Rise of the Machines

It’s Monday, November 2, 2020. Polls open in 24 hours for the next presidential election after a grueling campaign season.

While thumbing through the news app on your phone, a viral video of your candidate pops up on the feed of a major television news broadcast. Your presidential pick is caught saying something so over-the-top outrageous, any chance of winning has evaporated. You heard it. You saw it.

Except it never happened. The video was fake. Not created by a talented editor, but by a machine. An intelligent machine. Although this scenario hasn’t yet materialized, the use of artificial intelligence (AI)-generated fake news being unintentionally broadcast by mainstream media could happen. And soon.

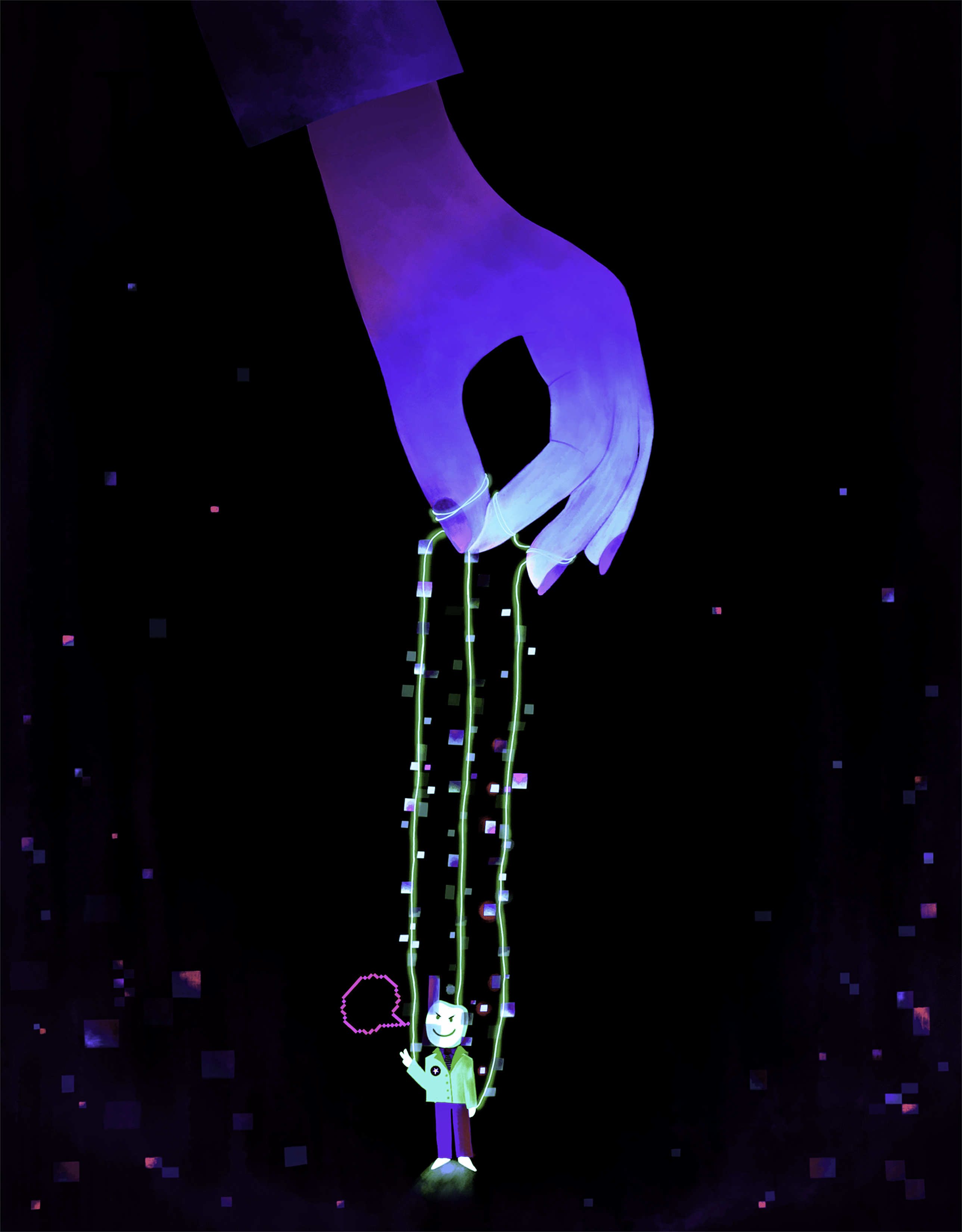

Readily available technologies that produce realistic images, audio, video, and text already exist and make differentiating these digital fakes from real content increasingly difficult. The use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)—a machine learning system where neural networks compete to generate new, improved data—makes it easier for bad actors and provocateurs to spread disinformation.

Should this scenario come to pass: How does the Fourth Estate recover from the loss of trust that is so vital for democracy?

Deepfakes emerge

The manipulation of photographs for political purposes has been a phenomenon since President Abraham Lincoln’s head was placed onto the body of South Carolina statesman John Calhoun’s body in a lithograph in about 1865, if not earlier. AI technologies are the next frontier.

In December 2017, Motherboard was the first media outlet to write about AI-assisted fake videos. The story focused on Deepfake, a Reddit user who used GANs to produce illicit videos by swapping the faces of celebrities to actors in an existing pornography video.

Since the story was published, technologies to effortlessly manipulate images and videos have developed at a breakneck pace. Commercially available, easy-to-use products such as FakeApp—created by Deepfake—allow individuals with relatively little technical expertise to swap faces on videos or transmit in the voice of virtually anyone, including world leaders. In April 2018, it took just hours for a nontechnical person to create a lifelike video mimicking former President Barack Obama using source video of another person. A new deepfake algorithm from researchers at Heidelberg University can render more accurate human physical behavior, essentially creating virtual body doubles.

Unfortunately, there’s more.

The creation of entire synthetic news reports and scientific papers written in the hand and vernacular of human beings is the latest deepfake technology. For example, OpenAI, a San Francisco based non-profit founded by technology entrepreneur Elon Musk, debuted a news story written by an AI program that is striking in terms of its composition quality and alarming in that none of the facts within it are true. The program worked so well that a recent story in Ars Technica described OpenAI researchers restricting the public release of the code in an attempt to curb the use of the technology for harmful purposes.

The technology used to create deepfakes is relatively straightforward. The technique uses a machine learning method that relies on patterns and inference. The GANs used in the creation of deepfakes consists of two artificial neural networks that simulate biological neural networks and compete against each other in a form of unsupervised, iterative learning. One GAN generates a candidate, and the other GAN evaluates the generated candidate. Each GAN learns from the previous interaction and makes improvements based on what it has learned. Plainly, GANs enable the construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of video frames until the end image is nearly indistinguishable from a real image.

Unsurprisingly, concern has migrated from the victims of fake, profane videos broadcast in relatively obscure websites to content that may jeopardize national security and democracy.

An imminent threat

Earlier this year, the Director of National Intelligence testified before the U.S. House Intelligence Committee that bad actors from hostile nations are expected to use deepfakes to “sow discord and breed doubt.” The ease with which deepfakes can be generated by bad actor upstarts, state-sponsored or otherwise, has created a sense of urgency within national security circles. Knowing how to identify and stop the dissemination of deepfakes as part of influence campaigns has become a priority. The range of hostile uses of deepfakes is limited only by the imagination.

Jeannie Johnson ’93 MS ’95, associate professor of political science and director of Utah State University’s new Center for Anticipatory Intelligence (CAI), says a potential use of weaponized deepfakes would be to incite anger against United States armed forces.

“This would be an effective tactic for undermining US public support of its military abroad, as we have seen in actual cases like Abu Ghraib,” she says. “It would be a very attractive tactic for those who cannot defeat our forces on the battlefield.”

Johnson, a former analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency, co-founded the interdisciplinary center with Matthew Berrett, a former CIA assistant director, and Briana Bowen ’14, CAI’s program manager. The new certificate program teaches students to identify the unintended consequences of emerging technologies. (Disclosure: I am a member of CAI, too.)

If a deepfake does make its way into the media, the damage may be irreversible even after it gets exposed as a forgery. There is no guarantee that individuals who view a deepfake on a particular candidate will see a correction or rebuttal.

Berrett argues democracies need facts to deliver the greatest good for the greatest number—facts about the competence, values, and intentions of political candidates. He questions what would happen to the effectiveness of democracies, and their appeal to humanity, if facts are removed from voting and policy.

The democratization of state-of-the-art deepfake tools represents a paradigm shift in image, audio, video, and text manipulation once reserved to experts in software such as Photoshop and After Effects. Research has shown that intentionally false information diffuses significantly farther, faster, and deeper than accurate information via social media, meaning millions of Americans are vulnerable to potential influence campaigns by rogue actors. This poses a unique national security threat as experts worry deepfakes could be a useful tool to undermine democratic elections and sow confusion on the cyber battlegrounds. The Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank in United States foreign policy and international affairs, suggests deepfakes could also be deployed publicly in military operations or used to derail diplomatic efforts.

Propaganda attacks are hardly new to nation-states, which will have technical tools and intelligence means able to discern whether a piece of video or audio is real, Berrett says. “But, a deepfake emerging during international tensions, particularly in the increasingly fact-free, bias-driven political environment we’re seeing East and West, could ignite popular anger to the point of forcing leaders to act more aggressively than they would otherwise.”

Some security experts warn that deepfakes will be virtually impossible to detect by the 2020 United States elections.

In the book Likewar: The Weaponization of Social Media author Emerson T. Brooking reported that the St. Petersburg, Russia-based Internet Research Agency produced more than two million election-related tweets in the closing months of the 2016 election. At the Reagan National Defense Forum last year, former Secretary of Defense James Mattis said Russia is likely planning deepfakes to supplement an already robust disinformation campaign to incite chaos during the 2020 elections.

If a deepfake does make its way into the media, the damage may be irreversible even after it gets exposed as a forgery. There is no guarantee that individuals who view a deepfake on a particular candidate will see a correction or rebuttal. And even if voters are given unimpeachable evidence that a video that contradicts their point of view is fake, it may be inconsequential.

Often fake news serves to strengthen a preconceived idea or belief. In fact, particularly fervent ideologues may see attempts to discredit deepfakes that support their beliefs a conspiracy.

How will the Fourth Estate protect itself from airing deepfakes?

A weakened gatekeeper?

The role of the free press as a pillar of democracy in the United States is enshrined in the First Amendment of the Constitution. Traditionally seen as gatekeepers of information, the media’s attempt to produce completely accurate information is a demanding standard to meet, and continues to be eroded by new modes of news consumption. To compete in the 24-hour media landscape, pressures mount to produce news as it happens and funnel targeted audiences to a directed source.

The American public has traditionally relied on the mainstream news media (MSM) as their primary source of information. While there has always been bias in certain sectors of the Fourth Estate, much of the media has attempted to provide accurate, unbiased information by which citizens are better-informed participants in public discourse and democracy. However, trust in mass media is diminishing. It went from a post-Watergate high of 72 percent in 1976 to a low of 32 percent following the 2016 election.

Most citizens do not trust the media to verify facts.

Most citizens do not trust the media to verify facts. In 2016, a Rasmussen poll of voters found that 62 percent of respondents believed that mainstream journalists misrepresented details to benefit political aspirants they supported. Similarly, a 2018 Gallup poll that rated America’s most prominent societal institutions showed that television news and newspapers ranked near the bottom of trustworthiness. Television news ranked just above the least trustworthy institution—the U.S. Congress. The ascent of fake news, together with decreased confidence in the MSM, underscores the importance of the MSM to distinguish itself and serve as a harbor for credible information.

The phrase fake news has become commonplace since the 2016 presidential election, but there is no consensus among scholars as to the definition of fake news.

As a public relations director within the space and intelligence industry and a couple of decades working closely with the media, I consider fake news as that which has been created with the intent to deceive the public for malicious reasons; a definition that does not extend to news that a particular individual simply finds objectionable. Purveyors of fake news do not adhere to ethical guidelines outlined in the Society of Professional Journalist’s Code of Ethics that have become the media industry standard—to seek truth and report it, minimize harm, act independently, and to be accountable and transparent.

In January 2019, Seattle Fox television affiliate KCPQ unknowingly aired a doctored speech of President Donald Trump’s January 8 televised address from the White House. The altered video of the speech was made to make Trump appear as if he had carotenosis, and his mouth movements were slowed to create an effect where his tongue appeared to linger after he talked. In May 2019, another fake video of an American politician went viral on social media. This time it was a manipulated video speech of Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi altered to make her appear intoxicated as she slurred her words.

Matthew LaPlante, associate professor of journalism at USU and a veteran reporter, tells his students that ‘mainstream media’ has never been mainstream and that fact-based reporting without fear or favor is a relatively new innovation. In fact, LaPlante points out that late 19th century New York congressman and media mogul Joseph Pulitzer helped lead us into the Spanish-American War with sensational stories and exaggerated tales of what was happening in Cuba.

“[Media] has always been a reflection of the needs and values of the people who own it and create it,” LaPlante says. “It has always been easier to tell lies than truths, and it’s particularly easy for those with the means of power to share stories.”

Sometime during the 20th century, Americans expected the news they consumed to be accurate, and without hyperbole. “People who are committed to telling stories that are true have always been at war with the forces that conspire to deceive us,” LaPlante explains. As to ensuring the media remains trusted gatekeepers of accurate information, LaPlante says, “If you’re going to share a piece of information, trust no one and trust nothing. Verify. Verify. Verify.”

“If you’re going to share a piece of information, trust no one and trust nothing. Verify. Verify. Verify.”

Some news organizations are already buffering themselves against the rise of deepfakes. The Wall Street Journal has convened an internal forensics committee trained in deepfake detection using conventional video editing software and is exploring AI solutions with academia to expose deepfakes more precisely. Other large news companies have initiated similar pursuits.

“However, smaller organizations may have trouble keeping up with advances,” says Brooking of Likewar. “While there are technologies that can detect deepfakes, they may not be available to all newsrooms,” he cautioned. ”And, given the intense time crunch that modern newsrooms face, they may not always employ these tools even if they possess them.”

One concern is that conventional journalists may not have the required knowledge and tools to keep up with advances in the way information is created, distributed, and consumed. If MSM loses the ability to produce trustworthy information, it will become irrelevant.

But, just as technology has created this problem, perhaps it can help solve it.

Resiliency in the media

At last year’s Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance, the use of forensic AI technologies such as recurrent neural networks, where a program learns to identify videos that have been manipulated, showed promise in the ability to detect deepfakes. And in 2018, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency reportedly spent $68 million on its media forensics program to detect deepfakes.

However, it’s not hard to imagine an AI arms race where developers create increasingly sophisticated tools to create and debunk deepfakes.

“These sorts of things are what academicians, lawyers, and scientists should worry about,” says David E. Brown, an associate professor of mathematics and statistics at USU and an expert in the areas of AI and robotics. “A machine doing something malicious because it thinks like us will never happen.”

Malicious intents carried out by programs or apps designed by people answering a ‘could we’ question, and disregarding a ‘should we’ question, is feasible, and has been for a long time, he adds. “AI alarmists seems to be misdirecting our attention, the true threats are not on the horizon; they’re with us now and we’re doing a terrible job mitigating them.”

Relying on technology to uncover is not a foolproof solution.

some within the technology industry argue deepfakes will play an essential, positive role in business and entertainment, and that the intelligent automation of processes, such as writing and reporting, is a timesaving tool. But cracks in the foundation are showing. In their most recent Securities and Exchange Commission filings, Alphabet Inc., the parent company of Google, warned that their use of AI and machine learning could raise ethical challenges for them, signaling to shareholders the risk of potential ethical liabilities by using AI and machine learning in their services and products.

Often when one thinks of fake news, you think of content appearing on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook. While fake news in social media creates a unique environment where it thrives, MSM is not impervious to transmitting fake news, and the consequences of publishing fake news from bad actors is not evenly distributed. For the MSM, it may deepen public mistrust and is why resiliency tools are needed.

Some are, to some extent, already in place, including editorial discretion and emerging AI technologies to find deepfakes before they are disseminated. However, news organizations may need to be more aggressive in how they explain their methodologies and editorial processes to the public. While large news organizations have the resources to create committees and deploy technology to combat deepfakes, news organizations in small to mid-sized media markets must rely on other methods to detect fake news.

In the event of the inadvertent publishing or airing of a deepfake, the news organization should devote an entire special or series to explain how they were fooled.

USU journalism lecturer Brian Champagne, a prolific stringer for local network news affiliates in Salt Lake City, relies on two independent sources for a single story to help ensure accuracy. He says one of the affiliates has an editorial board that serves as a gatekeeper for accuracy and the other local network affiliates rely on the judgment of the news directors and with informal discussions among other professionals in newsrooms to ensure journalistic integrity.

When fake news does occur in the MSM, several immediate and predictable steps should be taken to regain public trust: A retraction, in which the story is removed online, and a corrected print or broadcast story is published, possibly followed by another story containing an apology from the news organization, and potential procedural changes in the newsroom.

The most important aspect of resiliency for media is intense transparency, Brooking says. In the event of the inadvertent publishing or airing of a deepfake, the news organization should devote an entire special or series to explain how they were fooled. This would serve to illustrate the sophistication of modern deepfakes and double as a public awareness campaign.

Will it be enough?

By Eric Warren

Eric Warren is a director of public relations at USU with two decades experience in the space and intelligence industry. He is a member of USU’s Center for Anticipatory Intelligence, and his academic research encompasses technology-driven disinformation campaigns and its effect on national security.