Pastoral Rising

The Kuchi are nomadic herders in Afghanistan who rely on strong relationships with villagers along traditional migration routes. Photo courtesy of Catherine Schloeder.

The thought of pastoral life can summon nostalgia for a simpler time.

Before humankind began tapping on keyboards. Before the cacophony of a 24-hour news cycle. But roaming the rangeland with one’s herd is fraught with complications. A daily reliance on finding food and water. A seasonal gamble between rain and drought. And the challenges of raising livestock are harder to surmount as a changing climate, population growth, and reduced pastureland compound to threaten a way of life practiced for millennia in parts of Africa. But how do you pivot to a less risky livelihood when you have no savings, no literacy skills, no land?

On the fringe

Layne Coppock has some ideas.

The professor of environment and society at Utah State University has spent 40 years studying the people and rangelands of east Africa. In 1981, while bunking atop a Land Cruiser studying the ecology of nomadism in northern Kenya, he observed herders experiencing chronic hunger, whose only savings was walking on four hooves. This prompted Coppock to consider a conservation model focused less on wildlife and more on the health of pastoral societies, reasoning that without economic stability there couldn’t be ecological stability.

“In some ways, I’m on the fringe in my field,” he says from his office in the S.J. & Jessie E. Quinney College of Natural Resources. Coppock runs his hand through a wave of gray hair. He doesn’t want to talk about his work. But to talk about the efforts of his former students working in Africa today, some context is required. Coppock points to a picture above his desk of an Ethiopian woman loading a homemade kiln with bread and begins.

Nearly 21 years ago, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) funded his plan to promote greater resiliency among pastoralists on the Ethiopian Borana Plateau through investments in human capacity. Historically, pastoral societies could sustainably raise livestock despite periodic droughts. But in recent decades, shrinking rangeland, growing populations, and more frequent droughts wiped out entire herds. Poverty is widespread and government services are limited.

The Pastoral Risk Management Project (PARIMA) hinged on the idea that using participatory research methods—asking people what they need and harnessing local solutions—pastoralists could invest in their communities, and by extension, themselves. In traditional research, you have a theory, you have a hypothesis, and then you produce findings—that’s all top down. With PARIMA, we had more flexibility, Coppock says. This allowed researchers to pivot in promising directions when they surfaced. Like a serendipitous flat tire in a desolate place.

Hope exists

“I was making a first reconnaissance trip in the project area to [get] an updated picture of the pastoral situation,” says Solomon Desta Ph.D. ‘00. “My car broke down in a small pastoral hamlet called Kulamawe, a rock-strewn hot dryland in northern Kenya. While my driver worked to fix the car, I was walking around looking for a tea shop to have tea and shade to run away from the scorching heat.”

He walked into a small mud-roofed hut where he met some local women serving tea. Desta asked how they made a living and they told their survival stories—how they made it through the last drought and kept food on the table and their children in school when others couldn’t. The women ran small businesses and engaged in livestock trade, Desta says. They exemplified the benefits of “diversification for risk management” that he and Coppock studied at USU and ultimately changed PARIMA’s course.

The women developed the capacity to adapt and change to reach a desirable status, not just to recover after drought, Desta says. These women were different from other pastoralists he had encountered.

“They were well organized, liberated, diversified, and willing to invest in their children education and health.” So how did these former nomadic pastoralists thrive in the dry, craggy landscape of northern Kenya? They didn’t do it alone.

After drought wiped out their livestock, the women scraped by selling firewood and charcoal they collected. Many stories would end here. But these women banded together, pooling what limited resources they had, and made microloans to each other to start non-pastoral ventures. This opened the door to further investment, funding needed community services such as health clinics. The women were evidence that economic diversification could help pull pastoralists out of poverty and their collective action groups became a central feature of PARIMA.

Pastoralists throughout the Horn of Africa often face challenges such as shrinking rangeland and more frequent droughts. Photo courtesy of Catherine Schloeder.

Between 1997 and 2009, 59 collective action groups, comprised mostly of women, were established in Ethiopia and northern Kenya. The groups merged their savings and issued more than 5,400 loans to members in increments of $20 or less. Recipients used the funds to start small businesses or reboot livestock production during rainier seasons and maintained a repayment rate of 96 percent. The PARIMA model has been exported to pastoral communities outside Africa, including adoption by Kuchi herders in Afghanistan.

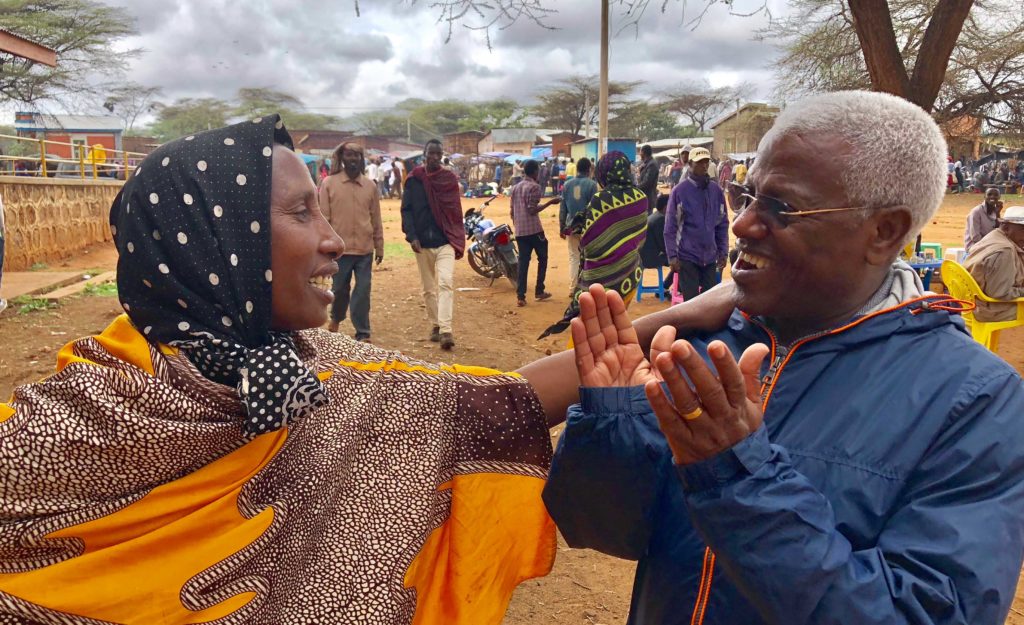

During a visit to the Borana rangelands in 2018, Desta met one of the beneficiaries of the PARIMA project named Insene. She is now a fairly successful business woman, he says. Photo courtesy of Solomon Desta.

Fast forward to 2019, Desta’s latest endeavor is a $540 million investment project by the World Bank and International Fund for Agricultural Development in six pastoral regions of Ethiopia. The Pastoral and Agro-pastoral Livelihoods Resilience Project (PAP-LRP) rethinks rangeland development in Ethiopia over the last half century. Desta served as lead consultant examining what worked and what went wrong in past efforts. His analysis found that projects should be anchored on the concepts of resilience, transformation, and sustainability. He is now working with the World Bank’s project design team on its implementation.

While Desta expects the number of people leaving pastoralism will increase as they look for jobs in the growing urban economy, he argues the future offers hope. There is global demand for livestock products, combined with improved value chain development for meat and milk in Ethiopia, he says. “Despite the increasing factors of vulnerability and resulting pressure on pastoral livelihoods, opportunities remain high.”

He believes pastoralism in Ethiopia will change, not disappear.

After earning a degree in agricultural economics, Desta worked for eight years in the southern Ethiopian rangelands as an economist for a World Bank-funded project. This is where he first met Coppock, then a scientist with the International Livestock Center for Africa in the region. The two connected over a “shared vision for improved pastoral livelihood and environmental sustainability.” This is why Desta came to USU in 1994 to study range economics, and stayed on as a research scientist with PARIMA through 2009. His time at USU spanned two other doctoral students whose paths he would later cross in development circles halfway across the world.

Managing Conflict

Growing up, Catherine Schloeder and Michael Jacobs knew their futures were tied to wildlife conservation. They moved to Ethiopia in 1990 for positions with the Wildlife Conservation Society developing management plans for the country’s national parks. What they didn’t know confronted them upon arrival at Awash National Park. “We literally drove into a gun fight with the pastoralists and the park right between us,” says Schloeder Ph.D. ’00. “We looked at each other and said ‘well, they certainly didn’t tell us anything about how to deal with this in our academic background in the United States.’”

Consideration for local populations affected by wildlife conservation wasn’t yet a mainstream idea. As the couple studied how wildlife and livestock used natural resources, they began working with local communities to learn what issues sparked conflicts. Our management plan is one of the very first in Africa to build relations with communities and try to resolve conflicts, Schloeder says. That plan was tested when the Ethiopian government collapsed in 1991.

“Chaos ensued,” she says. “The public went wild and damaged a lot of government property. Almost every park was overrun. Wildlife shot. Buildings burned. Awash was the only park that nothing happened. And yet it was the first park created and one of the most contentious conversation areas in the country. That got everybody’s attention.”

Other wildlife conservationists wanted to know what were they doing differently. We told them about our efforts to find common ground with local communities, Schloeder says. “Because we don’t believe people should be starving and dying at the expense of a wild animal. There has got to be some middle ground.” The couple authored a book chapter identifying the work the conservation community needed to do: help people displaced by wildlife areas.

“People at that time were saying ‘we don’t do development. That’s not any of our business,’” Schloeder says. “We were saying ‘it is your business. They are better armed. There are more of them. And government bodies are poorly funded, so the people who are trying to protect [wildlife areas] are unprepared. So you will lose.’”

Understanding the role people play in both the park’s ecosystem and management is a lesson that has stayed with them for decades, Jacobs Ph.D. ’00 says. “By removing them, you are actually hurting your chances of maintaining viable populations of wildlife.” They drifted away from a protectionist model of wildlife management to an inclusive model of development. While working on a joint research project at Omo National Park they pursued doctorates at USU. Schloeder focused on wildlife ecology while Jacobs tackled the range ecology.

Jacobs (upper left) and Schloeder (lower left) visit Omo National Park where they conducted a joint research project during their doctoral studies at USU. Photo courtesy of Catherine Schloeder.

In 2005, Texas A&M called with an offer to lead a project, the caveat being they move to Afghanistan where the United States was helping the Afghan government battle an insurgency. But the couple wanted to work with pastoralists again and felt prepared for the challenges ahead. “What we learned in Ethiopia was it is incredibly important to gain the trust of people,” Jacobs says. “Once you gain the trust of those people then there is very little risk involved in what you are doing.”

Even in a war zone. So Jacobs signed on to head the Pastoral Engagement, Adaptation and Capacity Enhancement (PEACE) project funded by USAID, which aimed to improve livestock production of Kuchi herders. Over about 14 months, Schloeder and Jacobs earned the trust of local leaders, and with that, their protection. This helped PEACE researchers identify what was affecting livestock production most. “Sometimes the root reason is not what we think it is,” Jacobs says. “That’s the beauty of spending enough time and gaining the trust of people … there is a much better chance that you will truly get to what the real problem is and work with those people to come up with the right solutions.”

Michael Jacobs and Catherine Schloeder spent six years on the USAID-funded PEACE project working to reduce economic risk for Kuchi herders in Afghanistan. Photo courtesy of Schloeder.

The largest factor hurting production was the erosion of longstanding relationships between Kuchi herders and farmers along traditional migration routes. In the past, a Kuchi herder and his family would spend months stopping in villages along their passage into the mountains, Jacobs explains. While their livestock grazed, the herders would help plant the spring crops on their way into the mountains, and help villagers harvest on the way out. Decades of conflict disrupted those patterns. People no longer knew each other and were now heavily armed. Conflict resolution became a core component of the PEACE project.

Desta was hired to introduce PARIMA’s pastoral risk management model to the PEACE project. He trained herders and stakeholders on using collective action groups to build human capacity, livelihood diversification, and locally manage financial institutions. Ultimately, more than 2,000 Kuchi leaders were trained in conflict management techniques and about 3,400 conflicts along five migration routes were resolved. Invariably, the sons of these leaders learn these skills from their fathers, Schloeder says. “The beauty of this type of program is once you have the skillset you can’t ever remove it from a person.”

More than 2,000 Kuchi herders were trained in conflict management during the PEACE project where Michael Jacobs served as chief of party. Photo courtesy of Catherine Schloeder.

Building resilience

In August, Schloeder and Jacobs were back home in Montana reflecting on their careers before heading to Ethiopia for the final leg of their latest project, a $70 million USAID-funded project led by Mercy Corps. When asked what good development looks like, Schloeder doesn’t miss a beat: it’s sustainable. “We are there ultimately to replace ourselves with people who are successful.” She and Jacobs stress that good development is never about you—it’s about the people you are there for. “We are not the people with capes that come in and fix the problem,” Jacobs says. “In the end you hope that’s what you do, but if you don’t include them, you’ll never accomplish anything. You won’t find those sustainable solutions.”

And that’s exactly what they are working to create with Ethiopian livestock producers in the Pastoralist Areas Resilience Improvement and Market Expansion (PRIME) project where Jacobs serves as chief of party. The project has already affected 275,000 households and received multiple extensions due to severe drought.

“These people are used to drought. They are used to dry periods,” Jacobs says. “What has happened is the drought cycles seem to be coming closer together. And perhaps more alarming, is the fact that predictable long and short rainy seasons are not so predictable anymore.”

But the biggest issue for livestock producers, Jacobs says, is development along the major rivers has curbed their access to critical dry season grazing. One focus of PRIME is to build household resiliency after drought in new ways.

For instance, PRIME seeks to cut out middlemen. Livestock producers haven’t been getting a fair price for their animals forever, really, Jacobs says. PRIME links producers to the livestock and dairy markets and improves their access to good veterinary medicine, forage during dry seasons, and to milk processing facilities, Jacobs says. “They can have a huge amount of increase in their annual incomes just by very minor things like that.” Boosting income potential also involves connecting pastoralists with loans and microfinancing. And half of the project is devoted to transitioning people out of pastoralism—something that has been happening for decades as the population increases and available rangeland doesn’t.

Desta, Jacobs, and Schloeder are key players in more than half a billion dollars of economic investment to improve resilience among pastoralists in Ethiopia. Photo courtesy of Schloeder.

“Resilience is a big word these days,” Jacobs says. “The way I see it you have two pieces to it. You have got your individual capacities that have to be there, but then the systems also have to be strengthened, because those are the systems that people rely on to be resilient.” Literacy and numeracy are critical for individual households, but they are not enough to handle a shock such as drought, he says. “They also have to have systems in place that you and I rely on every day and don’t even think about anymore because they are always available—transportation systems, power grid systems, education systems.”

Desta, Jacobs, and Schloeder are key players in the implementation of over half a billion dollars of investments in rural Ethiopia, Coppock says. “This is a legacy Utah State can be proud of.”

With much of their professional careers lived on the road, Schloeder and Jacobs have gotten a bird’s eye view of humanity—and it’s not bad.

“Everybody has the same aspirations,” Schloeder says. “We want a roof over our head, we want good food, we want to have healthy families. We want to laugh, enjoy life. We want our children to go to school and be successful. We don’t want to have one event bring us to our knees. We are just all the same. And really, we don’t want conflict.”

By Kristen Munson