he was saying that if the White man is in charge, he’ll do everything he can to remain in charge, regardless of what Blacks or anyone else tries to do to fix things and make things right,” Couey says. “And that’s stuck with me for all of these years, and after what happened at the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, I understood exactly what he meant when he made that statement to me in ’68.”

PERSEVERING

Maceyo Vaughan insists that he isn’t bitter about what happened to him at Utah State.

“I just understood that that was the culture, and I wasn’t angry,” he says. “Evil and ugliness do not live in my heart.”

But without a basketball scholarship, Vaughan couldn’t complete his college degree. He spent most of the next school year working as the sports editor and music critic for the Student Life newspaper and he also helped spearhead an on-campus fundraising drive. But by March 1956, he dropped out.

“I just didn’t have the money to continue, so I left owing money,” Vaughan says. “I tried, but I couldn’t get a job anywhere in Logan because they were given to local people and not people like me.”

In 1956, being a young American male who wasn’t attending college meant Vaughan lost his deferment and was headed towards a stint in the military. He served four years for Army Intelligence in Washington, D.C., before working for the National Security Agency. Vaughan then spent decades working in the private business sector before embarking on a career as a consultant and an inspirational speaker. He traveled around the world into his mid-80s speaking to CEOs, presidents, and upper-level managers about the importance of diversity and inclusion in the business world.

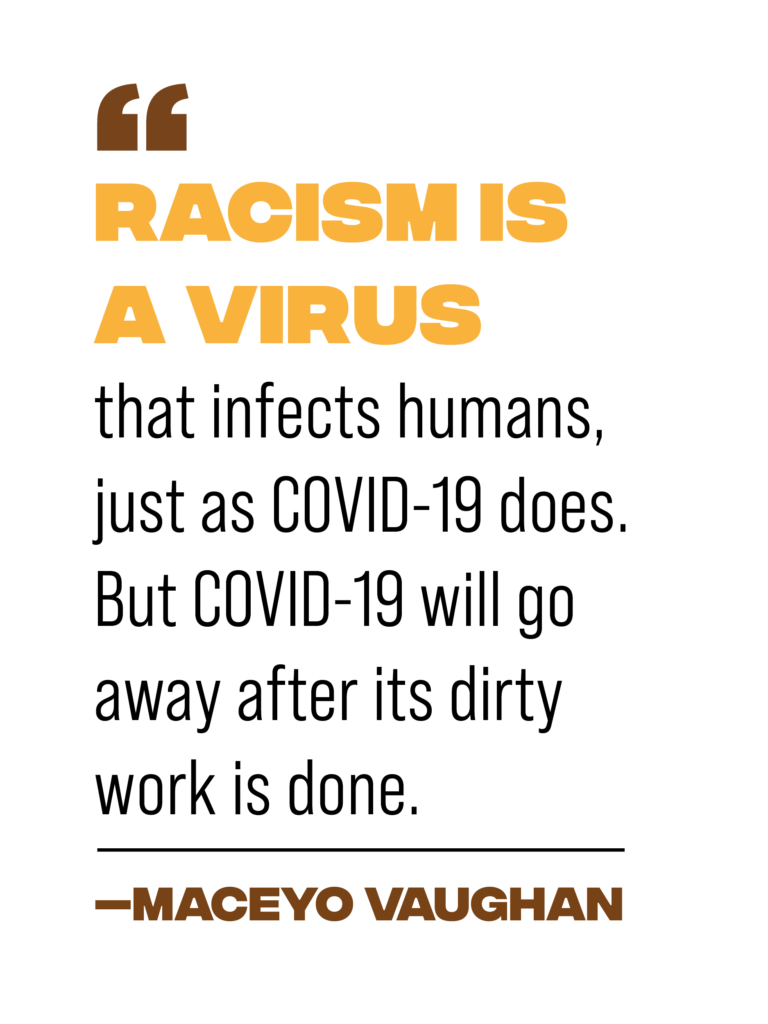

Vaughan, like most of the former USU students contacted for this story, was initially interviewed just before the rise of the coronavirus in March 2020 and prior to the murder of George Floyd beneath the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin in late May. While the list of incidents involving police brutality against unarmed African Americans is tragically long, Floyd’s death in Minneapolis was the impetus for a renewed effort to combat systemic racism in the United States.

The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement and highly visible protests throughout the country, primarily during the summer of 2020, occurred concurrently as COVID-19 was disproportionately affecting communities of color.

The sadness evoked by this challenging period is evident in a short essay Vaughan wrote in August 2020. Normally an upbeat and optimistic individual, Vaughan entitled the piece, “Our Lady Democracy Weeps.”

“Racism is a virus that infects humans, just as COVID-19 does. But COVID-19 will go away after its dirty work is done,” Vaughan wrote. “Racism lives on doing its evil work, and the price our society pays for it is galactic. There are about 48 million Blacks in America and one wonders why a country would allow, and in some cases prefer, such citizen alienation. Where is the sanity in that? Lady Democracy weeps because we cherish her wisdom and her bounty while abusing some by rationing its application and expecting good outcomes.

“The heinous Klan existed because it was allowed to exist. The mafia existed because it was allowed to exist. And today’s racism exists because it is allowed to exist,” Vaughan continued. “We have the capacity to rid our country of racism, sexism, and all other ugly destructive behaviors. The only question is do we have the will?”

THE PATH FORWARD

While Utah has not been at the center of tragic events sparking national conversations in recent months like Minneapolis, Louisville, and Kenosha, USU President Noelle Cockett recognized that the university community has an opportunity and responsibility to do its part to better understand and counteract racism. The theme of last year’s annual Inclusive Excellence Symposium was “Black Lives Matter: A Community Calling” and featured sessions dedicated to the realization that issues of equality, economic security, and physical safety for members of the Black community continue in the 21st century and must be a part of our university’s civil dialogue.

Cockett created a Diversity and Inclusion Task Force in spring 2019 to create a strategic plan for diversity and inclusion at USU, and the university released its first campus climate survey on diversity and inclusion in May 2021. She will add a cabinet-level leader to help focus and guide USU’s diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts by spring semester 2022.

And on the USU campus in the summer of 2020, former head football coach Gary Andersen and members of the Aggie football team were inspired to learn more about racism in America, leading to the creation of a new class entitled, Untold Truths of African American Inequality in the United States. The course was taught by Ross Peterson, who first developed a zeal for teaching African-American history while at the University of Texas Arlington from 1968 to ’71.

“The school had barely been integrated then,” Peterson recalls. “The state had broken down a lot of the barriers by the time I got there – and it wasn’t still the Deep South – but we might have had one African American on the football team when I got there.”

“That became a real passion; something that I’ve always done here at Utah State, too,” said Peterson, said of teaching about the Civil Rights movement.

More than 50 years later, Peterson, who is semi-retired, taught the inaugural Untold Truths of African American Inequality in the United States course last summer, which presented the evolution and history of racism in America, how it has affected past and current generations of people, and what can be done about it going forward. As part of the class, Peterson invited former Black Aggie athletes like Darnel Haney to share their stories with the nearly 50 students, the majority of them football players, who enrolled in the course.

“The idea was to create an understanding of the world we live in today through finding historical roots,” Peterson says, who will teach the class again in the fall of 2021. “How does this exist in this country, of all countries? Where does it come from? And how do we understand it?”

And how do we move past it?

By Jeff Hunter ‘96

Roietta Goodwin Fulgham August 17, 2021

This article in the USU magazine brought back other memories for me too in addition to what Alvin and Roger stated. On my first day on campus at USU in 1966, my roommate Mary Graham Shields took me to the student union where I met Altie Taylor and Frank Nunn. Many study opportunities were held in that student union along with friendships, class discussions, conversations, card games, and pool—I got my pool skills from MacArthur Lane. I also enjoyed going to games and knowing other athletes like Roy Shivers, Ocie Austin, Henry King, Wes Garnett, Shaler Halimon, Fred Smith, Ed Epps, Jimmy Smith, and Lafayette Love. Being able to cheer for Zetta Satterwhite Hall along with others at her tryouts to be an Aggiette was a memorable experience. Thanks to Malcolm Wharton, we saw photos of Black and Brown students (like the one on the cover of the USU magazine) displayed in the student paper, ads, and yearbooks. I also want to thank Joanne Yamasaki Adair—our USU study buddy–for continuing to be a friend over these last 50+ years.

Michael Phillips August 6, 2021

Outstanding!! The article describes your and your fellow black student-athletes experience during that period so objectively and straightforwardly it made for enjoyable reading regardless of the subject matter. Tyrone, I am so impressed by what you’ve accomplished and continue to accomplish . It makes me even more appreciative of our friendship..

Alvin Reiner August 5, 2021

While at USU I was the photo editor of “Student Life” and had the opportunity to cover several notable Black speakers on campus: Mohammed Ali, James Farmer, Julian Bond and Dick Gregory. (I photographed Gregory again a few years ago shortly before he passed away.) I was also fortunate to photograph basketball players Marvin Roberts and Nate Williams. I believe a fellow photographer, Malcolm Wharton, whose work appeared with mine in the USU literary publication, “The Crucible”, gained prominence in photography.

I also remember when the Prophet Seer and Revelator of LDS Church apparently had a revelation that Blacks could hold the ministry after the U of Wyoming once again refused to play in Utah.

Alvin Reiner, USU Natural Resources Class of1972.

Roger Nestel August 5, 2021

Hi Al Very interesting expo on the historyof USU. I also have a copy of the Crucible 1970 It brings back old memories class of’72 forest management